Last week I received the all-too-common call for help: “My engine won’t start and I don’t know why?”

When I arrived, I discovered that this engine was an old 1970s Yanmar YSB 8 single-cylinder engine that is raw water cooled, meaning it is cooled with raw water throughout the engine block, without a heat exchanger mounted or coolant employed.

I knew before I dug into the actual issue that I’d be opening a can of worms. The vast majority of the time, I find myself condemning these engines as they are not worth the money to fix or are in such dire shape they will never run properly again, even if we fix the problem I was called to diagnose.

What about these engines is so bad, though? Why are folks advised to avoid them like the plague? I’m here to share the gritty parts about raw water engine ownership that will hopefully help you decide if you want to avoid them or not.

During the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, several manufacturers came out with the raw water cooled engine as a cheaper alternative to their most popular lines of engines they had on the market. Those of you who have repowered or shopped around for marine engines already know just how expensive these little engines can be, so a budget-friendlier option was a welcome addition to the market. For context, most sailboat engines today range from $11,500 to $40,000 or more depending on size, and larger powerboat engines can have price tags that range from $60,000 to over $100,000.

It is most common to encounter raw water diesels on sailboats, since larger engines were generally not offered in a raw water configuration unless it was an antique engine or a commercial plant with water purification systems for the water jacket cooling systems onboard.

Raw water cooled engines were generally about half the price of the equivalent “fresh water cooled” (coolant cooled) engines. For example, Yanmar’s popular GM series included both fresh and raw water engines, with the difference clearly identified by an “F” at the end of the engine model. A Yanmar 2GM20F was a fresh water cooled engine with a heat exchanger mounted and coolant circulating through the engine block, while a Yanmar 2GM20 was the raw water equivalent of that engine. They were the same or similar engine block, just using different cooling methods and with dramatically different costs.

Raw water engines were built as the cheaper, more “disposable” option for a repower. Their operating life was never meant to be as long as their fresh water counterparts; however, they have proven themselves to be quite resilient over the years, lasting far longer than anticipated. Most raw water engines (unless you are in a body of freshwater) are circulating saltwater throughout their engine blocks. Add saltwater to a cast iron engine block, and the engine’s life is significantly changed. Certain manufacturers, such as Yanmar, built their engine blocks with porcelain embodied in the cast iron, along with adding engine zinc anodes to their engine blocks, making them extremely corrosion resistant for many years, while other “marinizing companies” such as Universal simply used Kubota engine blocks originally built for tractor applications that couldn’t compete with Volvo or Yanmar for corrosion resistance.

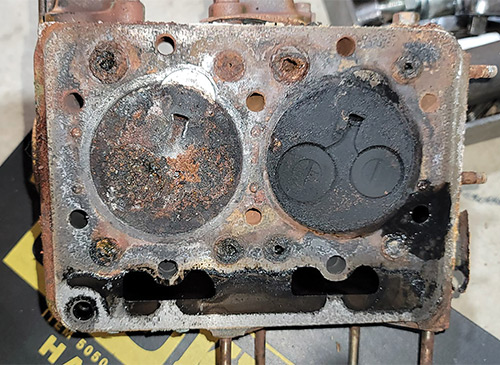

Despite how well these engines may or may not have been built, no engine will survive corrosive liquids forever. Both saltwater and freshwater (lake or river) can wreak havoc on various metallic surfaces over time. While there are still raw water cooled engines out there in service, I am finding that many of them, including the ones in a less corrosive environment such as the Columbia River, are reaching the end of their lives. I am seeing various forms of metal fatigue (cracking/warping) and corrosive damage (rust, barnacle-like build-up) in addition to general wear and tear.

Most raw water cooled engines I work on today are in pretty tough shape. While I hate to be the bearer of bad news when I recommend a repower, I am seriously impressed that many of these engines are 50-plus years old and some are still running or have just recently given up. That’s not bad for a “half-price” engine designed to last 10 years or less!

These engines typically make it fairly obvious when they are ready to permanently retire. You’ll notice the engine becoming more and more difficult to start, or it won’t cool efficiently anymore and will begin to overheat when it didn’t before. This is the result of buildup within cooling passages that is so solid no amount of “salt-away” or “Barnacle Buster” will help you. Metal fatigue also takes hold after a while and these engines tend to crack wide open, resulting in the engine never starting again. I have seen pistons broken in half, and cylinder heads and engine blocks with huge cracks that were not the result of overheating like one would expect, but instead just came out of nowhere.

While I can still buy rebuild kits for certain engines such as the Universal 5411, it is not worth it if the engine has been raw water cooled. I have a few training engines I use for classes that are raw water cooled. Though I also have the complete rebuild kits for them, if I were to rebuild them, they would simply overheat as their raw water passages are so badly corroded, they would never be able to cool themselves efficiently, especially with a fresh rebuild that restores the power the engine was designed to have.

A common issue with these engines is that they tend to run much colder than they should. Their equivalent coolant cooled counterparts are designed to run at approximately 180 degrees Fahrenheit, and the coolant temperature remains fairly consistent at that temperature as long as all systems are functioning properly. A raw water engine, whether it is pulling river water or ocean water, will have ranging temps circulating through it at all times, whether you are in 60 degree California waters or 45 degree waters of Puget Sound, these engines tend to run too cold at about 140-170 degrees. This lower running temperature causes a lot of soot/carbon buildup from improper combustion. Soot and carbon are extremely abrasive and harmful to any engine and will damage cylinder walls, valves, pistons, rings, injectors, and exhaust elbows. On most raw water cooled engines that I take apart, there is more abrasive wear and tear on average than that of the fresh water cooled equivalent.

So, are these engines something to avoid? If you currently have a raw water cooled engine, treating the cooling system with fresh water flushes and barnacle buster can prolong the life enough for you to make plans for the future, but it will be important for you to keep in mind that this engine will eventually have an expiration date and you want to be prepared for that. Keep taking care of it the way you normally would, though, as you may still get several years of faithful service.

If you are shopping for boats and run across one with a raw water cooled engine installed, it is wise to have a good mechanical survey to determine what the engine’s future may entail. A good mechanic will be able to tell you if the engine is approaching the end of its life based on how it starts, whether it smokes, whether it efficiently cools, and more. If you are ok with a potential future repower and it’s your dream boat, by all means, go for it! As someone who loves to tinker, engine issues were the least of my concerns when buying a boat. On the other hand, if a repower in the near future is not something you desire, then I would advise purchasing with caution. When asked for my professional opinion, I usually encourage folks dealing with these engines to avoid dumping excess amounts of money into them, but to maintain them the best you can on a limited basis while also saving for a newer engine that is worth putting your money into.

Raw water cooled engines were an amazing option of their time. I am not sure whether you can still buy a raw water cooled engine—I did note that Yanmar still had their 1GM10 single cylinder on their website, however, whether you can still order one is unknown. At half the price, they were an affordable repower option that far exceeded their own expectations. You should approach these engines with caution as many of them are at the end of their service life. I hope that manufacturers will consider continuing to have these alternative engines as an option so consumers have more choices when repowering in their small sailboats.

Meredith Anderson is the owner of Meredith’s Marine Services, where she operates a mobile mechanic service and teaches hands-on marine diesel classes to groups and in private classes aboard clients’ own vessels.