This beacon might be the most remarkable in Washington. Part of a chain of lighthouses spanning the Washington coast, it is the state’s tallest, rising 107 feet above a thicket of seagrass and dense vegetation. Lighthouse architect Carl W. Leick reportedly considered it to be his masterpiece — and many observers agree.

“If one had to choose the most impressive watchtower in the Pacific Northwest from an architectural standpoint,” wrote maritime historian James Gibbs, “chances are it would be Grays Harbor Lighthouse.”

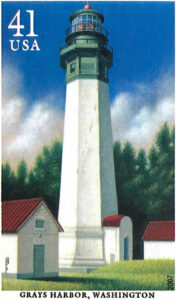

Its sleek white tower and Italianate flourishes were featured on a postage stamp in 2007. While this beacon now stands a half-mile upland from the high tide line, it continues to guide mariners to the southern entrance of Grays Harbor, lighting the way from Point Chehalis.

A Tall Light in an Unusual Setting

The setting is not typical for coastal lights in the Pacific Northwest. While many beacons sit high above the sea on dramatic bluffs (see the column on North Head in the November 2021 issue of 48° North), the Grays Harbor Lighthouse rests on a sandstone foundation in the middle of low-lying coastal dunes, making its great height necessary. The tower was placed nearer to the water in 1898, but over the years land accretion has extended the beach, increasing the distance to the pounding waves. Today, the top remains visible from the sea, soaring above the trees that now surround the lighthouse.

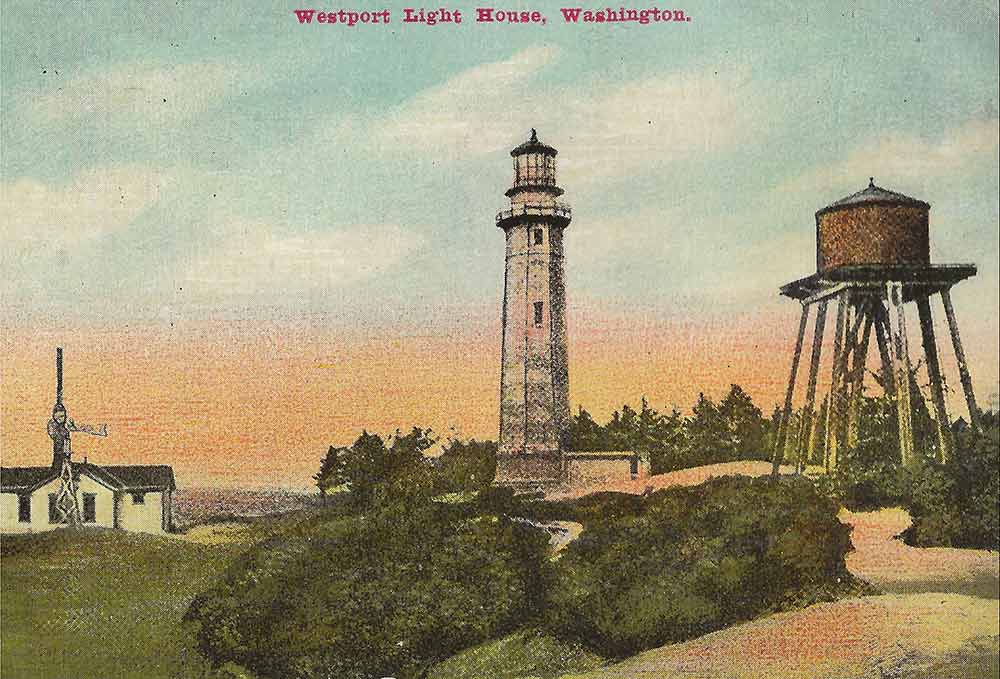

Located on the traditional lands of the Chehalis people, the beacon was also called the Westport Lighthouse after the community that grew around the logging and fishing industries more than a century ago. The United States Lighthouse Board initially considered a shorter, less powerful harbor beacon for this site. During the late 19th century, however, Grays Harbor became a timber port of global significance, dependent on maritime shipping. A major coastal light was a more suitable aid to the vessels arriving from distant locations to enter the treacherous waters of the Washington coast. Accordingly, the Grays Harbor light station included a lens that could be seen for 20 miles at sea, along with a fog signal.

