For many folks, the engine aboard their boat is a mystery and what happens inside can be closely compared to magic. You hit the start button or turn the key, and the engine fires right up! At least, you hope it does.

While there are many components working together in a diesel engine, the engine’s internal operation is a fairly basic concept. It is an iron block equipped with pistons sliding up and down that create and harness an explosion, which is then converted into a type of energy or “work” that we can use — rotational energy that can spin a wheel or propeller, for example. While this article won’t be long enough to explain every aspect, I will be diving into one of the three main things every diesel needs in order to run: air, compression, and fuel.

Compression is one of the most important things a diesel engine needs in order to create the explosion inside the cylinder. Since we are talking primarily about diesel engines in recreational boats, compression is extremely important since diesel fuel will not ignite without good compression. This is not as critical in a gasoline engine, as gasoline is far more volatile and can ignite much more easily thanks to a spark from a spark plug. Diesel engines only use the heat built up from compressing air molecules within the cylinder to ignite the fuel itself. Any reduction in that compression can prevent the ignition of the diesel and prevent the engine from starting.

So why do sailors and cruisers care about this? Well, many of us have engines that rely solely on compression to get started, meaning they do not have glow plugs, an intake grid heater, or any other form of heat to help them start, especially on cold days. The widely used Yanmar GM series (2GM20F, etc.) are examples of engines that can become extremely cantankerous in the cold when trying to get it started, because they have a lot of work to do to warm up that cold iron engine block. If there is any lack of compression, you will notice it with these engines as they will not start easily until they build up enough heat from the compression to fire. An engine like this will have a much higher compression ratio than its counterpart with glow plugs installed (Universal, Beta, etc). A compression ratio describes the amount that the air/fuel mixture in a cylinder is compressed from its original volume, with a higher ratio meaning the mix is compressed into a smaller volume, thus yielding greater power and efficiency. If you’ve ever tried to start a Universal engine with faulty glow plugs, it just doesn’t want to happen as its compression ratio isn’t enough to build up heat quickly. In an older non-glow-plug-equipped Yanmar, you may notice it gets harder and harder to start the more wear and tear it has; this is a direct sign that somewhere, compression isn’t quite where it should be. The most common causes of this type of compression issue are leaking exhaust or intake valves, or piston rings.

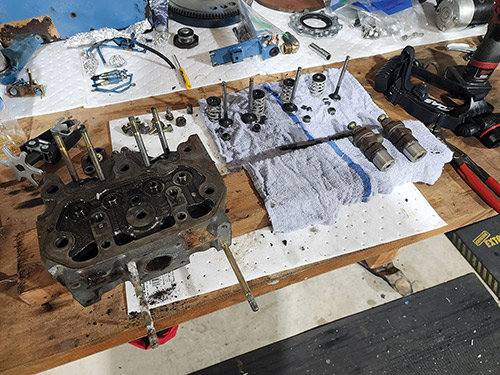

If the engine is hard to start, how do we confirm compression is the issue? I recommend a great DIY approach to finding out if compression pressure is leaking from the top of the cylinder. To do this check, while the engine is running, I will remove the oil cap usually on top of the valve cover. Because the crankcase pressure below the pistons should be “atmospheric” pressure (about 14.7psi), I shouldn’t feel any puffing against my hand out of the oil fill hole. If I do feel puffing, that tells me there is compression leakage somewhere into the crankcase below the cylinders. If I want to find out whether the piston rings are leaking or whether the top end is the culprit, I can remove the dipstick and use my hand or a piece of paper towel to indicate whether there is pressure in the bottom end. If I only feel pressure under the valve cover, most likely it is something related to valves in the top end. To be clear, this is not a comprehensive test. To get accurate numbers for each cylinder, mechanics will use a compression gauge with an adaptor that fits the engine by use of a glow plug hole or an injector hole. If they want to go further, a leak down test would confirm where the leak is coming from — in this test, compressed air is applied to the compression test adapter and one listens to the sound of air escaping.

Most of the time when diagnosing an engine for poor compression, there are many signs that indicate an issue far before I crack the gauges out. Typically, I’m led right to the exhaust and intake valves, as most recreational diesels have wet exhausts and the salty air will corrode valve seats and make the engine quite difficult to start. Recreational diesels also suffer from excess idling or low speed operation without load, and have resulting piston damage over time from soot and carbon, which are extremely abrasive to the cylinder walls. Running your engine in the recommended operating range of about 80% under load will help prevent this buildup.

A compression test, while useful, will not give us all the answers, but it can confirm whether there is an issue related to poor compression or not. And the words “compression issue” don’t have to strike fear in the heart of every cruiser. The more you know, the more you’ll be able to work to prevent these issues!

Meredith Anderson is the owner of Meredith’s Marine Services, where she operates a mobile mechanic service and teaches hands-on marine diesel classes to groups and in private classes aboard clients’ own vessels.