Voyaging and Survival Philosophy

From the December 2020 issue of 48° North.

Steve Callahan has spent his life around boats — sailing, voyaging, building, designing, and writing about it. He is best known for surviving 76 days alone in a life raft when his sailboat was lost in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. He wrote the best selling book, Adrift: 76 Days Lost at Sea, about that experience. The following continues from an interview started in the November 2020 issue of 48° North.

48° North: Even though you don’t live here in the Pacific Northwest, one of your many connections to the area is a special friendship with a giant in our regional scene, Port Townsend boat builder and innovator, Russell Brown. Please tell us your relationship with him.

Steve: Russell is a little younger than I am. I read about him first in Multihulls magazine. I had built a 28-foot trimaran back in 1974, and my first wife and I lived on board for a while. Multihulls being desperate for stories at the time, they published a little article about us. There was another article around the same time about this young man, Russell Brown, who had built this 30-foot plywood box proa and sailed it off.

Another friend had already gotten me very interested in proas. After Adrift, which is what most people know me for — being dumb enough to lose my boat in the middle of the Atlantic and bob for two-and-a-half months across half of it in a life raft — I hooked up with Roger Hatfield who was running Gold Coast Yachts in the Carribean. He gave me Russell’s information, and I looked him up. At that time, Russell was building his third proa. We got to know each other, and got to be friends, fortunately for me. He’s a great guy and incredibly talented.

He’d sail near where I live in the summer and people would go, “Hey did you see that spaceship landed down on the beach.” Multihulls in general were thought to be pretty weird craft in those days.

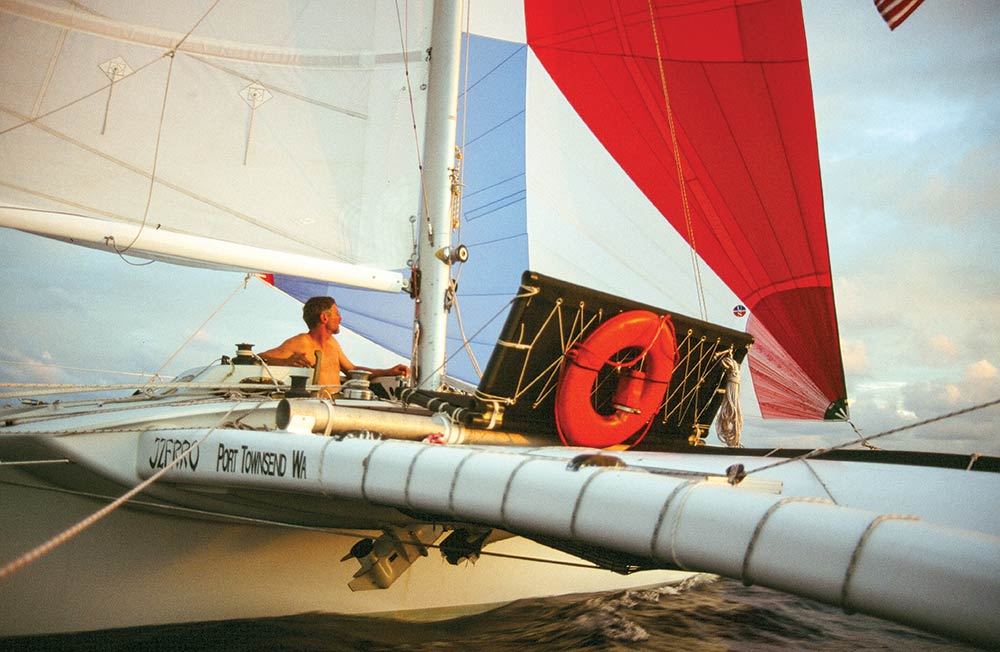

I did some sailing with him through the years, and one of the best voyages I ever made was when he called me up after he built his last Jzerro and said, “Well, I’m thinking about sailing across the Pacific. Do you want to go with me to Tahiti?” It really was one of the great adventures of my life. He downplays all this stuff, but it was a remarkable voyage by an incredible sailor.

Can you give us a few more details about that voyage to Tahiti?

