Living Aboard a Flicka

From the May 2019 issue of 48° North.

The Pacific Seacraft Flicka 20 has a reputation as a well built, good sailing, bluewater sailboat. Most sailors will be familiar with the design. In spite of, or perhaps because of this familiarity, when other boaters learn that I live on a 1985 Pacific Seacraft Flicka 20 called Sampaguita, they tend to raise their eyebrows. For the record, it’s not a stunt.

I’ve recently been reflecting on and writing about why I bought Sampaguita, and also why I live aboard what nearly everyone considers a very small boat. I think my philosophy and style will resonate with some people, and not just sailors. But I also suspect that others will consider me an antisocial plebeian masochist. If you are curious about which group you belong to, read on.

When I decided to purchase and live on a bare-bones, 28-year-old Flicka 20 in 2013, I considered it a necessity. No one forced me to buy a boat, but with personal goals of solo sailing expeditions, I felt that it was part of the bigger plan. I also felt that the only fiscally responsible option was to live aboard and forgo the costs of living on land. The experienced sailor knows that the bigger the boat is, the more time and money it takes. I knew liveaboard neighbors with much bigger boats who found it difficult to reach escape velocity because they got stuck in the transition from home to boat. Others never left the dock, either because they never intended to, or couldn’t afford to keep their boats seaworthy. Some owners maintained their boats well but rarely used them. With all of this in mind, I bought the smallest boat that would accommodate my aspirations.

I have begun to achieve those sailing goals and have sailed Sampaguita around the Pacific Northwest, with 275 days of sea time in six years. Most of my expeditions have been single-handed and have included trips to Princess Louisa Inlet, up the outside of Vancouver Island to Hot Springs Cove, and throughout the San Juans, Gulf Islands, and the Sunshine Coast. In May and June 2018, I completed a 39-day counter-clockwise solo circumnavigation of Vancouver Island.

It is not, however, the cruising that confounds most sailors. It’s the living. Once the decision to live aboard Sampaguita was settled, the question became, “how do I manage this?” Through determination, the adaptability of the human race, and by embracing the proverb “necessity is the mother of invention,” I have developed systems and adjusted my lifestyle to make it happen. Don’t think that I have discovered the secret to a blissful life, or that I started with all the best answers, or have them today. It has been a learning process from the beginning. Like so many things in life, it is about attitude. If you are determined, keep a positive mind, and accept the sacrifices and challenges as a fun part of the adventure, then it just becomes a thing you do. Honestly, I don’t feel like living on the Flicka is any harder than on land. It’s just different.

It is not, however, the cruising that confounds most sailors. It’s the living. Once the decision to live aboard Sampaguita was settled, the question became, “how do I manage this?” Through determination, the adaptability of the human race, and by embracing the proverb “necessity is the mother of invention,” I have developed systems and adjusted my lifestyle to make it happen. Don’t think that I have discovered the secret to a blissful life, or that I started with all the best answers, or have them today. It has been a learning process from the beginning. Like so many things in life, it is about attitude. If you are determined, keep a positive mind, and accept the sacrifices and challenges as a fun part of the adventure, then it just becomes a thing you do. Honestly, I don’t feel like living on the Flicka is any harder than on land. It’s just different.

The first thing that drives my quality of life aligns with the old real estate adage, “location, location, location.” I have been fortunate to have a marina that allows me to live on a 20-foot boat. This is not the case everywhere, and securing a liveaboard slip in a place you wish to live can be a massive hurdle. When I bought Sampaguita, I already owned and lived aboard a Columbia 26, and was able to keep the slip it was in. This was key. My commute has since changed, but this location was a short walk from my place of employment, and it is within walking distance of many services and grocers. In these ways, it was far better than many land-living options.