Light Station Features

Construction proceeded quickly in the late 1890s. “The big tower,” observed one reporter during construction, “is climbing skyward as fast as an army of expert men can lift it.” This speed did not affect the quality, as “Leick allows nothing but first-class material” (Seattle Daily Times, October 3, 1897). The station, which was dedicated in a ceremony in 1898, was the pride of Westport. It included a tower, fog signal building, windmill, water tank, two oil storage houses, and two dwellings — one for the head keeper and one for the assistant keepers.

Construction proceeded quickly in the late 1890s. “The big tower,” observed one reporter during construction, “is climbing skyward as fast as an army of expert men can lift it.” This speed did not affect the quality, as “Leick allows nothing but first-class material” (Seattle Daily Times, October 3, 1897). The station, which was dedicated in a ceremony in 1898, was the pride of Westport. It included a tower, fog signal building, windmill, water tank, two oil storage houses, and two dwellings — one for the head keeper and one for the assistant keepers.

The octagonal tower was made of brick covered by cement, eventually painted white. Cast iron brackets, window hoods, and a front gable over the workroom added to the visual appeal of this otherwise utilitarian structure. A long series of metal steps spiraled up to the lantern room, which housed a third-order “clamshell” Fresnel lens, manufactured by Henry-Lepaute of Paris in 1895. This device floated in a drum of 20 gallons of mercury, allowing for a smooth, frictionless rotation by a weight that hung inside the tower. The light produced alternating red and white flashes.

The fog signal building became operational in 1899. A windmill pumped well water to a coal-fired boiler, powering two trumpets that projected toward the water. The fog signal system burned up to 200 pounds of coal per hour when the trumpets were sounding.

The Keepers

Christian Zauner, the light station’s first head keeper, arrived in 1898 with his wife and two daughters. Born in Austria, Zauner had transferred from the beacon at Destruction Island — and he remained at the Grays Harbor lighthouse until his retirement in 1925. Nighttime responsibilities included adjusting the oil lamp that provided the light source for the lens, which was polished during the day. According to Zauner’s log, maintaining the fog signal system was an especially arduous task.

“It requires one’s whole attention to keep steam pressure up to the notch,” he wrote. During the early 20th century, the fog signal burned and was replaced with an oil-fired device. Several accounts of his tenure at this lighthouse note that Zauner detected major earthquakes around the world by observing the weight hanging from the tower stairs, which would sometimes swing violently. No keeper at the Grays Harbor Lighthouse stayed longer than Zauner, who continued to live in Grays Harbor after retiring, settling into a house just a few blocks from the station.

Arvel Settles, whose boisterous family eventually moved to the Lime Kiln station (see column in July 2022 issue of 48° North), arrived in 1930. He, his wife, and five children resided in the main house, visiting Aberdeen for supplies to supplement government provisions. “There was always a full ham hanging in the pantry,” recalled one of his sons. Settles transferred to Lime Kiln in 1935, and Roy “Sharkey” Jacobsen became head keeper. When the U.S. Coast Guard and the Lighthouse Service merged in 1939, “Sharkey” signed on as a coast guardsman and remained at the station until his retirement in 1945.

The Lighthouse Today

The Lighthouse Today

The Coast Guard automated the Grays Harbor beacon in the 1960s. The light, once fueled by kerosene, was replaced with a smaller electric unit in the 1990s. The original Fresnel lens remains in the tower alongside the new light, which visitors can view during tours operated by the Westport South Beach Historical Society.

Today, mariners near Westport look for the light’s signature flash of white followed by 15 seconds of darkness, then red followed by 15 seconds. They join the sailors who for more than a century have relied on this stately beacon — Washington’s tallest and perhaps most beautiful — to point the way home.

For more information, see: https://www.wsbhs.org/lighthouse

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor living in Seattle.