This article originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of 48° North.

If you’re reading this article hoping to discover the next great cruising destination, you should stop right here. Especially if you rate your itinerary like most guidebooks (swanky places to visit, inspired restaurants, easy access to laundry, artisanal cheeseries) your subconscious already knows why you’ve never cruised Hood Canal: It’s a long way from everywhere, it’s on the way to nowhere, and there’s almost nothing there — and I mean that in the best way.

For a lot of boaters, nothing is an issue. No shame. Plenty of folks avoid destinations with nowhere to stop, nothing to do, no boutique brewery/distillery/restaurant/charming shop owned by Seattle/Bay Area/Big Tech transplants who decided to cash it all in and splash their hobby business all over their Insta feeds and #livetheirbestlife. Hood Canal seems to have none of that, and for me, that’s the point. It’s the undisturbed nothing of the place that makes it worth going to, especially in February.

One mid-February weekend, my family and I borrowed the 32-foot custom wooden M/V Kloshie Bay and decided to make a weekend of it. Rather than facing a gale in the Strait, or the COVID threat of you monsters in King County, Hood Canal looked like our ticket. We were looking for nature we’d never found, and we found it. Sort of.

Hood Canal — What did we know? What did we care?

Hood Canal — What did we know? What did we care?

We had two days, fuel to spare, and a boat with the amenities that felt like Spartan opulence compared to our years of open-boat camp cruising: a head that wasn’t a bucket, a roof that wasn’t a tent, bunks that weren’t Thermarests, a diesel heater. We couldn’t figure out the fridge, but whatever — the weather was cold enough that, even without ice, our topsides cooler worked just fine. We were living large. We fired up, took in the fenders, and kept turning right until we were under the floating bridge that spans what feels like the moat between urban insanity and the prospect of simpler times.

Entering Hood Canal is technically simple. There is current, but it tops out most days at a knot or so and it’s not too swirly. It’s either with you or against you depending on the flow and your direction. Wind patterns seem to be the same binary north or south of Puget Sound. There’s a bridge to contend with, but fixed height transits to the east and west means there’s no need to ask for an opening if your boat tops out at less than 55-feet. Luckily, you still can open the bridge if you’re feeling tall and/or spiteful enough to cause a traffic jam. The bridgetender answers on Channel 13.

Back to the nothing: By now, I’m sure the combined force of the Kitsap, Mason, and Jefferson County Chambers of Commerce are midway through rotary phone dialing in a complaint to the 48° North Editorial Board. To them, I offer a combination of “Look in the mirror and get used to it” and a sincere promise that I’m not slagging them.

Saying Hood Canal has nothing to offer boaters isn’t fair. It’s like hating a National Forest because it has shitty WiFi. Actually, it’s exactly that. The Canal’s western shore is bordered by a thin band of human habitation and then a montage of federally controlled timber, recreation, and park lands; which means the views are incredible. Fifteen miles south of the bridge, just past the attentive patrols of the Bangor submarine base, the Toandos Peninsula fades away and unmitigated panoramas of snow capped Olympic Mountains plunge straight into water containing the abundant sea life that makes the canal famous for its shellfish production and recreational spot prawn opener. If you close your left eye, it’s like being in Alaska. I’ve spent the last few years in and around Ketchikan for the Race to Alaska, and the mountains, isolation, and nature per capita of the west half of Hood Canal were like a methadone fix for the two years of cancelled races. Not the same, but it stopped the shakes for a while.

If Half-laska is Hood Canal’s west coast, it’s eastern shore is Bremerton’s low rambling rural backside; the Kitsap Peninsula that seems suspended somewhere in the time triangle bounded by the enlisted Navy/Twin Peaks/“My cousin’s on meth” vibe of recent decades, the 1860s logging boomtimes heralded by Seabeck’s lone heritage marker, and whatever nervous small talk the last lost tourist made until they worked up the nerve to ask the locals the fastest way to get their Subaru back to the ferry. Any ferry.

Both sides of the canal have an impressive resiliency of character. They are who they are, which isn’t nothing in these times of cultural amalgamation.

