From the March 2004 issue of 48° North by Kaci Cronkhite

It was a sticky hot monsoon day in January. An urgent call had come in for me via the marina manager. What I thought he said, but I found hard to believe, was that I needed to go to the Thailand Customs and Immigration Office immediately. Confused, but not one to argue with Customs officials, I shed my diesel stained “scrubs,” a gift from one of our learning crew who was a doctor in Bremerton, cleaned up what I could and tried to squeeze into my “city ‘official’ clothes.”

After a relatively mild but always-exciting taxi ride, I unpeeled myself from the seat and walked into the refrigerated air of the Customs Office. Eight finely dressed officials smiled at me as I weaved through the ropes for “lines” that didn’t exist. When I got to the end of the maze, an official in the back corner motioned me over. Fourteen dark eyes watched.

After a brief hello in Thai, I lay my file of paperwork on the desk. He looked at it, then said, “You must pay $1,000 dollars.” Trying unsuccessfully to hide my gasp of disbelief, I opened the file to show him that all our paperwork had been completed and approved. More than a month earlier, we’d crossed the border into Thailand, from Malaysia, like fifty other cruising boats and we’d heard on the morning radio net about a few corrupt officials who were trying to extract extra money from cruising boats who’s owners left the boats to travel inland. Based on their experiences and advice, we’d completed extra paperwork to ensure that Tethys could stay in the country until Nancy returned from the US. The boat paperwork was clear, but my passport needed to be renewed.

This was not a new problem, since each year during our circumnavigation, she would fly back to Seattle to do talks and meet people who were interested in learning offshore sailing with us. While she was away, usually for one month, I’d undertake major refit, repair and maintenance projects. It was routine for us to have notarized papers and to do other things to appease officials and show that I was also a Captain, and approved by the owner of the boat to handle all matters dealing with her.

“Not so, Thailand,” said the official. “You must pay this amount or leave the country.” After a few more futile attempts at communicating, I asked him to go ahead and process papers for us to check out of Thailand. He looked around at the other desks. He looked back at me and said, “Where crew?” I pointed to myself and said, “Me.”

Later, on the way back to the boat, a bit of panic set in. What had I done? How could I really take the boat out of the country in 24 hours?

At the marina, I surprised the manager and told him I was leaving tomorrow, and then paid our bill. Next, I proceeded to Shemali Blue, home to a family I’d only just met the day before when their precocious and adorable daughter Eleanor had come to introduce herself to me minutes after they’d docked. Apparently, her grandmother was aboard from England, and she wanted everyone in the marina to meet her. Queen Elizabeth, she was not, but instead a charming elderly countrywoman who I was pleased to join for sundowners in their cockpit that night.

Quickly, we moved past our brief acquaintance as they empathized with my plight. There wasn’t time to call Nancy and I knew there was little she could do but worry if I phoned. Both Carda and Peter were quick to conspire with me on a route and radio schedule. I gave them her name, and my mothers in case something happened. They suggested some anchorages we’d not been in, which made me nervous. But I made careful notes of rocks, shallows and their other notes.

The tides through the marina were atrocious, so one of my next tasks was to start monitoring direction and strength. I needed to leave within 24 hours, and I desperately wanted a slack tide and daylight. The day before, a motor yacht had a nasty encounter with an aluminum skiff when their full keel got crosswise to the current and they were powerless to overcome it. Tethys 19-tons and very full keel only had a 22.5 horsepower Saab to move her without wind. I knew I had to move when the tide was slack.

