Perhaps the greatest source of fear for boaters on the B.C. coast are the currents of the many passes one must navigate.

The idea of your vessel being swept along by the power of a pass’s unstoppable hydrodynamic force can be a little intimidating. However, passes can lead to greater things—from secluded anchorages to significant shortcuts to your destination—and transiting a pass can be its own reward.

Passes are as changeable as the weather. This is not surprising when you consider how tidal currents are created by a complex interaction of the moon and sun, as well as the local topography and bathymetry. You soon learn that a pass transited on a calm day can be decidedly different on another day when a strong wind is blowing. For example, Porlier Pass between Galiano Island and Valdes Island turns into quite a monster if, during a large flood, a south-easterly gale comes up.

In this article, we’ll examine the major passes of the Gulf Islands—from Active Pass in the south to Dodd Narrows up north near Nanaimo—with the hope that your next transit will be a pleasant one. Be sure to have all nautical charts as well as Canadian Hydrographic Services (CHS) tide tables and Sailing Directions for this area. Tide tables and Sailing Directions are free online at:

charts.gc.ca/publications/tables-eng.html.

Boundary Pass

This strip of water straddles the Canada-U.S. border and marks the eastern entrance to Haro Strait, which separates the Canadian Gulf Islands from the American San Juan Islands to the south. It is not an especially tricky pass as long as the wind is not too strong against the current. When it is, the pass can be choppy.

Boundary Pass is also part of the main shipping route, so it’s prudent to cross at right angles and make the transit as quickly as possible if traveling to or from American waters. Westbound ships rounding East Point can quickly be on a collision course with you.

Although Boundary Pass is wide—over 2.5 miles—currents can exceed 5 knots south of Saturna Island. During a strong flood, tide rips and overfalls form at the north end of Patos Island and tremendous turbulence often forms from Tumbo Island to East Point on Saturna Island. This is the main turning point for flood currents flowing into the Strait of Georgia from Haro Strait and often creates a large eddy extending to Active Pass. When wind is against the tide, steep seas will form south and east of East Point. During an ebb, the current sets onto this reef, as the captain of the barque Rosenfeld discovered in 1886 when his vessel, in tow from Nanaimo, ran on the rock now bearing the ship’s name. As the Sailing Directions notes, ebb currents run in surges that form eddies; the flood, however, runs more evenly.

Killer whales are frequently sighted in the waters off East Point and Pacific white-sided dolphins have escorted us when crossing Boundary Pass. Boaters must observe the Interim Sanctuary Zone around East Point. On our last cruise from Sucia Island in April last year, two humpback whales followed us to the north end of Patos Island.

Further west along Haro Strait, the currents diminish to about three knots on spring tides but flood currents can be strong along the south side of Pender Island to Tilly Point.

Active Pass

This S-shaped channel between Galiano Island and Mayne Island is the main pass for commercial and recreational vessels heading in and out of the Gulf Islands, and its transit is complicated by the regular arrival of large, wave-generating car ferries. These BC Ferries, often traveling at speeds in excess of 10 knots, can kick up a lot of wash and must always be given the right of way. Some pleasure boaters avoid Active Pass because of the ferry traffic, but they are missing a beautiful channel abundant with wildlife, towering bluffs, and impressive hydraulics. It is also a forgiving pass in the sense that currents aren’t excessive for small boats and there are often ways to work the eddies if you have missed slack.

This S-shaped channel between Galiano Island and Mayne Island is the main pass for commercial and recreational vessels heading in and out of the Gulf Islands, and its transit is complicated by the regular arrival of large, wave-generating car ferries. These BC Ferries, often traveling at speeds in excess of 10 knots, can kick up a lot of wash and must always be given the right of way. Some pleasure boaters avoid Active Pass because of the ferry traffic, but they are missing a beautiful channel abundant with wildlife, towering bluffs, and impressive hydraulics. It is also a forgiving pass in the sense that currents aren’t excessive for small boats and there are often ways to work the eddies if you have missed slack.

However, Active Pass remains a challenging stretch of water and requires a skipper to be on full alert from beginning to end. Ferry traffic is almost constant and emerges quickly around points of land concealing the bends in the pass, and the recreational boater should never obstruct or impede the course of a ferry. You can monitor their movements on VHF and AIS. Ferries normally announce their arrival at Active Pass on Channel 16 but it’s a good idea to contact Victoria Traffic on Channel 11 to receive details.

