How California Boats Invaded the Salish Sea

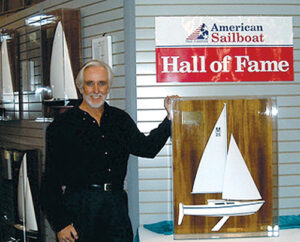

At first glance, Roger MacGregor comes across as every bit the engineer. He has a reserved, pragmatic personality focused on building things. When I met him at his home in Newport Beach, California this spring, he quickly moved the conversation from introductions and pleasantries to describing the architectural features of his house, which sits on a dock overlooking the busy harbor.

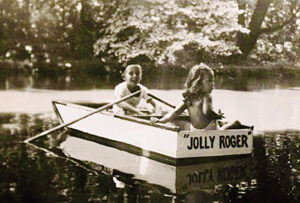

“This was a one-story building when I moved here,” he explained, pointing to the upper level he had added himself. After spending several days with Roger, I also saw an artistic, fun side that—at age 90—still gets caught up in the joy of being on the water while relishing aesthetic details. He designed the decorative stained glass that lines the railing of his wharf, for instance, and his 70-foot boat Anthem was recently named one of the “most beautiful sailboats of all time” by Sail Universe, the culmination of a career that began when he built his first vessel, Jolly Roger, at age seven. While Jolly Roger was a wooden rowboat, MacGregor recognized the potential of fiberglass early on, eventually outlasting his competition and engaging thousands of first-time boat owners.

During those sunny spring days, Newport Beach seemed a world away from my home waters in the Salish Sea. Yet MacGregor boats have a solid presence in the Pacific Northwest, extending Roger’s influence far beyond Southern California. His story provides a glimpse into an industry and lifestyle that evolved rapidly during the late twentieth century, transforming recreational sailing.

The “Flaming Nuthouse” of Competitive Boat Design

California’s South Coast, located between Los Angeles and San Diego, is as alluring as a postcard, characterized by blue-green water, golden sand, and tall palms swaying in warm breezes. Its surfing culture, borrowed from Hawaii after World War II, adds to the charm. Yet this region also became an industrial powerhouse during the post-war period, with steel mills, auto assembly plants, and shipyards. The aerospace industry flourished here in the 1940s, thanks to the availability of a skilled workforce, universities that spurred research, and land. Roger, who was born in Pennsylvania and grew up in Ohio, moved with his parents to Southern California in 1948, joining the great post-war migration of residents from the Midwest and East Coast to the Golden State. He studied economics at Occidental College, where he met his wife Mary Lou, and after several years in the Air Force entered business school at Stanford University.

Here he began the project that would become MacGregor Yachts. “We had a couple of kids by then,” Roger explained, “and we wanted a boat where we could be reasonably comfortable and wouldn’t sink… and there weren’t any.” One centerboard sailboat he considered “would fall over just looking at it.” Wooden boats were heavy and had to be moored, which could be expensive. So the goal of his business school project was to design an affordable, unsinkable, trailerable boat that a family could use. After Stanford, MacGregor worked for Ford Motor Co.’s Aeronutronic Missile and Space Division, where he was able to observe “Henry Ford’s original concept of a production line.” In 1964 he started his own boatbuilding business in Costa Mesa, up the hill from Newport Beach, while still employed at Ford. His new company’s first vessel was the West Wind, which Mary Lou, who was very much engaged in the business, described as “ugly as sin and fast as smoke.” When the number of employees reached eight, Roger left Ford, and by the mid-1960s, MacGregor Yachts was off and running.

Many of Roger’s neighbors had the same idea. Estimates claim that 70 to 100 marine companies operated in Costa Mesa, which became the center of boatbuilding in the late twentieth century (Bradley Zint, “New Exhibit Tells ‘The Hull Story’ of Costa Mesa’s Boatbuilding Past,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 2018). Sailboat companies operating along the South Coast included Catalina, Columbia, Cal, Ericson, Islander, Hobie, and others.

