Prohibition Failed as a Social Experiment While Fueling Advancements in Boat Design and Marine Technology

The same features that attract boaters to the San Juans today—secluded coves, hidden inlets, and lush forests—once made these islands irresistible to smugglers. A century ago, the scenic anchorages of Sucia, the pastoral light station at Stuart Island, and other now-popular cruising destinations set the scene for illegal activities encouraged by a close international border and fast getaway vessels. In the late nineteenth century, contraband included woolens, silks, and opium, all of which could be snuck in duty-free from Canada by boat. People, too, were smuggled after an exclusion act banned Chinese laborers from entering the United States in 1882.

When the National Prohibition Act outlawed the sale of alcoholic beverages in 1920, bootleggers recognized an opportunity for easy profit by smuggling in whiskey and other spirits from British Columbia, where these products were legal. Prohibition lasted until 1933, ushering in an era of remarkable excess and lawlessness, while fueling innovation and ingenuity in boat design and marine technology. During the heyday of the 1920s, the “rum runners” operating in the waters around the San Juan Islands “had the world in the palm of their hands,” recalled the son of a local bootlegger.

Vice in the City

Generally speaking, the United States had always been a nation of drinkers [see, for example, William J. Rorabaugh’s The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition, 1979]. One ad from 1906 showed a girl sharing a beer with her grandpa, suggesting that drinking locally brewed Rainier Beer was a family affair, benefiting children and the elderly alike. Consumption of alcohol soared in the early twentieth century, with some estimates claiming that Americans drank three times what they do today. Attempting to stop this trend, temperance groups such as the Anti-Saloon League waged an effective campaign against “demon rum,” a generic term that applied to all liquor, resulting in the passage of a series of state dry laws and eventually in a national ban.

Advocates pushed Prohibition as a “Noble Experiment” that would strengthen family life mostly by restricting access to drinking establishments and the sale of booze. “The saloon is the most fiendish, corrupt, hell-soaked institution that ever crawled out of the slime of the eternal pit,” preached Reverend Mark Matthews, pastor of Seattle’s First Presbyterian Church. “It is the open sore of this land.” Some historians now view the temperance movement and dry laws as a way to clamp down on the working class, who, it was feared, might lose productivity if laborers spent too much time in saloons, and on immigrants whose culture and heritage sometimes promoted consumption of alcohol (German beer halls, for instance).

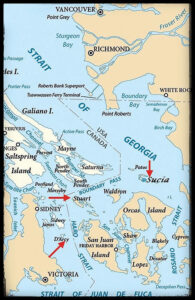

where the ill-fated rum runner Beryl G drifted in 1924. (Right) Cruising past the Turn Point Light Station on Stuart Island today is an invitation to remember this region’s wild and sometimes grim history during Prohibition.

Temperance campaigns targeted cities like Seattle, which had flourished after the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-1898. Rapid growth and prosperity during the early twentieth century brought taverns, cigar stores, dancing halls, and gambling parlors to the downtown area, particularly south of Yesler Way. A 500-room brothel, reported to be the world’s largest, stood on Beacon Hill, the result of shady permitting allowed by the mayor and city officials.

Washington became a dry state in 1916, and the national ban on alcohol several years later was more restrictive—at least on paper. Yet enforcement proved difficult, as measures were underfunded and Washington residents quickly became disenchanted with the new law in 1920. Many Americans who supported the national ban did not realize that beer would be included. Prohibition did not stop the sale and consumption of liquor; it simply drove it underground. And Seattle was a robust market. Speakeasies requiring secret passwords for entrance seemed to emerge on every corner, replacing the old watering holes and offering drink, dancing, and jazz. The Club Royale in Seattle, which required a special membership card for entry, served its boisterous customers their illegal beer in cups so enormous it became known fondly as the “Bucket of Blood.”

