Is it cheating… or just smart?

The wind was up, the slip was tight, and the peanut gallery of marina neighbors had assumed their usual spots. Perched in cockpits, coffee mugs in hand, performing their silent critiques. As I backed into the narrow berth, a friendly nod came from a guy two slips down, the kind that says, “Nice job, skipper.” For a moment, I basked in the pride of a maneuver well executed. Then the unmistakable whir of the bow thruster echoed off the dock pilings. The nod became a knowing smirk. Pride gave way to sheepishness. Well, so much for impressing the locals.

Bow thrusters have become a flashpoint in the ongoing debate over seamanship, technology, and what it means to “really” know your boat. Some sailors consider them a vital docking tool, the mark of a practical skipper who values control and safety. Others dismiss them as crutches; something that erodes boat-handling skills and cushions you from learning how your vessel truly moves. So, are they necessary? Or just nice?

To answer that, we have to begin with what they are. A bow thruster is a small propeller mounted near the front of a boat, typically in a tunnel running athwartships (sideways) through the hull, on an external pod, or in a retractable unit. It allows the bow to push port or starboard independently of the main engine or rudder, making tight maneuvers much easier. They’re especially useful at slow speeds where most sailboats become sluggish or unpredictable, particularly in reverse. On some boats, especially those longer than 40 feet, have dual rudders, or with substantial freeboard, bow thrusters are included as standard equipment. But even on smaller vessels, retrofitting one has become a popular upgrade among coastal cruisers, liveaboards, and aging skippers who want to ease the strain of docking in dicey conditions.

There is a reason why cruisers of all kinds love them. Few chores spike your heart rate faster than docking in a stiff crosswind with current running and only six inches between your toerail and someone’s sparkling topsides. A bow thruster offers an escape hatch from that particular flavor of panic. It lets you correct a blown approach or counteract windage with the push of a button. When your crewmate is stepping off with a dock line, or when you’re alone at the helm trying to lasso a piling, having lateral control over the bow can prevent a whole host of mishaps—not to mention bruised egos.

For shorthanded crews or solo sailors, it can mean the difference between taking the boat out or staying within the safety of a slip. Owners can install a remote-control system in tandem with their controls at the helm that activate the thruster’s solenoid electronically. These remotes allow the operator to control the bow thruster from virtually anywhere on the boat, adding a valuable layer of versatility and convenience, especially when docking or maneuvering solo.

In crowded marinas or popular anchorages where space is tight and slips are narrow, bow thrusters can reduce the stress of threading the needle. They’re especially helpful on boats that catch the wind or water and complicate precise movements—those with high topsides, full keels, center cockpits, or tall rigs. On most production boats, they can only counteract wind forces up to about 20 to 25 knots, and many seasoned sailors acknowledge that docking a long, heavy vessel in close quarters requires a different skill set than sailing. In these situations, a bow thruster can make a big boat feel smaller, nimbler, and far more forgiving.

A bow thruster can also be an invaluable asset during a soft grounding. Sea Otter Cove is one of the northernmost anchorages on the west side of Vancouver Island—beautiful and well-protected. However, its entrance channel is shallow, narrow, unmarked, and constantly shifting. Last summer during an early morning departure, our keel gently found the mud as the boat came to a slow stop in the shallows. With careful use of reverse coupled with the side-to-side maneuvering power of the bow thruster, we were able to wiggle free and get back underway with no drama.

Still, bow thrusters come with trade-offs; starting with cost. Factory-installed units on new boats can easily add several thousand dollars to the price tag. Retrofitting a thruster into an existing hull is an even bigger undertaking. It requires hauling the boat, cutting a custom hole in the bow, glassing in a tunnel, running heavy-gauge wiring to a dedicated battery bank, and installing the control systems. A client of ours recently added a tunnel-style bow thruster to a 45-foot sailboat, with the total cost topping $14,000. The price can climb even higher if your boat requires a retractable thruster, or if installation is complicated by limited access or components, like a freshwater tank beneath a V-berth that must be relocated.

Another downside of bow thrusters is their significant energy demand. Electric bow thrusters draw substantial power and their consumption increases with thrust capacity. Thrusters are typically rated by the amount of lateral force they produce (usually in kilograms) and by their corresponding power draw. Simply put, more thrust requires more energy. To see just how demanding these systems can be, we partnered with Skagit Valley College’s Marine Maintenance Technology Center in Anacortes. Using state-of-the-art multimeters, we tested a 100 kg-rated bow thruster in operation. Our amp clamp recorded an inrush current spike of 1,231 amps at 12V DC, before quickly settling to the manufacturer’s nominal rating of 740 amps.