Since the time of first European contact, the cute and accessible parts of the northwest have been colonized and made generally less cool by the successive waves of people from elsewhere cashing in and reinvesting. Look at South Lake Union, Bellingham, the Methow Valley, Tacoma… all fancier and sometimes unrecognizable from their grittier former selves. Despite their best efforts, the banalification of Hood Canal’s communities has been largely unsuccessful. Hood Canal is getting fancier but it’s happening mercifully slowly…or alternately painfully slowly if you need much more than 68 miles of one way waterway.

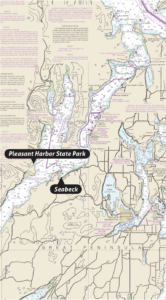

We checked the fuel gauge, motored deeper into the Half-laskan fjord and looked for anywhere to stay. The entire northern half of Hood Canal’s bold shoreline offers essentially two choices. We went to both before settling and can report with authority that, for alternate reasons, both were pleasantly underwhelming.

#1- Pleasant Harbor State Park: A picnic bench with moorage

#1- Pleasant Harbor State Park: A picnic bench with moorage

Because I’m cheap, we started at Pleasant Harbor hoping to poach moorage in the state park’s understaffed offseason. The harbor’s narrow entrance is complete with a full pucker, visible bottom shallow spot that will have you wracking your brain to remember exactly how high up the hull your transducer is. Once past that, it’s a hard right to one of the most protected dockside moorage options I’ve ever experienced. Located in a closed bay that protects from the east/west/south, the state park dock is tucked behind a middenlike spit that offers protection to the north. Absolutely bombproof.

Upland, the postage stamp of a park is mostly a parking lot, but boasts a single picnic table, a vault toilet, a narrow slippery beach that disappears at high tide, and a perimeter of warning signs that range from neighborly “No Trespassing” to the successfully frightening “Eat Shellfish and Die” biotoxin warnings. Fans of close passing logging trucks at highway speeds will enjoy the hiking trail that doubles as US 101. As summarized by our 5-year-old: “They call it a state park, but it’s really a trick state park.” Look at the words on her.

If you need a place to tie up overnight and never leave your boat, Pleasant Harbor State Park is the place for you and maybe four other boats. Full stop.

Nearby there are more options. Further into the bay there is a full service marina (www.pleasantharbormarina.com ) that has transient moorage, a fuel dock, a restaurant, the whole nine yards — probably even WiFi at speeds that won’t spark rage. A short two-mile walk down the highway towards Brinnon is one of my favorite bars of all time (The Geoduck, god bless it.)

Weighing our options, the combo of COVID-based restaurant avoidance, a 5-year-old who has yet to get a fake ID, and our hope for a hike that didn’t involve choosing between the ditch and oncoming traffic, we cast off to seek our fortunes on Kitsap’s golden shores.

#2- Seabeck: PNW AF

Landing in Seabeck was like travelling back in time. Not as far back as the 1860 logging camp heyday. Maybe closer to the 1980s — roughly the last time we all thought Seattle was going to hell.

Back then, the Seattle PI’s populist curmudgeon, Emmet Watson, wrote about “Lesser Seattle”; the vanishing character of a blue collar city, the fading echoes of World’s Fair optimism, “the Seattle that still smelled like clam juice” that was getting Californicated and developed out of existence.

The mid-80s version of the fight for our regional soul seems almost adorable by today’s standards. But visiting Seabeck was like dropping back into a Washington that still had an accessible kind of rugged — when getting a bigger boat was upgrading to the Skagit 24, when coffee came in cans and the standard rain gear was a deeper scowl and a thicker sweatshirt.

I’ve lived in Washington my whole life and, in Seabeck, part of me felt like I was coming home.

Emotional homecoming aside, arriving in Seabeck actually was more like the time I came home and they changed the locks. Tieing up, we headed up to pay at what we assumed was the moorage office. The head scratcher du jour was the gate at the top of the dock that was locked. Yes, from the outside, but also from the inside. We were locked in and stranded in a mostly vacant marina. After a too-late-to-matter, 3G-paced read of the marina webpage, we learned that the reason for the locked gate was the same reason that there is no moorage office: Seabeck has no transient moorage.

Yes, we left a state park because there was nothing to do and nowhere to go, only to arrive somewhere where we were imprisoned and trespassing. No, the irony was not lost on me.