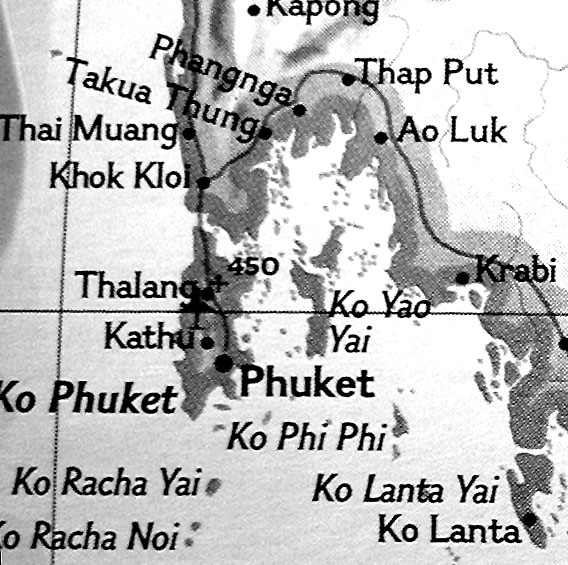

As the night set in, the tide slackened. It looked like dawn was going to work. The inspiring monoliths of Phang Na lay to the north, just around the corner from our marina at the north end of Phuket. Once I was out of the marina, I could head that direction, and depending on wind, had several choices of anchorages, including the unknowns my friends had mentioned. The rest was only a vision. At times, it was almost a nightmare. At other times, I was high on the possibility of setting off alone. I planned for everything I could imagine might happen.

Setting off

The sky was just starting to lighten when my watch alarm beeped. The humid air was cool and had that fresh blossom smell so common in the tropics. I looked outside at the string I’d hung in the water. It was waving gently, telling me the tide was still flooding, but easing now. The teapot whistled and as I went to turn off the propane stove, I heard my friend Carda whisper toward the porthole. “Are you up?”

I whispered back for her to come aboard for coffee. I’d prepared the decks and cabin, put in three routes of waypoints and taken off the sail covers. While she started to talk at normal volume in the cabin, I started the engine. Exhaust water, fine. Oil pressure, steady. Nav lights and radar and knot meter, all on and functioning.

We talked quickly as we went up top to recheck the current. It was barely flowing. It was time. I eased the boat into reverse while Carda cast off my last two lines. “Good luck,” she said. “Call us at 1700 and again at 18 and 1900 if we don’t make contact.”

I backed the boat right up into the corner as I’d watched Nancy do a million times. Tethys didn’t like to back that direction and I knew I’d need all that room to swing her around to head out. It worked. As I gave her forward speed she turned and it brought me near Carda on the dock. She blew me a kiss in that wonderfully easy European way, and I was off just before the sunrise.

As I turned to starboard and cleared the marina docks, I rechecked the charts and my heading. The sun came up and its heat came rushing into the morning mist. I had good depths, so I went forward and hoisted the main. There was barely any wind, but I wanted to have the sail up before it started. Next, I flipped the fenders over the lines, went back to the cockpit to correct my course, then again moved around the boat removing dock lines. Back and forth, I went taking off lines, carrying them to the cockpit, correcting course, and then repeating the whole exercise. This was a lot of work!

I cleared the channel and the tide began to flow again, with me. I looked to port at the monoliths, the mint green and grey waters reflecting in surreal patterns. I had to make a decision. North or south? Through the shallow islets of James Bond fame, or safe to deeper water with a further anchorage in reach by nightfall? I shoved the tiller to starboard. North it was! I swung below and grabbed the detailed charts.

Suddenly, there was a “knock, knock, knock” on the hull. I leaped up the companionway and found myself staring into the big smile of a Thai woman, hanging onto Tethys cap rail and holding up a bag of huge tiger prawns. Her presumed husband was quietly holding the tiller of their long tail boat in his armpit, relaxing while we dragged them along. Knowing she would not take no for an answer and seeing the shallows quickly approaching, I grabbed some baht and paid her for the shrimp. She let go and they sat smiling at me as we pulled away from them. Did they know I was alone?

I couldn’t spare a minute to worry, as I was now watching the depth sounder. Shifting sand bars and bad charting are common in these waters. The silty water made it impossible to see, so I trusted the charts and held onto the tiller. Ahead lay the most dramatic sheer walled monolith of all, the site of James Bond’s filming of Man with the Golden Gun. Although it wasn’t labeled on the chart, there were dozens of boats anchored or long tails motoring tourists around it. I dropped below for the video camera.