Heading west or inbound (coming from the Strait of Georgia), you can motor between Fairway Bank and the green can buoy at the south end of Gossip Shoals or enter near Georgina Point if that side of the pass is clear of ferry traffic. If we have missed slack, we’ll make our way along an eddy to Mary Anne Point. Once around this point, we are normally able to make our way through the pass, keeping to the Galiano Island side. However, if strong current at Matthews Point is too much for our sailboat, we’ll cross over to Lord Point on Mayne Island and work our way close along the Mayne Island shore toward the kelp bed east of Helen Point, and then cross back to the Galiano side to exit the pass. If the current is too strong for your boat to complete this maneuver, you can cross over to the Mayne Island side at Mary Anne Point and wait in Naylor Bay or Miners Bay for slack.

The area from Helen Point to Collinson Point is where the current is strongest on a flood (up to 7 knots on the Mayne Island side) and where you may be tempted to turn up the engine revs to get free. If it looks dicey or the current appears to be too strong, you can turn around and drift back into Georgeson Bay to wait for the current to slacken. Be absolutely sure to stay clear of the reef marked with a green quick flashing beacon near Collinson Point and do not, on a flood, position yourself in front of it until well out of the pass.

The flood stream pushes a pronounced tongue of water into the pass and you can see currents gain speed east of Helen Point. The stream makes a beeline to the bluffs on the opposite shore where it turns 90 degrees southeast. When this stream combines with ferry wash, tremendous overfalls and rips form in the area west of Matthews Point and can reach strengths that generate a dangerous standing wave.

Ebb current is generally less turbulent, although ferry wash will continue to be a problem for small recreational boats throughout the pass. Generally, rips are not as bad during ebbs.

If you don’t want to transit Active Pass after a late-evening crossing of the Strait of Georgia or need a spot to wait for slack water, there is a usable anchorage in Whaler Bay just inside the reefs at Cain Point. Miners Bay is another possible overnight location, either at anchor or at the government dock (both of which will be bumpy).

Porlier Pass

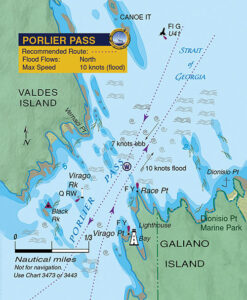

The largest gate pass (meaning short and fast) south of Seymour Narrows, with currents reaching 10 knots, Porlier Pass is potentially the most dangerous of all the Gulf Islands passes. Currents here can generate large whirlpools and overfalls—from Race Point to the reef opposite Dionisio Point—and these are especially hazardous if current is flowing against strong easterly winds. On big floods, the view of the water pushing against the rocky west shore of Race Point is impressive. In addition to currents, turbulence from numerous shoals and reefs within the pass can make the seas in the pass dangerous in strong south winds.

The largest gate pass (meaning short and fast) south of Seymour Narrows, with currents reaching 10 knots, Porlier Pass is potentially the most dangerous of all the Gulf Islands passes. Currents here can generate large whirlpools and overfalls—from Race Point to the reef opposite Dionisio Point—and these are especially hazardous if current is flowing against strong easterly winds. On big floods, the view of the water pushing against the rocky west shore of Race Point is impressive. In addition to currents, turbulence from numerous shoals and reefs within the pass can make the seas in the pass dangerous in strong south winds.

If you miss slack water, and the tide is not too large, you can usually work your way through Porlier Pass by staying parallel with the current and steering as close to the middle of the pass as possible. If westbound, we arrive within a quarter- to a half-mile southeast of the green flashing buoy at the north entrance. Lining up this buoy with the light at Race Point allows us a course through the deep water of the pass and out of danger of the rocks off Valdes Island. Once we are about one cable or about an eighth-of-a-mile off Race Point, we take a middle route through the pass between Virago Rock and Virago Point. There is a Q RW (quick-flashing light that is red or white, depending on your angle of approach) sector light on Virago Rock for night transits and we stay in the middle of the pass until clear of the light. Be aware there can be strong turbulence off Romulus Reef and there’s a north set towards the reef extending from Black Rock in floods. It is essential to maintain your bearings, especially at night, to ensure you are clearing these dangers.