I called the number on the sign, left a message, and shuffled back aboard resigned to a weird night on a lonely boat, endless kid’s books and games of Go Fish, all within sight of the bright lights of Seabeck. That’s when Gretchen called me back.

Gretchen owns the marina and, as such, could have said many things. Rather than tell the jackass on the phone who didn’t read the whole website exactly where he could go, she told us to just stay put and gave us the gate code; because there was nothing but space, we’re all humans, and… of course.

Gretchen’s call was the rare kind of customer service you get when the person on the other end of the call isn’t deep inside a Mumbai call center, but the actual owner, down the road and calling from her actual cell phone. More than that, it wasn’t the well-honed, customer “abattoir with a smile” that we’ve pioneered here through the legacy of Nordstrom’s/Starbucks/Amazon that is less about the customer needs and more a well calibrated strategy of how to fleece you and make it feel good. This wasn’t that, this was a throwback to a time when people talked to people. Emmet Watson would be proud. I punched in the four digits and opened the gate with a renewed sense that Seabeck might be the shining exemplar for us all.

While I was blinded by the grandeur of a place whose certain destiny is to save us from ourselves, from a strict accounting, Seabeck is four buildings and a gravel parking strip wide and boasts a compliment of businesses that run the gamut: small espresso stand, general store, curated doodad emporium, and a *headscratch* art gallery.

The general store sells the beef jerky/chips/half-rack-of-Busch kind of staples you need if your diet was designed for cheat days and kidney stones. There’s basic hardware, DVD rentals, booze, freezer case ice cream, legitimately cool souvenirs, and some 2020 election swag still rubbing its hands for the liberal tears that never came. They also sell bait.

The ever burning woodstove in the corner serves as the community center, or so the longtime resident behind the counter told me. “People just come in, get warm, and see what’s going on.” I didn’t see this, but it felt like the kind of place where locals roll dice with the staff to see who pays for coffee.

The 5-year-old’s favorite store was the well curated knick-nackery next door. It was tiny, not much more than a closet with a street front, but it was filled with a mix of new merchandise and interesting finds that felt high graded from a lifetime of successful rummaging. Most importantly, it had a kids book about Egypt. We bought that.

While the General Store was the unofficial town hall, and the doodad store won the youth vote, the crown jewel of the Greater Seabeck Commercial Area is Seabeck Pizza, the original and still flagship of what has burgeoned into a six store chain that dots the length and girth of the Kitsap Peninsula. Seabeck was their first location and even before we ordered I knew it was their best. Call it instinct, call it the undeniable beacon of awesome that lights the sky whenever your delivery vehicle is an almost rusty ’69 Ford Ranchero, call it the fact that they have a boat that will deliver you pizza up and down either side of the Hood Canal (bonus points: it’s a Skagit 24.) Of course we ordered.

I’m not sure that the Northwest has a regional pizza tradition that is defined and recognized, but if we did, Seabeck might be tied with Seattle’s Northlake Tavern as our Kardashian level trendsetter. Seabeck Pizza flexes hard with its quintessential PNW pie; a pizza built on a “more is more” philosophy that feels gloriously and unselfconsciously uninformed by any Italian tradition that wasn’t pronounced with a hard “I”. The crust was deep, the quantity of cheese felt like a dare — a dare that was specifically designed to hide the bounty of toppings under a thick veil of lactose secrecy, not because it was embarrassed of what was under there. This was Seabeck Pizza. It demanded your trust two bites before it earned it. Respect.

Dine-in wasn’t an option, so we took our greasy box down the empty dock and ate onboard. There wasn’t a cannon shot at sunset, no cinnamon roll delivery at breakfast. In the morning, we oatmealed in a gray drizzle, then cast off our lines and steamed north and homeward. Seabeck cared enough about us to let us leave in modest anonymity.

So closed our Hood Canal adventure. Would we do it again? Hard maybe. Either way, it was worth it to restore my faith in this PNW we call home and the people who live here. Data point of one, but I say this: head to Hood Canal, anchor off of Seabeck, eat the pizza, embrace the nothing, and reconnect with the Washington of yore. If you pay attention, you can still smell the clam juice.