Back in the cockpit, I checked my plot on the map, noticed the sand bar allegedly nearby and pushed the button to film. I don’t know how long I filmed, but it seemed like only seconds later that Tethys bumped hard! I shoved the tiller to port; bringing her bow sharply back towards what I hoped was the deeper water. We sat still. We rocked. I started to sweat. Then, went forward and hoisted the staysail. A bit of wind had started and now that I wasn’t running with it, I could feel it off my beam. Sure enough, it filled and as I rocked the rudder a few times, I felt Tethys start to move. “Eureka!” My heart pumped harder as I prayed I’d continue to move. In seconds, the depth went from 10’ to 5.3’ (Tethys draws 6’) then back to 8’ and we were sailing! Nervously, I held the tiller. The video camera lay abandoned for the rest of the trip.

Having made the choice to sail into unknown waters (Nancy and I had cruised most of the other island areas), I now had to figure out which anchorage I should aim for. The weather fax indicated steady weather, so I opted for a place the Brits had recommended, Ko Roi.

Blissfully empty and a perfect depth (30’) for our manual windlass and all chain rode combination, Ko Roi welcomed us. I circled the tiny bay, stopped the boat, dropped the hook just enough to touch bottom, then set the tension so it would roll out slowly as I gently reversed. When I saw the 90’ marker roll off the gypsy, I put the boat in neutral and headed forward again. As 120’ approached, I tightened the break, flipped the pawl into position and looked around me. Perfect. I started to sweat. That’s what I’d thought before! I backed down on the chain, felt a good tug as the CQR dug in. I cut the engine, dropped below to make a log entry. “Time, 1311. Bar, 1008. Many long tails. One Sunsail Yacht. All well.”

My first day of single-handing had ended. I set my watch for the radio schedule and fell asleep on the console. I must have been relieved because I slept through the alarm. When I woke at 1930 and turned on the Ham radio, I could hear Peter calling. “Here’s KI7DP,” I said. No response. We’d put in a new radio recently and this was my first attempt to use it. Try as I might, it would not transmit. I dug through the lockers, found the old one and reconnected it. It took me too long, though and I sat depressed and alone. At around midnight, I pulled out the charts and began to plot several options for routes and anchorages for the next day. My spirits lifted.

At dawn the next morning, I began the arduous task of taking up the anchor. I’d go forward, manually take in 30 feet of chain, drop through the forward hatch, knock down the chain pile, continue through the boat, up the companionway into the cockpit, nudge the boat forward, walk up to the bow, take up more chain, then repeat the whole pattern again. It took about six trips. There wasn’t a lot of room in the anchorage and I was near several rocky promontories, so I opted to squeeze through a narrow and surprisingly gusty pass. Frantically I checked and rechecked my chart and depths. All ok.

In the clear, I let the boat head up into the wind and I raised the reefed main. Tethys eased ahead. The wind was still forward of the beam, so I hoisted the staysail, too. She heeled and I trimmed the sails. Our speed and the changing land breeze were slightly increasing, so I rolled out the genoa. We were sailing!

The boat was perfectly balanced and all was clear, so I hopped below for the 0630 cruisers radio net. I wanted to let someone know I was ok. The log reads, “Yea! Radio with Ragtimer, Shemali Blue and Gigolo. Beautiful sailing.”

By 1100 the wind had filled in. “Rock n Roll,” I wrote in the log. “25 knots, 4’ breaking seas. Falling off to Phi Pi Don.” I eased the sails and headed off the wind. Shemali had decided to head out from the marina and meet me, so I watched for them to clear the big island between us. When I finally caught site of their robin egg blue hull, I called them on the radio. We made plans to check out Phi Pi Don together, but Peter asked that I take a look at another new anchorage, Lanta Yai. Since I’d been up much of the night and was determined to be anchored before sunset, I told him my concerns. We agreed to make our decision later in the day, to check our progress towards the anchorage, the wind speed and direction and my tiredness. We rounded the point at Phi Pi Don together with a great breeze. Now, we could see Lanta Yai in the distance, a two-hour sail. As I started below to answer the radio, I heard a strange sound and the genoa started to flog. I looked up to see a tear opening up the full length of the leech! Ignoring Peter’s call, I quickly eased the sheet and started rolling it in. Now, without a jib, Tethys slowed considerably. I dropped below to consult with my friends and consider the options. They were racing ahead of me now and knew they’d make the anchorage by sunset. I wasn’t so sure I could make it. The Phi Pi Don anchorage was very crowded and deep. I didn’t relish the idea of going in there alone. The anchorage ahead was big, muddy (good) bottomed, and I’d have Shemali Blue there to help me with the sail. I turned on the engine, rechecked my distances and speed, and decided to head for Lanta.

