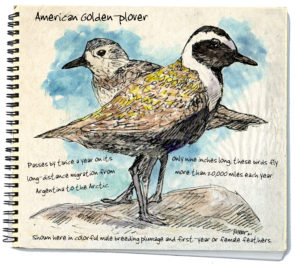

Last spring, I saw hundreds of American golden-plovers on the western wilderness beaches of Olympic National Park. They were spending their days resting and eating sand flies, then at dusk they would rise in a rush of wings and head north, using the safety of darkness to fly. Migration is a long journey for these nine-inch birds. They winter in Argentina and Uruguay, then fly all the way to the Canadian Arctic to nest — and then return. Repeat yearly! They can do that because of the swept-backed skinny shape of their wings, and comparisons to tall windward sail designs is obvious. It’s still a dangerous and grueling journey twice a year — they live lives on the wing. Once on the nesting grounds, males build crude nests lined with lichens and four eggs appear. Males incubate by day, females at night. Chicks can feed themselves within a few hours of hatching, and my guess would be that it takes four chicks per pair each year to replace the birds lost during those long migrations.

I have pleasant memories of those birds last spring, but then kayaking along the outer breakwater at Port Townsend recently, I saw a large flock of golden-plovers sitting on the rocks. Some still had their summer feathers, along with a bunch of youngsters in drab browns, and it was like seeing old friends again. I quietly floated right up to them, had a good look and then they flew in a cloud and came around to land just a few yards away. I wondered if any of these were the very same birds I saw a few months earlier and realized how connected we all are to wildlife — if we only are aware of it. Boats were coming and going right over on the breakwater’s other side, yet here was a little community of birds from Argentina and the Arctic, just gabbing away at each other. It’s not only what you see when you look, but also what you understand.

Larry Eifert

Larry Eifert paints and writes about the Pacific Northwest from Port Townsend. His large-scale murals can be seen in many national parks across America, and at larryeifert.com.