“Why would you want to write about a worm,” my editor once asked? As with all of nature, even seemingly mundane creatures can be very interesting. Every temperate ocean has teredo worms, including the Salish Sea.

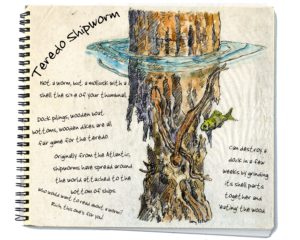

They’re not a shipworm, not even a worm, actually, but an odd bivalve related to clams that has two shells wrapped around only its head. The rest of the body is unprotected and can sometimes become two feet long. The two thumb-sized shells grind wood to dig a protective tunnel into any underwater wood, lining the sides with calcium from the discarded wood fiber like a calcareous tube worm does. A bacterium that lives with the creature helps it ‘eat wood’ as it moves through a floating dock, piling, or a piece of sunken driftwood. At the mouth of the creature’s burrow, two tubes (inflow and outflow, as all clams) wave out of the hole to catch food and release excretion. As the creatures grow, they extend the tubes farther into the wood. In as little as 4 months, teredos can completely riddle a Douglas-fir piling. Wooden boat bottoms — no problem, these guys used to make Swiss cheese out of the bottoms of great square riggers and frigates. The British Navy once clad the bottoms of the entire fleet with copper sheets to keep them out. It wasn’t until modern toxic bottom paint came along that the threat somewhat subsided; but these bivalves are still out there.

Not to be socially outdone, a shipworm is born when larvae are released into the water, leaving the syphon of the female. All are born as males. They quickly become sexually mature and release sperm into the sea, but then dads change into moms at about 2 months. As they mature into adults, all teredos search for a suitable log or dock in which to set up a new home. After digging in, the females in their wood tunnels are fertilized when floating sperm gets sucked into the bivalve’s syphon. Soon, more than a million larvae are conceived and brooded in a single teredo’s gill chamber. Who wouldn’t want to write about all this?

Larry Eifert

Larry Eifert paints and writes about the Pacific Northwest from Port Townsend. His large-scale murals can be seen in many national parks across America, and at larryeifert.com.