When I was 11 or 12 years old and first learning how to sail, I was taken with it completely. While other boys were interested in cars and other things, I was trying to teach myself the rudiments of boat design, celestial navigation, and my afterschool job was helping my dentist build a 40-foot trimaran. A couple of the books that had an immense impact on me were: Robert Manry’s Tinkerbelle, in which he took a 13-and-a-half foot sloop across the Atlantic; and John Guzzwell’s Trekka Around the World; as well as Kon Tiki. They were all small boats. Trekka was 21 feet, about the size of Napoleon Solo, the boat I lost in the Atlantic. I was awed, thinking, ‘You can have a life of adventure and you don’t have to be specially talented, you don’t have to be rich.’ My father was an architect, and I was interested in an efficient use of space. I think boats are incredible human creations that combine dwelling with vehicle with art.

With all that in mind, something really attracted me to the proa — they were so simple. You’re going back to the rudiments of efficient sailing. I love that virtually all other boat types build up forces the harder you sail them — monohulls and especially multihulls — with righting moment building up quickly. The proa is kind of the opposite. It starts with maximum stability. People worry that they’re tippy, but I found that they’re incredibly stable. In fact, a lot of the time, you were trying to lighten up the ama to keep it riding kind of light on the ocean.

Russell’s proa was a 37-foot 2-ton sailing canoe. On board, you’re living really simply, so close to the water. We had a GPS and a compass that we virtually never used — we were sailing to the wind and the waves and the stars. It just gets back to the roots of who I wanted to be as a sailor. The boat was just incredibly fun and incredibly interesting. We weren’t pushing it to make records — I think we averaged only about 150 miles per day. We’d slow the boat way down at night and get some rest.

Russell grew up on boats, and one thing he said to me was, “I’m really glad I grew up playing on the ocean.” Even when there were big waves, he had a surfer’s attitude toward the sea. You’re not fighting it all the time. Just like Kon Tiki was more about being there than about getting someplace. I always found raft voyages kind of appealing. Little did I know, I was going to do a little bit of a repeat of my own.

Getting back to Jzerro, it’s almost full circle, because it’s ancient technology, but Russell brought it forward into the 21st century by building this incredible boat with modern materials — lots of little carbon bits and pieces. What Michaelangelo was to marble, Russel Brown is to composites. It’s a little strange out there in Port Townsend, the land of traditional boat building; but there’s a place for everything.

I want to return to some of your experience and lessons from surviving adrift on the raft. I often think of offshore sailing as a series of repairs and/or preventative measures, with a little sailing and even less sleep mixed in. On the raft, how did you find the balance of the projects that you were working on and waiting time. And how did that change over time?