“It was a flaming nuthouse” of competing businesses, Roger recalled. “My street had probably 20 boatbuilders on it, and you couldn’t go anywhere without running into a truck hauling a boat or resin tanks” used to make fiberglass. They were “turning out thousands of boats. It was just unbelievable.” At lunchtime during the 1960s and 1970s, local restaurants filled with boatbuilders clutching drawings and financial plans, with “all the necessities of the industry spread all over the place.” Attracting employees was easy. “I’d put a sign out and 50 people came in,” he remembered. Keeping them was a different story, as rival companies lured workers away.

The proximity of all these businesses made the challenges of establishing a new company more immediate and more personal. “It’s one thing to compete with a company in a distant part of the country,” Roger commented. “It is quite another to compete with one across the street or just over the fence.” In the days before cyber espionage, Costa Mesa spies were low-tech, sometimes peering through fences and into the windows of rival operations. “What one company learned was captured by another in a matter of days, if not hours,” he marveled. Those who could not keep up were left behind. “It is the sailboat’s equivalent to Silicon Valley, only more concentrated.”

Listening to Roger talk about the early days in Costa Mesa reminded me of a movie from the late 1990s called “The Pirates of Silicon Valley,” about the cutthroat rivalry between Apple and Microsoft in the early days of personal computers and information technology. As “pirates,” Steve Jobs and Bill Gates brought innovation, explosive growth, and, some would say, an aggressive, fierce culture to their companies. These entrepreneurs flourished because they seized opportunities, and they were at the right place at the right time.

Building Boats in the Wild West

The competition in Costa Mesa and along the South Coast quickly fueled improvements and efficiencies. Fiberglass, for example, presented boatbuilders with exciting possibilities, and MacGregor Yachts embraced the new technology. This glass-reinforced plastic, invented in the late 1940s, encouraged aerodynamic designs and monolithic hull construction. Unlike wood, fiberglass resists rot and leaks, making it ideal for boat construction and maintenance. By the 1960s and 1970s, it had become the dominant material in boatbuilding.

“Fiberglass could create incredibly complex curved surfaces,” Roger explained, “providing the designer with complete freedom regarding styling.” Aesthetically, MacGregor preferred a modern appearance with sleek lines, asserting that “the new fiberglass boats were far better looking than the wooden boats that they replaced.” While that is a matter of endless debate, fiberglass offered an unbeatable advantage: it was affordable, allowing thousands of new boat owners to enter a market that had previously excluded them.

Another way Roger kept costs down was to implement workstations geared toward specific tasks, patterned after Ford Company assembly lines. “That was my advantage,” he explained. “Each station had all of its tools, jigs and fixtures, parts, diagrams, and samples.” In fact, he designed boats with workstations in mind, expecting that each component would be assembled independently. This approach reduced the need for skilled labor, making production more efficient and less expensive. In contrast, other companies adopted a traditional approach, with the same skilled employees handling all sections of boat construction. Catalina was an example, and MacGregor spent some time in Los Angeles with owner Frank Butler observing his production techniques, concluding that he preferred his own workstations.

Roger described Butler as an “excellent boatbuilder,” someone he respected and admired. “I would rather take on General Motors as a competitor,” he commented, than “a motivated individual entrepreneur, such as Frank Butler of Catalina or Jack Jensen of Cal Boats. With family-owned businesses, their money, egos, and pride are on the line,” driving a desire to succeed and “flatten the competition.”

Perhaps Roger saw himself in the entrepreneurs surrounding him. The social scene gave him ample opportunity to mingle with rivals, as every Friday night they met together at a local bar for “Boat Dealers’ Balls.” Emotions ran high, and these gatherings sometimes ended in brawls and fistfights. “It looked like the Wild West,” he mused, remembering the unbridled exuberance and lack of restrictions. There was camaraderie, too, as boat dealers sponsored football and baseball leagues and formed lasting friendships.