This highlights the need for properly sized and well-maintained battery banks, wiring, and connections. You’ll need to account for that in your electrical system planning. Some owners go so far as to add a separate battery bank forward to minimize voltage drops or sluggish thruster performance. On top of that, maintenance can be a recurring headache—especially in saltwater environments. Corrosion, maintaining zincs, marine growth, and motor failures aren’t uncommon, and most repairs require a haul out.

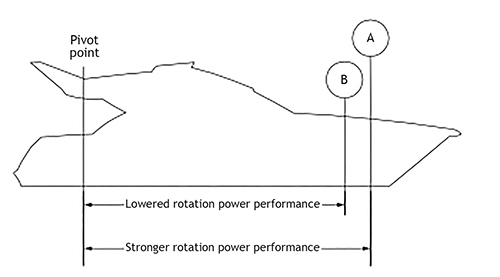

Modern hull designs favor flatter bottoms and shallower drafts near the bow. This makes it difficult to install a tunnel thruster far enough forward of the boat’s main pivot point for good leverage or deep enough to avoid cavitation. Retractable bow thrusters offer a solution to this challenge. A retractable bow thruster is a motorized propeller unit that folds up into the hull when not in use and is lowered into position when needed. Retractable bow thrusters allow for their installation to be farther forward, providing greater leverage, improved thrust and reduced drag, since the thruster remains enclosed within the hull when not in use. This is an especially valuable feature for racing yachts. However, retractable thrusters come with a larger price tag and require proper maintenance, as they can become jammed by marine fouling when neglected.

Perhaps the most overlooked drawback, though, is a subtle one: the potential erosion of boat-handling skills. It’s easy to let the thruster become a first resort instead of a backup tool. I’ve watched skippers hit the joystick before even checking wind direction or thinking through a spring line maneuver. When that becomes the habit, situational awareness and seamanship start to suffer. And if the thruster fails, which is a possibility each time it is used, you’re left reacting instead of handling.

Full keel or heavy displacement boats are another case. Many traditional cruisers track beautifully offshore but handle like shopping carts at low speed. Add a narrow marina fairway and some tidal flow, and things get complicated fast. I’ve been at the helm of one such boat during a docking attempt in a tight Pacific Northwest harbor, with a brisk crosswind and an engine idle setting that surged just enough to foil any finesse. The rudder was useless, the reverse was sluggish, and the bow had a mind of its own. That was the day I truly understood the appeal of a bow thruster.

For those without a thruster—or for those who prefer not to rely on one—there are plenty of effective alternatives. Understanding how your boat behaves in reverse, especially in terms of prop walk, can turn what seems like a quirk into an asset. Strategic use of spring lines can let you pivot, pull in, or back out of a slip with surprising elegance. Even the timing of your throttle, the angle of approach, and how you use your momentum all play a role in fine-tuned handling. Some boats are even equipped with stern thrusters, which—while less common—can offer more nuanced control, especially on wide transoms. And of course, no substitute exists for a well-briefed crew. Good communication and practiced line-handling will always trump button-pushing when things go sideways.

So, what’s the final verdict?

For newer skippers learning to handle a boat in crowded conditions, a bow thruster can be a powerful tool. Nice, certainly, but in many cases approaching necessary. For those with limited mobility, small crews, or a tendency to dock in challenging spots, it becomes an even more attractive asset. For skilled sailors who take pride in traditional handling techniques and enjoy the challenge of tight quarters, a bow thruster is still just nice. Something to appreciate when it’s there, but not something you’d miss.

For us, a bow thruster remains squarely on the nice list. The price tag associated with the installation of a new bow thruster, for most, is extremely prohibitive. You can buy a small but capable near shore sailboat for the price of a bow thruster installation! Prudent seamanship means always having a plan A and plans B, C, or even D when it comes to docking. Success lies in recognizing the variables at play during each docking situation and preparing corresponding strategies in advance. Equally important is truly understanding how your boat handles. Dedicated sessions to hone close-quarters maneuvering, learning to use prop walk to your advantage, and practicing various approach techniques is time well spent, and often the difference between a smooth landing and a catastrophic one.

If you’ve got a bow thruster, there’s no shame in using it. And if you don’t, enjoy the quiet satisfaction of gliding gently into that slip without it—until you’re wedging into the last available space in Ganges with 15 knots on the beam and a boatload of witnesses.

Gio and Julie of Pelagic Blue lead offshore sail training expeditions and teach cruising skills classes aimed at preparing aspiring cruisers for safe, self-sufficient cruising on their own boats. Details and sailing schedule can be found at www.pelagicbluecruising.com.