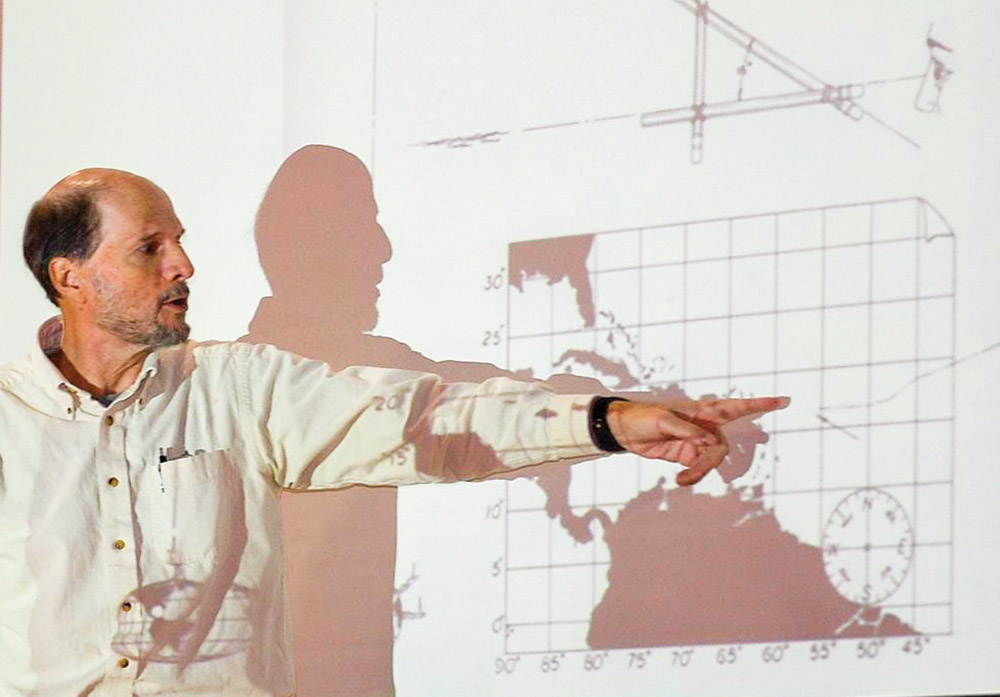

It changes in very fundamental ways over time. Through Adrift, I’ve been lucky to get involved with survivors of all kinds of things. Traveling around the world for conferences and events with survival experts, I’ve gotten to meet a film crew that crashed into a volcano, people buried in avalanches, and people held hostage. Everybody has their own model, none of them are universal, and I developed my own. I refer to that process as the Stages of Survival, and mine runs more or less chronologically.

There’s the pre-impact — the preparation for disaster and whether you are prepared or not. Then there’s the impact itself — that immediate time when the boat’s holed or I’ve got to run out of this burning building or whatever — and that has its own set of issues. Then there’s a period of recoil, and I call it disorientation and fear; and that is, ‘OK, I’ve bailed out now, but all the old rules of my life have gone away. Everything I thought was normal is gone. How do I make a living in this new situation I’m in?’ And that can be difficult to get through. A lot of people get through bailing out, only to die in that really difficult period of recoil, which is before you reach the stage of adaptation: where you’ve figured out, “I’ve recreated my life here.”

It does vary in time, especially with the equipment. At first, it’s just figuring out the equipment — how does it work? What are the problems? How can I deal with the most immediate problems? What are the priorities? Am I seriously injured (which you can’t do much about if you’re in a life raft, unfortunately)? Can I avoid or recover from hypothermia (which is a really huge problem for survivors)? All those things can kill you in moments to minutes.

Then, you get into long-term things. You start thinking about water before you start thinking about food. You might live a week to ten days without water. You can live up to a month without food.

I was constantly prioritizing, asking “What needs the most attention today?” I needed to pump up the raft every day. As the raft gets more worn, it leaks more. Then you have a lot of gear that gets damaged, as you say. I had a little spear gun, almost like a toy, that was responsible for getting almost all my food. I was catching mahi-mahi (also called dolphin fish or dorado). They’re big and powerful, so they were constantly breaking this spear gun, and I’d have to tie it back together. I was always thinking about how to make a repair in a way that also rationed my gear. The physical part of me wanted to catch every fish I could, all the time, but it wasn’t practical, because I didn’t know how long I’m going to be out here, I’m endangering my equipment, I’m fishing with a spear stuck through a big, powerful fish as it swims around my inflatable raft in the middle of the Atlantic. You’ve got no backup at that point, so it’s a balance.

By the time I got through the recoil stage, which was pretty difficult, then I started getting into adaptation — I began to catch fish, and I figured out how to use the solar stills (because they didn’t work the way they were supposed to). Of course, I was managing my use of energy and loss of water from sweating, as well as trying to keep myself warm at night.

Sailing, especially offshore sailing, is like you describe. I tell people, “At sea, Murphy’s Law is quite optimistic. Not only anything that can go wrong will go wrong, but even the things that can’t possibly go wrong are going to find some way to screw you.” I found that gratifying throughout my life. I always loved wilderness environments where you’re constantly confronted with solving problems in an isolated environment with limited resources, and where things are used outside their normalized context.

I’ve talked to some people who were on a plane that was down on the way to the Bahamas. They went drifting off in just life jackets and whatever they had in their pockets. Two guys were looking at stuff in their wallet, and they found credit cards that were shiny in the moonlight. The next day, they were able to signal an aircraft with their credit cards, which were useless in their original purpose, but were shiny waterproof surfaces. In the film Apollo 13, there’s a brilliant scene in which the crew have to figure out how to make a CO2 scrubber out of what they actually have on the spacecraft. All the engineers go, “I don’t know, it’s not designed to do that.” And the guy on the ship goes, “Forget about what it was designed to do, I want to know what it can do.” I think that applies well to sailing. When you go offshore, you have total freedom but you also have total responsibility. I find the two completely linked.