While in port, my galley set-up revolves around an electric hotplate and kettle. These require AC shore power. I am not a “foodie,” so I don’t miss extravagant meals. I have learned to select meals that are simple to prepare, nutritious and, for me, interesting enough. My diet typically consists of a mix of fresh and minimally processed foods, like vegetables, beans, and nuts. My physician approves. It is an easy trap for a liveaboard to fall into “restaurant living,” but this is usually both unhealthy and very expensive. Ironically, I eat better when I’m trying to economize and purchase all of my foods through a grocer. When away from port, I use a 2-burner propane set-up to achieve similar results.

With only one sink and space at a premium, I keep a limited amount of kitchenware. I use the electric kettle in port for heating water, the propane stove and a saucepan are used while away. These work if I need hot water for food prep or washing dishes. As a rule, I avoid oily and sticky foods. The sink uses a hand pump which has its challenges. The silver lining is that it regulates water use well.

For freshwater, I have an integral 20-gallon tank which I use for washing dishes and my hands, and for brushing my teeth (for the last, I put that into a bottle and empty it on shore regularly). The water tank requires refilling every 10 to 30 days, obviously dependent on use. I have dockside access, so refilling has been a simple procedure. For drinking water, I have several jugs which I fill and filter, and also use it for cooking, or whenever I need more than is easily pumped from the tank by hand. I store these jugs in a large bin designated for this purpose. I also have full spares stowed around the boat for emergencies.

Refrigeration is not a problem during the winter months. The ambient air temperature works well for what I need. Summertime requires a different approach. I have an ice chest, but keeping up on ice becomes a chore, and doesn’t feel sustainable. At one time I had a walk-in freezer available to me, and I could freeze half-gallon milk jugs full of water. These worked great, but they were heavy, and that opportunity has come to pass. People have mentioned dry ice, and I may give that a go to see if that is practical, but for now, I work with the seasons and shop accordingly. Frozen food storage is typically something that is out of my wheelhouse. Items such as fresh milk, which I use for tea and occasionally cooking, will keep well in the winter season and parts of the spring and fall. As the temperatures warm, I fall back on powdered milk.

I have an electric heater for cold nights, but honestly, I hardly use it. I’m originally from central New York, so Seattle doesn’t really feel that cold to me. I bundle up instead. The electric heater can certainly heat the space adequately, but if I want to keep air circulation and ventilation, which I do, the heat escapes very quickly. If I seal up the boat and run the heater, condensation quickly becomes an issue. Any boater knows this leads to mold and mildew. Since I prefer fresh air to that, I tend to opt out of the heater.

