The Anacortes-based crew of the custom Perry-designed 48-foot sailboat, One Ocean, is now several months into their expedition to circumnavigate the “One Island” of North and South America. They are led by Captain Mark Schrader and Project Director (and author of this article) Jennifer Dalton. All along the way, the voyage balances research and education—with several scientists aboard who are working with professional researchers ashore to gather data that helps better illuminate ocean health and challenges. The crew then actively shares this info as well as stories of their adventures, connecting and educating communities and students far and wide. What follows is an excellent sea story about their passage across the Bering Sea enroute to the Northwest passage. Learn more at: www.oneislandoneocean.com.

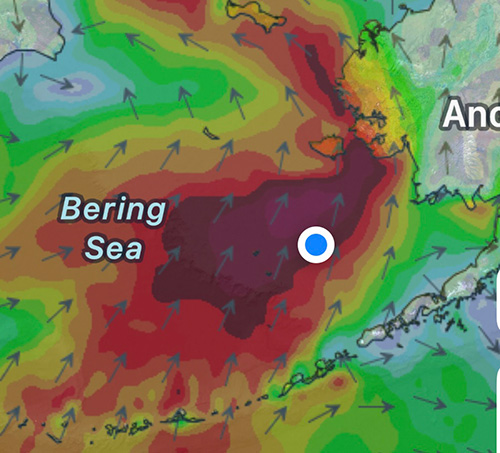

Mark and I were on the 6 a.m. watch. I hadn’t slept much. The gale-force storm we’d been tracking had arrived. From my bunk, I listened as the waves intensified, crashing violently against the hull. On this tack, my bunk was on the high side and my body was held in place by a lee cloth. Though monitored closely using Windy and Ventusky, the realities of a storm always unfold with some unique personality, and this one was increasing in strength at a time that coincided with my upcoming watch.

I climbed out of bed with the ease of a drunken sailor, the boat tossing me around the cabin as it rode the waves. In the main saloon, sailor/scientist Mike and Outreach Director Tess were alert and focused, wrapping up their 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. watch. They briefed Mark and me on the conditions. Mike referred to the 25-knot winds as “sporty.” They’d already reefed the headsail before the wind picked up, and the main and mizzen sails were both double-reefed. One Ocean was ready, thanks to my crewmates.

Mike and Tess retreated to their bunks, and I began making our morning coffee. That’s when the autopilot was suddenly overpowered by wind and waves. The boat spun up into the swell, and instantaneously the view through the windows turned white—a massive wave had engulfed us, pounding and churning us out of control. One Ocean has two helm stations—one inside the pilothouse and the other in the cockpit—and Mark tried to reset the autopilot from the protected pilothouse helm, but it wouldn’t hold.

Mark stayed at the inside helm while I clipped my harness to the dodger and climbed into the cockpit to take over the more responsive outside helm. As I got One Ocean back under control, huge waves crashed into the cockpit through the open sides of our dodger enclosure and, combined with sideways rain, I was soaked in seconds. It was only 41 degrees outside, and the Bering Sea water temperature was just 39 degrees—confirmed by the Applied Physics Lab’s data monitor. I was woefully underdressed: fleece sweater, salopettes, rain boots and life jacket—nothing more. The waves towered 18–20 feet, and I could hear each one roaring up behind me.

Mark soon came out in full foul weather gear to relieve me so I could suit up properly. My hands were frozen, my entire back sodden. I handed over the helm just as One Ocean caught a wave and surfed down it, white foam breaking all around. Mark turned to me and said, “Next time we decide to save the planet, we fly.”

For the next six hours, we traded shifts at the helm until calmer conditions would allow us to employ the autopilot once again.

I had been intimidated by the Bering Sea, and I suppose I was right to be. Before leaving Dutch Harbor, the crew, like always, reviewed multiple forecasts. We compared at least three different weather models across various apps. Two showed the storm missing us; one predicted we’d ride a strong 20 to 25 knot southerly.

We decided to go, but not without preparation. I followed Mark as he inspected every inch of One Ocean. His eye for detail, for safety, and for crew comfort came from years of experience. I trusted that. Still, I was respectfully nervous. I pulled him aside after our meeting and asked quietly, “Are we sure this is a good idea?” The Bering Sea was unknown territory for me.

He listened. We triple-checked weather models, added a second reef in both the main and mizzen before our departure (both of which we happily utilized mid-gale), and ensured everything was lashed down. He felt confident in the boat, the crew, and our preparation.

When we left Dutch Harbor, the sun was shining. The sea was calm. The Bering Sea felt less intimidating than I’d expected. That day of sailing in fair conditions helped. Whatever my wavering emotions before the crossing, when I took the helm during the gale, I wasn’t afraid. I felt steady. I felt ready.

Mark had been training me for a moment like this. Over the past few years, I’ve been an eager student, learning from this Jedi-master of sailing. I was grateful he was there, but also proud that my instincts, preparation, and training were solid. I was relying on those skills more than I was relying on him. When he returned to the cockpit, layered up and warm, I was grinning. He laughed, pulled out his phone, and took a video. “You’re a natural,” he said.

I grew up sailing and windsurfing. Out there, in that wild storm on the Bering Sea, it came back to me. I could feel the waves through my feet, anticipate the swell, and surf the boat with confidence. I was in my element. I wasn’t just keeping control, I was sailing this amazing boat in epic conditions across one of the world’s most beautifully remote and rugged patches of water.

Mark said I handled it exceptionally well. Coming from him, that meant everything.

I’ve always felt connected to One Ocean, but now, I feel bonded to her on another level. I know I still have so much to learn—any sailor does. Every moment at sea brings new lessons. Mark has taught me so much, and some days it’s overwhelming, but I’m grateful for every bit of it.

We’ve only just begun our 27,000 nautical mile journey, and already we’ve faced serious crossings. As we head farther north, the next challenge awaits: navigating ice. And lucky for me, I know just the guy who can teach me about that too.

Jennifer Dalton is the Project Director and crew for the Around the Americas sailing and research expedition that departed Anacortes, Washington in May 2025. The expedition is conducting the first ever pole-to-pole bull and giant kelp study and sharing findings through an open online education platform. www.oneislandoneocean.com