It’s the case with people too. I love that about voyaging. It doesn’t matter what your position was ashore or how rich you are. What matters is whether you show up on watch early, whether you can adjust to your surroundings, and that you are there to give a helping hand if it’s needed. That adaptability is a trait in all the good sailors that I know. There’s nothing rigid in sailing. You have to work with the ever changing variables in such a way that you can’t live by one rule or you’ll fail.

It makes sense that it is even more important in survival settings, which is really life on steroids. One person’s trauma is a walk in the park to somebody else. Some people thrive on difficulty. Other people just don’t know how to deal with it.

Among the survivors that you’ve gotten to know over the years, are they all the type who thrive under difficulty?

I don’t know if I can say that, because we all have a limit; none of us gets out of here alive. Sometimes, there are people I consider accidental survivors — people come in and swoop them out of the predicament that they’ve found themselves in. And then there are people like me, who don’t have a choice — if you’re going to live, you’d better do something about it. It’s just like the saying, “Heroes aren’t anything special. They are just given a set of circumstances and they step up to the plate.”

To me, denial is the number one enemy of the survivor. That’s why a lot of people perish in those early stages. I can’t tell you how overwhelming it is. I beat myself up really badly the first two weeks. “Why am I here? Why did I do this? Why didn’t I make Napoleon Solo a better boat? Why was I so terrible at relationships? Why did I have a failed marriage? Why didn’t I make any money?” You go through the litany of every failure in your life. It can be incredibly depressing.

Hope and the will to survive are things you build. There is hope that’s wishful thinking, but that’s not really a functional hope. We create realistic hope by working at it, by chipping away at a problem. You go, “OK, maybe this didn’t work, maybe that didn’t work, but I learned something from that failure.” When Edison was doing the lightbulb, people would ask him, “You did 10,000 experiments, how do you feel about all those failures?” And he said, “I have not failed. I have just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” It’s all a learning experience, and you have to be patient with yourself, which is a skill set of its own.

A lot of people look at Adrift, and they look at me or other survivors and they think that we’re heroes. I want to emphasize this: it’s not true. We’re all regular people. To me, Adrift is almost like a confessional. The hero of the story is the sea and the incredible natural world we live in. And the dorado! They were my primary food source. They threatened me, almost killed me at one point, actually. I knew many as individuals. And in the end, they brought my salvation, because the ecosystem that they helped create around the raft drew birds to the raft. Local fishermen came out because they knew these birds are a sign that something else is going on in the water. They came out to find fish, and they found me in the middle of it. I was the clumsy human observer of this incredible world we all love.

As the years have passed now, especially given the role the ocean played for you, as the hero in your story, can you describe your relationship to the ocean and how it has evolved since you were Adrift?

It varies, even on an individual voyage. If I go off on an offshore trip, Bermuda is almost too short. It takes me a few days to get back into the rhythm. For a few days I’m sitting there wondering what the hell I was doing — I don’t need this, it’s cold, it’s bouncy, it’s uncomfortable. But, you get into it, and that’s been true of a lot of things I’ve done.

We can have this love/hate relationship with our lives and our environments. Going through it all, you find incredible gifts you could never find in any other way. Being adrift taught me a lot about myself, and that’s a very common feeling among survivors. I don’t know of any survivors I’ve met that regret having that experience. Not one of us wants to go back into it. They are, by definition, sort of hellish experiences. But there’s a great deal of value in that too. Building a boat, sailing a boat, building a house, having a baby — everything that is really worthwhile is a challenge. I find that fulfillment is in a direct relationship with struggle.

That’s the way it is with me and voyaging. I don’t expect it to be like bobbing around the bay having a cold beer — that’s not why we do it. We go off because it’s an incredibly unique and beautiful environment where we are the small players. We are privileged to have a little taste of that. It’s my whole approach to life, and certainly sailing.

Joe Cline

Joe Cline has been the Managing Editor of 48° North since 2014. From his career to his volunteer leadership in the marine industry, from racing sailboats large and small to his discovery of Pacific Northwest cruising —Joe is as sail-smitten as they come. Joe and his wife, Kaylin, have welcomed a couple of beautiful kiddos in the last few years, and he is enjoying fatherhood while still finding time to make a little music and even occasionally go sailing.