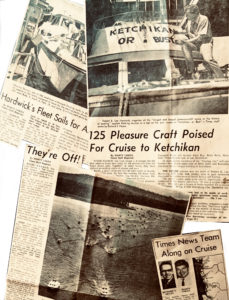

Radio personality organizes a motley armada of 125 powerboats, hoping they can make it from Puget Sound to Alaska — What could go wrong?

This article was originally published in the February 2022 issue of 48° North.

The year was 1968, and it was time for something nice to happen. We’d just lived through the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. Vietnam War protests raged, and the country had earlier experienced other dark symbols of the 1960s. Throughout the tumultuous period, I was a young general-assignment reporter at The Seattle Times, covering everything that came along… from war protests and serial killers to ospreys nesting on high-rise ledges.

When you were on general assignment, you never knew what you’d be covering each day. So I developed a strategy of inventing positive features I could suggest to my bosses, like climbing Mount Rainier on the 100th anniversary of the first known ascent, or being a Salvation Army bell-ringer to tell the story of how donations help those in need. Or even driving a little three-wheeled ice-cream truck on a summer day, delighting kids in a suburban neighborhood.

Catching wind in early 1968 of a planned small-boat cruise from Puget Sound to Ketchikan, Alaska, that was invented and promoted by radio personality Robert Hardwick, I knew — as a guy who’d spent his whole young life aboard boats — that this was a story I had to cover.

Hardwick was a seasoned boater, and his boondoggle was billed not-so-modestly as “The Largest and Longest Pleasure-Craft Cruise in the History of Boating.” He envisioned a mix of 125 small cruising powerboats parading together from Puget Sound to Southeast Alaska. The plan was to depart Roche Harbor and make 100 nautical miles per day, happily clustering for overnight stops in Campbell River, Alert Bay, Bella Bella, Butedale, and Prince Rupert before reaching Ketchikan, where they’d rest for a while and then return south via a similar route. Never mind that docking 125 boats overnight in Bella Bella or Butedale might present a few challenges, since the locations lacked dock space for more than maybe a dozen visitors.

Soon after hearing about Hardwick’s zany plan, I pitched the story to The Seattle Times’ managing editor, suggesting that the paper dispatch a reporter and photographer — that would be me and anyone they chose to shoot photos — to ride along with the armada of small-boat skippers, hoping to file daily reports from along the route. Knowing that conservative “Fairview Fanny” — a nickname for The Times back then — was not inclined to celebrate self-serving disk-jockey stunts, I tried to convince my boss that a huge, motley fleet of strangers, with all levels of experience and aboard boats of mixed pedigree, might produce some actual (maybe even bad) news, or at least enough weirdness to make it interesting. He raised substantial eyebrows throughout my pitch, but grudgingly agreed. My good friend Dick Heyza, a Times photographer I’d teamed with on many earlier stories, was chosen, so we quickly packed duffle bags and gear.

On July 19, the day cruising boats were scheduled to rendezvous at the starting line, almost all of the 125 registered boats assembled in Roche Harbor. Some, we learned later, couldn’t find that corner of San Juan Island… not a promising sign. Walking the docks that afternoon, we realized the cruise would include a crazy variety of boats and skippers — some little 16-foot outboard runabouts with gas-station roadmaps for navigation, on up to an ancient 65-foot retired tugboat that would soon tow many of the smaller vessels after they’d either broken down, run out of fuel, hit logs, or otherwise been unable to reach the day’s destination. Aboard the boats were 450 souls — solo adventurers in some of the smaller boats, entire families and some of their friends in larger cruising vessels. Serious skippers, rowdy kids, heavy-drinking guests along for a 1,400-mile party, newbie boaters with zero experience. They were all there…ready or not.

On July 19, the day cruising boats were scheduled to rendezvous at the starting line, almost all of the 125 registered boats assembled in Roche Harbor. Some, we learned later, couldn’t find that corner of San Juan Island… not a promising sign. Walking the docks that afternoon, we realized the cruise would include a crazy variety of boats and skippers — some little 16-foot outboard runabouts with gas-station roadmaps for navigation, on up to an ancient 65-foot retired tugboat that would soon tow many of the smaller vessels after they’d either broken down, run out of fuel, hit logs, or otherwise been unable to reach the day’s destination. Aboard the boats were 450 souls — solo adventurers in some of the smaller boats, entire families and some of their friends in larger cruising vessels. Serious skippers, rowdy kids, heavy-drinking guests along for a 1,400-mile party, newbie boaters with zero experience. They were all there…ready or not.