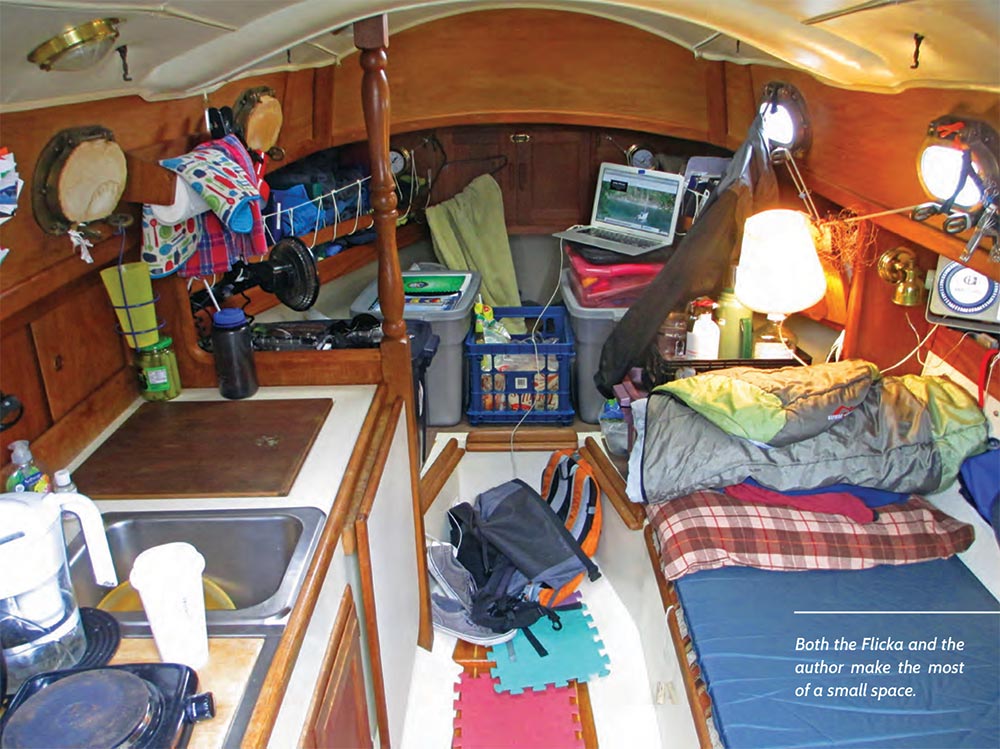

I slept in the v-berth for the first five years but changed to the settee about 18 months ago. This arrangement is easier to use and commits less space to sleeping and more to waking life. I have used sleeping bags the entire time, regardless of where; this is simple and provides plenty of warmth. In the morning, I just roll it up. I’ve removed the cushions from the v-berth, and it now accommodates other systems. The water and kitchenware bins are stored there. The toiletries, miscellaneous, and food storage bins too. The laundry bag lives in the forepeak, and there are many small spaces for other items, such as the bike helmet. The bin system worked well on the Vancouver Island circumnavigation. It kept the boat tidy, and the bins locked together very well, restricting movement in the rolling and choppy seas.

Since the boat is small, I have an inner slip, which put me a stone’s throw from the shore-side facilities including heads, showers, and laundry. Since neither the Columbia nor the Flicka came with an enclosed head, this has been an important feature. I streamline my human waste with that of the shore population, utilizing the public plumbing infrastructure. When on an expedition, I have learned and adapted camping techniques, which involves bottling and bagging, and disposal on land. For some, this is a tough concept to wrap their head around, but if you think about it, that is what every boater does with a holding tank and pump-out station. My version is just more personal, less expensive, more easily controls odors, and uses simpler machinery with fewer points of potential failure.

Since the boat is small, I have an inner slip, which put me a stone’s throw from the shore-side facilities including heads, showers, and laundry. Since neither the Columbia nor the Flicka came with an enclosed head, this has been an important feature. I streamline my human waste with that of the shore population, utilizing the public plumbing infrastructure. When on an expedition, I have learned and adapted camping techniques, which involves bottling and bagging, and disposal on land. For some, this is a tough concept to wrap their head around, but if you think about it, that is what every boater does with a holding tank and pump-out station. My version is just more personal, less expensive, more easily controls odors, and uses simpler machinery with fewer points of potential failure.

I have a small storage space I rent for the purposes of items too large for the boat, or too infrequently used. This appears standard for people living aboard boats of almost any size. I am not sure the items I store are worth the cost of the annual fees, but it is convenient. I often reassess the value of what is in there.

That covers much of the “how” I live aboard a Flicka 20 in Seattle. The “why” is about sustainability, both of my lifestyle and in reducing consumption for environmental reasons. It’s about living within my means. It’s about going small and going now (yes, cliché, but powerful). I have aspirations of sailing a small boat across an ocean, so much of this lifestyle is rooted in the training, the development of systems, and the management of the funds necessary to continue sailing. Having realized one of my Northwest goals of circumnavigating Vancouver Island, I feel more able as a sailor to consider an extensive voyage. At the dock or on the water, I emphasize an attitude of minimalism and sacrifice, and an acceptance of the challenges these present. Since experiences thrill me far more than material possessions, this has worked out so far.

Josh Wheeler

Josh Wheeler is an avid writer and sailor who lives aboard on his 20-foot Flicka sailboat. Follow his adventures at sailingwithjosh.com