Speed Boats, Mother Ships, and Illegal Booze

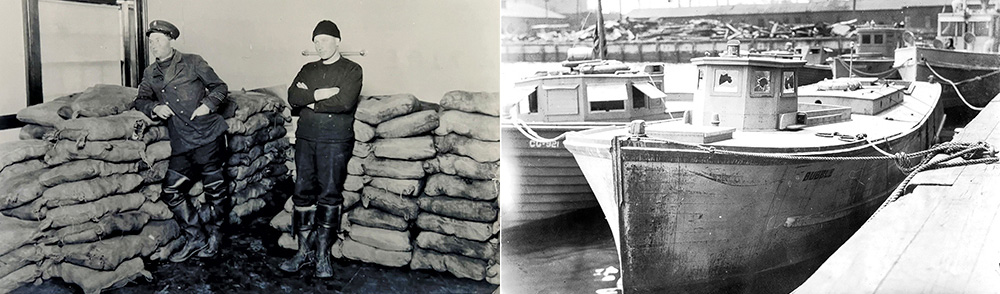

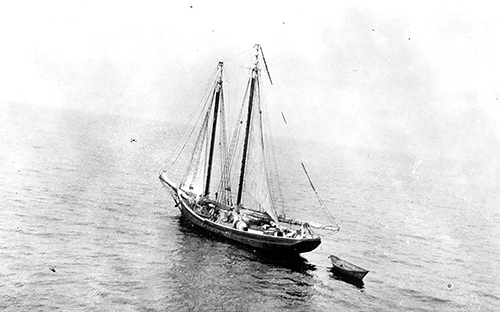

The demand for alcohol in the cities of Puget Sound could not have been met were it not for the rum runners that brought the contraband south from B.C. With nicknames like Legitimate Pete, Uncle Slug, and Pirate Jack, these bootlegging entrepreneurs quickly figured out how to supply thirsty customers while turning enormous profits. The proximity of the Canadian border made for swift over-water transport, and small, fast rum-running vessels escaped detection by speeding at night and weaving through islands, sometimes during stormy weather. They picked up their illicit cargo at B.C. ports or by visiting larger “mother ships” anchored outside the US boundary.

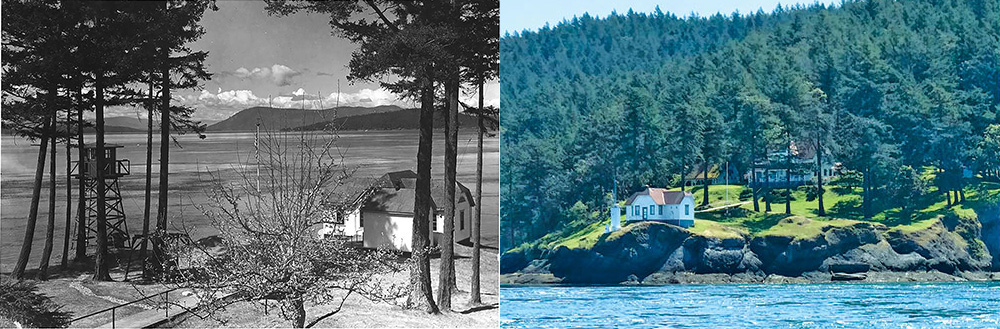

The sparsely populated San Juan Islands with their hidden shorelines provided ideal cover for boats engaged in this activity. Sucia Island, for instance, was a popular drop off point for bottles of illegal booze, which were packed into burlap sacks for transport. Rum runners typically stowed these sacks below in hidden compartments, and sometimes they towed them from the stern, where they could easily be cut adrift if their boat was stopped.

Roy Olmstead, a former Seattle police officer and leading bootlegger, regularly sent his speedboat Zambesie to Haro Strait to collect Canadian liquor at D’Arcy, the southernmost of the Gulf Islands, located west of San Juan Island. This pickup spot was strategic, as D’Arcy was not only surrounded by reefs but also served as a colony for Chinese immigrants afflicted with leprosy, which rarely received visitors or much public scrutiny. Once loaded, the contraband made its way to various distribution points on Puget Sound.

So successful was Olmstead’s smuggling operation that it was said he made more profit in one week than he could have earned in 20 years on the Seattle Police Force. He employed a staggering assortment of people, including boat captains, crews, truck drivers, accountants, and lawyers. He paid off city council members, Mayor Doc Brown, and a large portion of the Seattle Police Department, as his years on the force helped him identify who to approach. Olmstead’s wife Elise (sometimes called “Elsie”) allegedly helped his smuggling business on a radio program, where she was known as “Aunt Vivian.” While reading stories to children, she reportedly sent messages in secret code to Olmstead’s boats as they sought to make deliveries.

Olmstead took pride in the quality of his liquor and counted the Rainier Club, Arctic Club, and aviation pioneer William E. Boeing among his customers, earning him the nickname the “gentleman bootlegger.” A beloved figure, he was also called the “good bootlegger” owing to his refusal to resort to violence even when confronted by hijackers. Olmstead avoided drug trafficking, prostitution, and other illegal activities sometimes associated with bootlegging. Prohibition was unpopular, and Olmstead and many who worked for him believed they were performing a useful, even respectable service.