Early interviews suggested a mix of potential stories. Many boaters had never ventured more than a few miles from their home marinas in Olympia, Tacoma, Seattle, and other Puget Sound ports. Some had purchased new boats for the cruise, and showed up with almost no operating hours, spare parts, tools, or idea how they’d get to Ketchikan, other than “following everybody else.” A shocking number had never entered the San Juan Islands by boat, let alone cruised farther north. Most were equipped with paper charts and marine radios; some others had no navigation aids, no compasses, maybe the aforementioned gas-station roadmaps, and only a fuzzy idea of what lay ahead. Boaters who reached Roche Harbor were clearly excited about the adventure, and eager to meet others, exchange stories or seek cruising tips. But overall, Roche Harbor felt like one of those early scenes in a

disaster movie, where viewers are methodically introduced to a variety of innocent characters you know will soon become victims.

Before casting off on the first leg to Campbell River, the 125 boats were divided into six cruising groups, or pods, according to cruising speeds that had been previously estimated, and group leaders were chosen to coordinate daily travels of each pod. Although the leader of one pod had mysteriously vanished, all boats shoved off from Roche Harbor at 7 a.m. on July 20, bound initially for the Canadian Customs checkpoint in Sidney, B.C., and then on toward Campbell River.

It didn’t take long for things to go bad: Only 78 of the 125 boats made it to Campbell River by the end of Day One. We were among the no-shows, having joined a Bellevue family aboard their 44-foot catamaran cruiser, ominously named Still Afloat. We were happy to be guests aboard the big catamaran, since the family’s plan was to cruise in the vicinity of organizer Hardwick, who was aboard a fast twin-engined 33-foot cruiser. After clearing Customs, as we entered Satellite Channel, the skipper of our host boat began a wrestling match with his steering system. At first, the catamaran wouldn’t turn to starboard. Then it wouldn’t turn at all. When we slowed and began steering with only engines and throttles, Hardwick pulled far ahead, running at 17 knots as he entered Stuart Channel. When he was somewhere near what he called False Rock, three miles east of Ladysmith Harbour, we received a frantic radio message from the cruise commander.

“I just hit a log! Didn’t see it at all,” said Hardwick, “and neither did the guy behind me. The port engine is completely dead, and I’m only getting about 900 rpm’s out of the other.”

He was almost powerless and we were completely rudderless. With few choices, Hardwick limped into Ladysmith and we eventually swerved in behind. Before long, a mechanic tore into our boat’s steering system, finding that the autopilot’s desire to immediately return to Seattle had resulted in a steering box full of ground-up metal filings. Hardwick, meanwhile, was in deeper trouble, having been told that nobody in Ladysmith could deal with his bent propshafts, propellers, and rudders. “Try Nanaimo,” he was told by a mechanic, but we soon learned that mechanics in Nanaimo were overwhelmed trying to repair other broken-down boats that were part of the Alaska-bound fleet. In desperation, we located a haulout yard in Silva Bay, Gabriola Island, so Hardwick and his boat limped there, accompanied by the catamaran we were aboard. After all repairs were completed, we finally made it to Campbell River…two days behind some of the leading boats, and falling farther back, since the catamaran’s steering had failed again, along with the boat’s port engine.

Sympathizing with our skipper’s plight, but challenged to cover the flotilla’s cruise from days behind the leaders, Heyza and I chartered a floatplane in Campbell River and flew to the next prescribed stop, Bella Bella, where we caught up with what was left of the armada.

From there, most of the surviving boats made fairly uneventful runs north to Butedale, then Prince Rupert, and on to Ketchikan…not in parade formation, and certainly not via a prescribed route or timetable. But after reaching the final destination, the boaters learned that their fearless leader, Hardwick, was stuck once again with a dead engine and more bent propshafts, having hit another log near Port Hardy — only about halfway to Ketchikan in nautical-mile terms.

After being stuck in Port Hardy waiting for parts and repairs, Hardwick’s boat finally arrived in Ketchikan five days late. On final approach to the Alaska town, Hardwick waved to a lot of folks who were by then heading south back to Prince Rupert and beyond, vowing to slow down and not maintain 100-mile days during their return to Puget Sound.

Finally pulling into Ketchikan, Hardwick was exhausted and disappointed, but relieved. “There were a couple of times when I really didn’t think we’d make it,” Hardwick said after docking. “Especially after hitting the second deadhead. Both propeller shafts, rudders, and props had to be replaced…again.”

When he finally tied up, he was asked to sign the chamber of commerce’s cruise record book. There was only one space remaining in the register, so he was officially the last to arrive.

It was impossible to tell with accuracy how many boats and boaters completed the 1,400-mile round trip from Puget Sound to Ketchikan and back — maybe about 75 went the distance — but the cruise still came close to its description as “the largest and longest pleasure-craft cruise in the history of boating,” or at least “the history of boating in 1968.”