Surfers, Sailors, and Epic Parties

During the 1970s, Roger became pals with a fellow entrepreneur who shared a dream of building a company that would bring sailing to the masses: Hobart “Hobie” Laidlaw Alter. Inspired by the surfing culture at Laguna Beach, Hobie began building 9-foot balsa wood boards for his friends in the 1950s, eventually opening a surf shop in Dana Point. As a champion surfer, he helped revolutionize the surfboard industry by introducing polyurethane foam boards, which were lighter and faster than the old wooden boards. By the 1960s, his focus had shifted to catamarans patterned after Polynesian twin-hulled vessels. The introduction of the Hobie Cat 14—light, affordable, and easy to use—helped set a new sailing culture in motion. Hobie organized regattas, fostering camaraderie and competition among racers, many of whom were new to sailing. Later in his life Hobie moved to Orcas Island, but in the formative years of the 1960s and 1970s he was a legendary figure in Southern California.

“We were fairly close,” Roger recalled of his neighbor. “Hobie was kind of my idol for a long time because he got a big business started.” One of the most memorable results of their friendship was a massive gathering of employees from Hobie’s company and MacGregor Yachts on the beach at Crystal Cove. Nearly 500 people attended the party, which included music blasting from a sound system on the bluff overlooking the sea, while participants roasted pigs in the sand. Caught up in the revelry, some of the employees fought over the food, eventually toppling the sound truck and sending it crashing to the beach below. “What a day,” Roger commented, remembering the arrival of the authorities who warned him, “you gotta stop this craziness.” Roger and Hobie were ordered to clean up the beach. “It was epic,” Roger concluded.

After talking with Roger, I visited Crystal Cove, now a state park, and tried to imagine the wild scene decades earlier. All I saw were quiet couples walking on a lovely beach, with pelicans soaring overhead and a few terns and seagulls running along the sand. It was a different era.

Meanwhile, in the Salish Sea

MacGregor Yachts sold close to 50,000 boats, including catamarans, 65- and 70-foot racing yachts, and sailboats ranging from 19 to 26 feet. Roger attributes much of his success to boat dealers who helped with transporting, outfitting, and sales. He had dealers all over the world, but none sold more boats than Todd and Cheryl McChesney of Blue Water Yachts in Seattle.

Cheryl bought a MacGregor Sailboat in the late 1980s after seeing an ad in 48° North. While she had grown up boating in the Salish Sea with her family, this was the first vessel she had purchased. “Hey, I can get a boat,” she realized when she saw the price. “And I could trailer it, too,” eliminating the need for moorage. She later married Todd, who had sold her the boat.

Together, the couple devoted the next three decades to introducing many first-time buyers to the joys of boating. Cheryl guessed that as many as 75 percent of their customers were new to sailing, while the “rest were experienced sailors who were downsizing for easier handling or to trailer to lakes and farther destinations.”

Blue Water Yachts brought nearly 1,000 MacGregor sailboats to Pacific Northwest waters. “It’s the perfect boat for this location,” Cheryl explained. “With the distances you can cover under motor, you can actually get to places you couldn’t before.” And while many are content to explore the protected waters of the Salish Sea, some MacGregors have circumnavigated Vancouver Island and ventured to Alaska.

The McChesneys offered sailing lessons to all customers who wanted them. “We made the boats easy to sail from the cockpit,” Cheryl commented, and “we had the best instructor, Ray Copin, retired USCG Captain and aviator, who was himself a MacGregor owner.”

From the outset, the couple organized gatherings, including concerts, barbecues, and seminars, where MacGregor owners could socialize and learn more about their boats. Their annual MacGregor Rendezvous grew out of a Friday Harbor event they co-sponsored in the early 1990s with 48° North, called the “Plastic Fantastic Fiberglass Boat Festival,” a spoof on the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival. “There were lots of MacGregors there,” Cheryl remembered. “We made a grand entrance sailing together past the ferry dock to join the festival.” Today, the MacGregor Yacht Club of British Columbia continues the tradition of providing an annual rendezvous and an online space where owners can share cruising and maintenance tips.