Just before sunset, I pulled into the anchorage, dropped the hook like I’d done it a million times, and then proceeded to get the genoa off. The wind had died. I rolled out the sail and loosely wrapped one sheet around the winch. Easing the halyard, I gave the sail a tug and it started down the track. I could see Peter and Carda getting into their dinghy nearby, but needed to keep working. Soon, they climbed aboard and helped me drag it down through the hatch and across the main salon where I could sew it. We hugged, slapped hands, and they invited me over for dinner. It was 1740. What a day.

After dinner and some brews, they delivered me back to Tethys where I began a 6-hour “speedy stitch” repair of the leech. Aching with tiredness, I chuckled at the name of this nifty tool and at some point, fell asleep.

Next morning, the Shemali’s came over to help me ease the repaired sail back up its track. There was a breeze now, of course, so the heavy flailing sail was cumbersome and any tension on the sheets would set Tethys sailing on anchor. Not fun. In less than 15 minutes, we had the sail up and rolled away. They wanted to head for a dive spot, and it was time for me to make tracks for Malaysia. We waved goodbye and promised another try at the radio sched.

Tethys and I sailed on through the afternoon. The sheer wedge of Ko Phetra (an amazing islet where sticks of bamboo are layed end to end in unsteady looking patterns used to climb the walls and gather bird’s nests for soup) grew closer in the distance. Several groups of fishing boats were anchored along the way, hanging on one hook together, their crews resting from the night’s work.

Suddenly, a puff of black smoke spurted from one of the boats ahead of me. Then, a second boat started its engine. This seemed strange to me. I turned on the radar. The anchored boats were 3.25 miles ahead and I was doing 8 knots. Closing quickly, I watched as they took up their anchor. I held my course, feeling tension in my stomach. Something was odd. With only a quarter mile between us, I could see the boats were loaded with men. I watched as one boat threw a rope to other connecting their sterns. A net began to go over the side between them. I knew that some of the bigger boats dragged a net between them, sweeping the bottom for prawns. But fishing at two in the afternoon was strange.

I realized Tethys was heading between them. I knew that “fishing” they had the right of way. But I also knew they would have seen me sailing toward them for hours. My gut said something was wrong. Within minutes, I made the decision to hold my course and radically fall to starboard if they continued to drop their nets. The wind was blowing a steady 25 knots and Tethys was racing along. Two boat lengths from their boats, I pulled the tiller hard to port, dropped the main traveler and turned at nearly a right angle to them. They hooted and laughed and waved at me. Once past, I waved back and watched, confused as they pulled their net back in.

After a nervous, but uneventful night at anchor, I sailed the last few miles into Malaysia’s Rebak Marina. I eased through the channel and into the slip, all my lines ready and my fenders down.

A friend we’d met earlier stuck his head out through a hatch. “Good morning,” he said. “Where’s Nancy?”

“In Seattle,” I smiled, as I hopped to the dock with my lines.

“Where’d you come in from?”

“Thailand,” I replied.

“Did you hear about the Pirates in the fishing boats, or see any?”

I breathed a sigh of relief and told him I’d tell him the story later. My first and only international single-handed “delivery” was complete. I faxed Nancy and told her the good news, then went fast asleep.

48°N

Joe Cline

Joe Cline has been the Managing Editor of 48° North since 2014. From his career to his volunteer leadership in the marine industry, from racing sailboats large and small to his discovery of Pacific Northwest cruising —Joe is as sail-smitten as they come. Joe and his wife, Kaylin, have welcomed a couple of beautiful kiddos in the last few years, and he is enjoying fatherhood while still finding time to make a little music and even occasionally go sailing.