In our latest Throwback Thursday, ride along with an experienced rower who learns some valuable lessons about fog and current while crossing Rosario Strait.

Gray clouds covered the August sky above Washington Park in Anacortes. I tossed an inflatable life vest into my skiff, paused, and threw in a foam vest for good measure. The low-profile vest was less bulky to row in, but the foam vest didn’t need to inflate and had a measure of insulation. I put a beat-up cooler in the stern, a VHF radio at hand’s reach and, next to my seat, a small waterproof case with my personal locator beacon in it.

The beamy 16.5 foot Gig Harbor Boat Works Jersey Skiff had plenty of room, and I had food for a day and a half. I was good for two days, if I counted the meal I would get after my 13-mile row to Buck Bay Oyster Company where I was giving a presentation about the San Juan Islands rum-running history to a high-end cycling tour.

Wind whipped up whitecaps out in Rosario Strait. It was my fifth crossing in the last week, and perhaps my 40th crossing overall. The skiff handled it with its usual confidence. I arrived a little over three hours later with enough time to take a nap on a beach before my talk. The presentation went off without a hitch and I pulled out of Buck Bay in the dark. Bioluminescence popped like a green flame with each stroke of the oar. I considered rowing back that evening to enjoy the show, but decided to tie up to a mooring ball and sleep.

I woke before dawn. Stars were still out, but my oars no longer lit up the water on the steady row to Thatcher Pass, the channel between Blakely and Decatur. Here the clear blue skies over Lopez Sound gave way to a wall of fog.

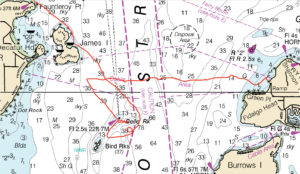

I checked AIS and gave a long listen for distant engines. Then, satisfied I was clear, I sprinted the shortest distance between the two islands across the ferry route from the south edge of Blakely to the north side of Decatur and felt my way along its northern shoreline before spotting the edge of James Island. Some fishermen were out. They were moving cautiously.

The fog was foreboding, but I did not want to give it superstitious powers over me. I looked at the beach on James Island and considered staying there for a bit. But I had things to do and felt confident the three-mile row would take me the usual hour. The fog, dense as it was, still allowed a solid five hundred yards of visibility at the water level. Without a motor, I could hear engines very far away. I tightened my low-profile life vest, sipped some water, rechecked the AIS, and took another bearing to keep me well below the ferry lane and headed east.

James Island faded into the silent fog. Each stroke finished with a clunk, a squeal in the bronze oarlock as it shifted position, and a splash as the blade dug back into the water. Repeat. I took another bearing on the compass on my phone. I twisted my head from side to side, straining my ears on the alert for a distant engine, and then back down at my bearing. Clunk, squeal, splash. Repeat.

Then came a distant murmur. Not the throaty rumble of a motor, but the hiss of static, like a radio broadcast, or the roar of far off waves hitting the shore. But I was far from shore and it was getting louder. I looked at my compass. Still good. I knew this water well… I thought. One of last week’s crossings had been in this August fog at a similar time of day. That particular fog had obscured but not eliminated the early morning sun as a bearing. Today’s fog had dissipated the light to an even, discombobulating gray. Again, I glanced at my compass on my phone. Still good.

Off my starboard oar appeared a black and white diamond day board on a pillar of concrete perched on a minuscule pile of rocks guarded by bull kelp. My gut tightened. This familiar crossing was all of sudden not looking too familiar. I knew there was a marker around this area, but it was so far south. Was there another marker I had missed?

Water piled up a foot on one side of the immovable islet, a visible reminder of the force of the Strait of Georgia squeezing through Rosario like a hypodermic syringe. I was this far south. It had happened so fast. Twisting to starboard again, I noticed the source of the growing white noise in a maw of standing whitecaps. I picked up the pressure on the oars, driving the bow perpendicular to the current.

My skiff drew towards chaotic shark-tooth-shaped waves, like some great beast inhaling. In seconds, curling white caps emerged helter-skelter and combined and broke beneath me before taking form and threatening to leap into the boat. I pulled several strokes, planted my oar and spun the stern to an oncoming wave. It slipped under the boat. I looked down at my compass. I looked up at another wave. I only had time to watch the waves. Planting the opposite oar, I twisted the boat in the other direction. Again, it passed under the hull without incident. I swiveled. Where was the marker?