For all the adventure and glamor, rum running could be dangerous. In 1924, for instance, Chris Waters, the keeper of the Turn Point Light Station on Stuart Island, spotted a boat drifting in Haro Strait. Boarding the vessel, he discovered that the doors and hatches were covered in blood, while multiple bullet holes suggested a struggle. No one was on board but a cap filled with blood confirmed that the crew of the Beryl G had met a gruesome fate. Canadian authorities joined the US Coast Guard in investigating the boat, which had a B.C. registry. Piecing together the evidence, they learned that the owner and his son had been doing business with Tacoma rum runners, who murdered them, ripping open their bodies with a butcher knife so that they would not float. The culprits had hijacked the boat to steal the sacks of liquor on board. Two years later, two of them were hanged in Canada. “The Beryl G murders put the whole rum running trade on edge,” noted historian Rick James [Don’t Ever Tell Nobody Nothin’ No How: The Real Story of West Coast Rum Running, 2018].

A Game of Cat and Mouse

The vessels used in rum running evolved over time. While large boats could transport more cargo, speed and the ability to out-maneuver pursuers, including hijackers and the Coast Guard (charged with enforcing Prohibition on the seas) were highly desirable. Boeing Aircraft influenced the design of fast boats by finding a new use for the light-weight engines once used in combat planes during World War I. Faced with a surplus of these V-12 motors, the company incorporated them into a new line of square-bowed vessels with inverted hulls called “sea sleds” that sold out quickly in the early 1920s. The 12-cylinder aircraft engines were advertised for purchase in local newspapers and boating magazines. Using two of them allowed some boats to approach 40-knot speeds, even when carrying a full load. Boatyards in Vancouver, Victoria, and Seattle filled the growing demand for low-hulled speed boats, while at the same time building the Coast Guard patrol vessels that would pursue them.

During the years of Prohibition, the Coast Guard experienced the largest peacetime fleet expansion in its history. The service sometimes repurposed the rum running boats it seized, using them to pursue smugglers. But its larger vessels were not ideal for chasing and apprehending speed boats. Accordingly, Congress appropriated funds for a new fleet of small boats and an increase in personnel, designed to intercept the rum running trade. During the mid-1920s, a fleet of 75-foot wooden patrol boats were built. Nicknamed “Six-Bitters,” which meant 75 cents, they were equipped with a 1-pounder cannon and other small arms, and could reach speeds of 15 knots. The Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton similarly built 36-foot patrol boats capable of speeds up to 25 knots for the Coast Guard.

Coast Guard patrols were further aided by developments in radio communication. During Prohibition, the radio direction finder (RDF) helped detect lines of bearing on transmissions from mother ships and speed boats. At the same time, rum runners could use RDF to locate the Coast Guard as well. “It was a huge game of cat and mouse,” wrote one Coast Guard source [William H. Thiesen, “The Long Blue Line: Catching the Rumrunners—Coast Guard Adopts New Technology during Prohibition,” 2021].

Coast Guard chases sometimes erupted in gunfire, requiring smugglers to repair bullet holes in their boats. Civilians, too, were drawn into the drama. “Many waterfront residents were jolted awake during that era by the howl of high-powered engines,” John Lund commented, “the peace shattered by cannon fire and the darkness ripped by Coast Guard machine gun tracers and searchlights aiming to uphold the law” [“Rumrunners,” Northwest Yachting 1991].

Photo courtesy of US Coast Guard.

Legacy

In 1933, the 21st amendment repealed Prohibition. No longer profitable, rum running shut down for the most part, signaling the end of an era. “The great parties, the adventure, the big money … these were gone,” observed historian Norman H. Clark [“Roy Olmstead: A Rum Running King on Puget Sound,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 1963].

While the long-term effect of Prohibition on America’s drinking habits is open to debate, the impact on boat design and marine technology is clear. The Coast Guard was better able to meet the challenges of World War II with its advanced fleet of ships and increase in personnel. The growing market in small, fast recreational vessels benefitted from the design of speedsters during Prohibition, and multiple observers claim that hydroplanes evolved from the boats equipped with airplane engines [see, for example, Brad Holden, “Prohibition in the Puget Sound Region (1916-1933),” History Link, 2019].

Today, those cruising in the San Juan Islands can explore the locations important to the rum running trade a century ago. Sucia, for example, offers mooring buoys in multiple bays and coves where illegal booze was once packed into burlap sacks. The light station still stands on Turn Point, where the Stuart Island keeper spotted the ill-fated Beryl G drifting in Haro Strait. Rumors of old rum running boats deteriorating on the shores of San Juan Island persist. D’Arcy Island, located west of San Juan Island, has two new mooring buoys at the site where Olmstead once ran his bootlegging operation. Rum Island and other place names further evoke the smuggling trade, reminding boaters of a time when noble ideals clashed with repressive measures, and a national dilemma played out in our region’s waters.

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor residing in Seattle. She is grateful to the Coast Guard Museum Northwest for providing documents and images.