By the early 2000s, most of the boat builders along the South Coast of California had closed shop or relocated. Environmental regulations, rising property values, and encroaching population increased the costs of operating in Costa Mesa, fragmenting the concentration of businesses that had spurred the innovation and productivity of the past. MacGregor operated longer than many of his competitors, stopping production in 2014 when a retirement home emerged on the border of his plant. Although awareness of the toxicity of resin fumes was not widespread in the 1960s, by 2014 the business and regulatory environments had changed.

Legacy

Blue Water Yachts continues to ship MacGregor parts to boat owners all over the world, a testament to how widespread MacGregor sailboats remain. Cheryl marvels at the far-flung destinations she never expected to find boats, wondering, “Really, they have water there?” Todd reports that the most remote location for a MacGregor sailboat may be Spitsbergen Island in the Svalbard Archipelago, about 600 miles north of the Arctic Circle, where he recently shipped a cockpit enclosure. He joked that the added protection would extend the owner’s sailing season “from three to six weeks.”

“Should we go sailing?” Roger asked on our last day together. Off we went to board Anthem, the second version of his “most beautiful” 70-foot boat. The breezy, sunny day in March could have passed for summer in Seattle. We backed away from the dock to enter a bustling harbor, weaving through a fleet of electric Duffy boats, various crews, power vessels of all sizes and shapes, and a few sailboats. We raised two of the five sails while still in the harbor. As our boat shot forward and heeled 20 degrees, I nervously glanced at the boats all around us. But as soon as we sailed out of the harbor on a reach, Anthem easily hit her stride and I relaxed, realizing that not only had Roger designed and built the boat, he had won the Newport Ensenada Race three times. We were in the best hands, and I sat mesmerized as we sped down the coast. Roger looked as content as I had seen him, clearly in his element. And I thought this is what it’s all about—getting people on the water, sharing the greatest sport and lifestyle the West Coast has to offer.

Oh, The Places We’ve Gone!

What Frank and Lisa love about their MacGregor 26x

Vancouver Island’s Cape Scott is not a patch of water to be trifled with. Days of gales gave way to light breeze and sunny skies and we bounced along under sail, equal parts exhilarated and terrified. Suddenly, a dark shape surfaced off the starboard bow. A humpback! Practically eye-to-eye, we stood dumbstruck by the sublimity of the scene, watching its tail flukes disappear beneath the waves. That evening, we anchored in Quatsino Sound, not a soul around for miles. Otherworldly howls came from shore—the wolves several cruisers reported in the area. We pulled up another full crab pot, and couldn’t think of a place we’d rather be.

This was one of the most memorable journeys Frank and I have taken in Murrelet, our MacGregor 26x. Living in Seattle, we had only two weeks of vacation and could not afford to charter a boat. How did we pull this off? We trailered our boat to Port Hardy and took out a few days later at Coal Harbour. Conventional sailboats in Seattle traveled for weeks to reach the same destination.

Trailering a 26-foot boat is not for the faint-hearted, it’s a different skill set from sailing. Yet our boat’s trailerability has provided access to many cruising grounds we otherwise could not explore. And our 50-hp outboard allows speeds up to 20 knots, depending on the weight in the boat and whether the water ballast tanks are full.

Frank and I named Murrelet after a Northwest seabird, which, despite its small chunky body, is a fast flier, often seen streaking across the water. Murrelets nest on land, sometimes miles inland, reminding us of a trailerable MacGregor. We have devoted many hours searching for wildlife in our boat, often bringing friends and Audubon Society members along. Our retractable centerboard allows us to venture into shallow areas. Sure, we could do this in kayaks, but our MacGregor gets us and our guests home before dark.

Lisa Mighetto and her husband Frank have sailed the Salish Sea in Murrelet, their MacGregor 26X, for 25 years, including a trip to the west side of Vancouver Island. She is grateful to Roger and Mary Lou MacGregor, Todd and Cheryl McChesney, and the Costa Mesa Historical Society for information and photos.