I’d lost my bearing. Ragged gray-blue walls surrounded me as I juked with the waves. I couldn’t take my hands off the oars long enough to study the GPS and compass. I could pick a direction and row, but was I going the right way? How long could I dodge these waves?

A 30-foot motor yacht emerged from the fog off my stern at 500 meters. The roar of churning water obscured its engine noise. Spray crashed against the hull, and it rolled like a toy in a bathtub off my stern. A lone man braced himself on the deck, and the craft disappeared without acknowledgment.

I didn’t have time to ponder if the boat had seen me. Lumpy waves checked the boat. I’d successfully kept waves out of the boat, but was losing confidence in doing that much longer. Was I stuck until I flipped, or did the tide change? Hadn’t the tide changed? I’d looked at the tide table half a dozen times. Would it chew me up and spit me out on the other side? Could I make it until then? I was tamping down panic, and I felt myself losing.

Then, beyond the waves, as if there was an invisible wall between worlds, appeared a patch of calm water. I turned my bow and started rowing like hell. The rolling water demanded asymmetric precision with each stroke. Slow down the port oar, speed up starboard. Lean. Pivot. Drive with the legs. Heave arms and body. Pause to let a wave roll under the hull, plant the oars and drive again. It could have been seconds, or it could have been minutes.

I broke through the waves onto a pane of water not much rougher than a millpond. The current alone seemed responsible for the waves.

Free to let go of my oars, I turned to the GPS. That marker was Belle Rock. I had never crossed south of it on any prior transits. To the south were three distant barren outcroppings on the chart — Bird Rocks.

I followed the edge of the vortex up to Belle Rock. At the base, the current coursed through the tendrils of dark brown kelp. I pulled myself over the kelp on the lee side where I watched the waves roar a few yards away while I made coffee and ate food.

With sustenance, I reevaluated my predicament. I put on my foul-weather gear and immediately started to sweat. I filled my pockets with my wallet, keys, and phone. I removed my low-profile life vest and thanked myself for also bringing the extra foam life vest with its measure of insulation. I removed the PLB and VHF radio from the waterproof case and tied them to my vest. If I found myself in the water, I might have a chance. Fed, watered, and with a feeling that the waves might have gotten smaller, I headed out again.

After a hundred yards, I retreated back to the kelp. I made another cup of coffee and noted my dwindling food, water supply, and extra battery power. The day before, I felt like I’d overpacked and was glad I did; and made a note that if I got out of this, I’d bring even more food and water.

If I could not go east, then perhaps I could fight the weakening current north and at least find myself on the solid ground of James Island. But I would still have to cope with dwindling supplies. I just needed little things — a little less fog, a little less current. So I waited, and when I felt the fog and current change, I began rowing north.

Somewhere between Belle Rock and James Island, I spotted a ship to the east — perhaps a mile away. Fildago and James remained shrouded in fog, but it was lifting. Two hours had passed since I had tried my initial attempt. I thought of my now-limited provisions and changed back to my original easterly course.

An hour later, I stepped on the beach at Washington Park. That hour was as easy as I imagined it was going to be in the first place. I was shaken, pumping with adrenaline, and felt lucky to feel chastised by the fear. I hadn’t scared myself like that in a while. My mind churned with the decisions that led to this moment. Was this just a moment of growth after rowing these waters for years, or had I been irresponsible? Would that take time to tell?

Upon reflection, I could have had a backup GPS, one not tied to my phone, and a backup compass to boot — now I do. The ubiquitous electronic tools we have in our pockets are seductive but have limitations. I had read the tide correctly, but had made mistakes equating tide with current. I read up a bit on that and downloaded an app for tides and currents.

A few weeks later I crossed Rosario in the same boat, without incident, but with this incident in my head the entire time, thankful for the lessons I can walk away with.

Jordan Hanssen

Jordan Hanssen is a writer who spends a lot of time in tiny boats. Check out his book “Rowing into the Son,” take one of his rowboat tours of Seattle, or learn more about his hijinks at www.jordanhanssen.com.