Interestingly, the maximum current for the pass at flood (10 knots), is 40 percent stronger than the ebb (7 knots). The stream, in either direction, is a fairly straight and short run, with two major deflections caused by the island topography and numerous reefs. The main danger when transiting Porlier Pass is being swept onto reefs at the east and west ends of the pass. Boaters sometimes steer a little too close to Galiano Island and find they are being set onto the reef extending from Dionisio Bay where depths at low water can be just a few feet. The area northeast of this shoal water can be very dangerous in gale conditions and is where some of the Strait of Georgia’s roughest and largest seas can occur.

One of the main drawbacks of Porlier Pass is the lack of shelter on the Strait of Georgia side for vessels waiting for slack. Dionisio Bay, a marine park at the north end of Galiano Island, provides some shelter in south winds but is quite open to the north. This bay however makes for a good temporary stop in settled weather, with good holding in sand and mud, and a chance to visit the sandy shell beaches of Dionisio Marine Park. The park has a rich history, as evidenced in the shell middens that make up the beach and date back more than 3,000 years. Archaeologists have determined the Penelakut First Nation used this beach extensively.

Tugs and barges often use Porlier Pass and you can obtain information on their movements by listening to Channel 11, Victoria Traffic. Tug operators can usually be contacted directly on Channel 16.

Gabriola Passage

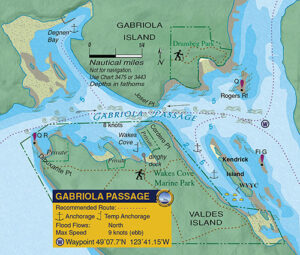

Few passes along the entire B.C. coast are as straightforward as Gabriola Passage. This pass is a yes/no situation and either your boat has the guts to buck the current or it doesn’t, because in a slow-moving sailboat there is no chance to wiggle through if you arrive late.

Few passes along the entire B.C. coast are as straightforward as Gabriola Passage. This pass is a yes/no situation and either your boat has the guts to buck the current or it doesn’t, because in a slow-moving sailboat there is no chance to wiggle through if you arrive late.

In the 1950s, Canadian Hydrographic Service field workers were using baby bottles with flashlights inside to measure nighttime currents at Gabriola Passage. The bottles were cast out by fishing rods from shore and as they gained speed and, were swept through the pass, the workers would take transits on the lights and reel the bottles back to shore. By the 1970s, field workers were experimenting with fixed pods on boats to measure current. As a result of study and analysis done in 1979, daily tables were introduced for Gabriola Passage, starting with the 1987 edition of the Tide and Current Tables. (Prior to this, predictions for Gabriola were based on Active Pass.)

Gabriola Passage is a straight-line stream with the main turbulence occurring on a flood, starting at the pass and extending to Rogers Reef. Some turbulence can also be expected around the reef near Dibuxante Point. Current in this pass can attain over 8 knots on both flood and ebb. The danger at the west end is near the light beacon off Dibuxante Point where a vessel can get swept onto this reef in either tide direction. You can wait out the tide behind Kendrick Island if bucking a flood or in Wakes Cove if fighting an ebb. The reefs at the south end of Degnen Bay can generate impressive whirlpools and should be given plenty of room.

Dodd Narrows

This short pass, with no submerged hazards and a straight-line stream, presents few problems except those created by other boaters. Because this pass is very narrow (often with fast streams and no room to work the eddies) it is susceptible to wash from fast-moving power boats which, when bucking the current, can trigger large standing waves capable of swamping smaller craft. When the pass is busy, as it often is in summer, slower vessels may want to stand off a short distance to check for oncoming powerboat traffic.

A flood current pushing into Northumberland Channel against a strong summer northwester can result in significant chop for a few miles north of the pass. Also, there can be strong turbulence on ebbs just east of Joan Point. Maximum currents in the pass are in the 8- to 9-knot range.

Nearby lies one of the great temptations in passes—False Narrows. This is a pretty pass, in a dinghy. We haven’t mustered the courage to go through in a sailboat. With streams easily 4 knots, shoal water, kelp and numerous reefs, this is obviously not a safe pass and best left to the locals who know it well.

The information in this article and for other passes on the B.C. coast is included in Best Anchorages of the Inside Passage by Anne Vipond and William Kelly. It is now in its 2nd revised edition and is available at bookstores, chandleries, and online.