Survivors, gathering in Ketchikan during a four-day layover, enjoyed long showers, and meals hosted by local residents and the Ketchikan business community. They swapped sea stories, many about lessons learned and how, if they ever did anything like this again, they’d take along more spare parts, extra tools, better navigation aids and charts, extra containers of fuel, more food and other supplies, and better communications equipment. While the larger boats had decent marine radio telephones, some of the smaller craft relied on following better-equipped boats, hoping for the best. Fuel shortages were a big issue for the fleet, since refueling docks were often closed — or out of gas or diesel — by the time some of the boats reached overnight stops. Many boats with empty tanks were towed during the cruise, and two of them ran out of fuel 100 yards short of the city dock in Ketchikan.

My most memorable personal experience took place during the long crossing of Dixon Entrance, on the run from Prince Rupert to Ketchikan. Shortly after easing into Dixon Entrance, our ancient host boat encountered the densest fog you can imagine. At that moment, the boat’s large, antique compass began to ooze liquid onto the pilothouse floor. As the compass dial spun aimlessly and then came to rest, we looked at one another and, without speeches or screams, started navigating by dead reckoning… maintaining a steady angle toward the waves, hoping that we’d see land before running headlong into it. Eventually, we eased up to an eerily high and sheer wall of rock, then followed it until we could tell which island we were passing. After that, the fog slowly lifted and we meandered up channels and into Ketchikan, where a new compass was installed.

My most memorable personal experience took place during the long crossing of Dixon Entrance, on the run from Prince Rupert to Ketchikan. Shortly after easing into Dixon Entrance, our ancient host boat encountered the densest fog you can imagine. At that moment, the boat’s large, antique compass began to ooze liquid onto the pilothouse floor. As the compass dial spun aimlessly and then came to rest, we looked at one another and, without speeches or screams, started navigating by dead reckoning… maintaining a steady angle toward the waves, hoping that we’d see land before running headlong into it. Eventually, we eased up to an eerily high and sheer wall of rock, then followed it until we could tell which island we were passing. After that, the fog slowly lifted and we meandered up channels and into Ketchikan, where a new compass was installed.

I was 26 years old when we covered the Alaska cruise, and I’d had a lot of experience with small, open boats, but hadn’t yet cruised north of Campbell River. Growing up in a cruising family, I loved everything about the San Juan and Gulf islands, but was completely unprepared for the staggering beauty of waters farther to the north. Forced to fly from Campbell River directly to Bella Bella, I missed the drama of Seymour Narrows, Johnstone Strait and Cape Caution, but the endless, watery canyons of Graham Reach, Princess Royal Channel, Fraser Reach and Grenville Channel made a huge impression, and I vowed to return. Ten years later, as managing editor of ALASKA magazine, I’d get my chance — spending time exploring Northern B.C. and Alaska waters by pleasure craft, commercial fishboat, floatplane, mailboat, whale-research vessel, and government ferry.

While I’m sure most members of Hardwick’s Alaska cruise took time to savor the magnificent beauty of the Inside Passage during their more-relaxed return leg to Puget Sound, it was striking that their personal stories about the northbound cruise focused on daily challenges more than wildlife or stunning scenery. For most, each day’s prescribed 100-mile leg became a straight-ahead, goose-the-throttle marathon. Often, for the slower boats, it was a 14-hour endurance run with fingers crossed and no time to fully appreciate the environment they passed through enroute to Ketchikan.

But one priceless thing was learned by the Alaska-bound boaters: Townspeople, villagers, and fellow cruisers along the route were unbelievably generous in helping with repairs, food, fuel needs, and other small and large emergencies. Many lifelong friendships were formed, and I’m sure most of the boaters — well, maybe not the guy who put his cruiser up for sale 10 minutes after docking in Ketchikan — used the Alaska adventure as a springboard for years of future cruising experiences. And by the time they completed the 1,400-mile round trip, even rookies had become able boaters who would never again fail to take along spare parts, tools, extra fuel or foodstuffs… not to mention decent charts.

A particularly poignant moment that illustrates the overall camaraderie of the voyage was when a fellow in a small outboard boat limped into Bella Bella with a blown head gasket in his 75-hp outboard. Late at night, knocking on doors in the old Bella Bella village, he was guided to an elderly tribal member — a boater who was known for his collection of keen junk. “You wouldn’t by chance have a head gasket for my 75-hp outboard, would you?” the visitor asked, fearing the answer. “Well, let’s see here,” the man replied, beginning to rummage through a hodgepodge stack of used parts. In mere minutes, the amazed visitor heard, “Sure, here’s one,” as the elderly gent handed over a floppy, used gasket for the exact motor. After refusing offers of payment, the two heartily shook hands and the stranger disappeared into the night, now ready for his final push toward Ketchikan.

Boaters helping boaters. That’s how it was in 1968 when a lot of them needed assistance, and how we hope it remains today.

Background title photo by Nick Reid.

Marty Loken

Marty Loken is the Associate Editor of Small Craft Advisor magazine, based in Port Townsend, Washington.