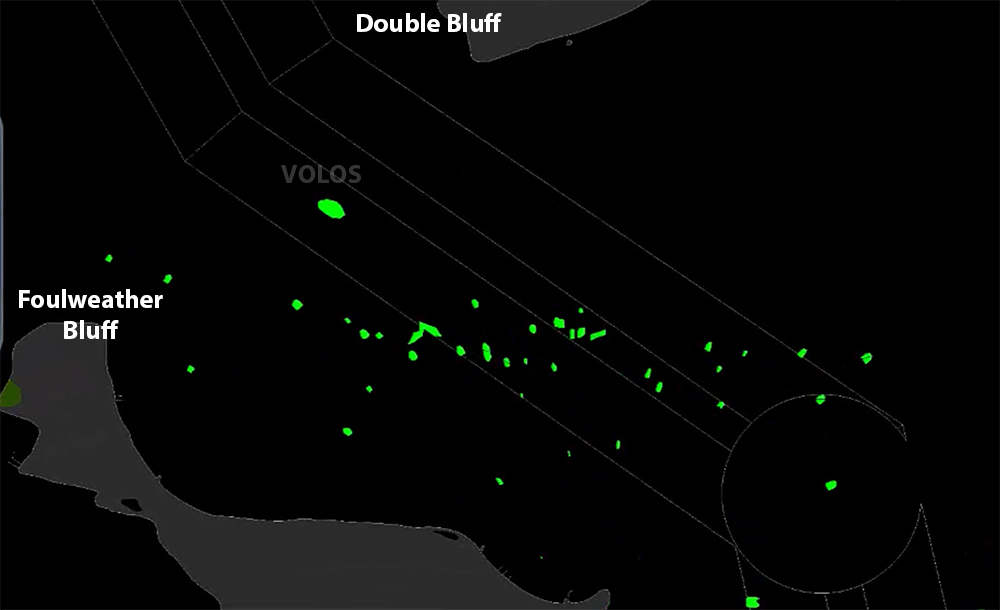

An unusual situation unfolded during Corinthian Yacht Club (CYC) of Edmonds’ annual Foulweather Bluff Race in October 2022. While the fleet was sailing east-southeast between the northernmost turning mark at Foulweather Bluff and Scatchet Head, the pilot of a southbound commercial ship, Volos, in the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) lanes did a 360-degree turn to wait for the racing boats to clear the area. What was originally perceived by some as a gesture of kind accommodation turned out to be a last-resort evasive maneuver, and the pilot submitted a formal report to the Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) which manages the TSS lanes.

This incident carried a variety of direct and indirect risks. First and foremost was the direct risk to sailors’ lives and craft if the ship had continued. Indirectly, the US Coast Guard (USCG) in the area was understandably displeased, and has the ability to limit local sailboat racing by revoking permits or adding new regulations for events that cross or even go near TSS lanes if not satisfied with the recourse to this incident.

The real story here is about the response and resolution, which followed a thorough and thoughtful process, and from which there is much to be learned for anyone involved in sailboat racing in the Pacific Northwest.

CYC Edmonds Foulweather Bluff Race Chair, David Odendahl, was the first to bring this to my attention. At that time, he was in “friendly, yet direct conversation” with Captain Laird Hail, the head of VTS for our region, who indicated that VTS expected CYC Edmonds to take action as the organizing authority (OA) of the event, lest VTS and USCG take actions of their own.

Odendahl quickly involved Eric Rimkus, the US Sailing ARO (Area Race Officer, a local representative for US Sailing), who along with two other US Sailing judges — who happened to be competitors in this race — made up the original protest committee for Foulweather Bluff. The two competing judges recused themselves to avoid conflict of interest as competitors. Given the stakes and the nature of a US Sailing protest hearing in response to an incident involving a commercial vessel, and since Rimkus says he was “tainted” because he already had information that wasn’t included in the protest, he recruited additional US Sailing judges to hear the protest. The judges that created this panel all live outside the area, but crucially, they are in areas where the racing environment is shared with commercial traffic. Among them was Grant Baldwin from San Francisco, who oversaw the proceedings.

There were many parties involved in what Baldwin summed up as, “an unfortunate set of unpredictables.” He mentioned that, “At the outset, not all of the boats had been identified.” In addition to 20 race boat respondents, Captain Hail represented VTS as a witness in the hearing. Baldwin continued, “We conducted a hearing that ran nearly two hours and it was rather exhausting for all concerned.” It took the panel another six days to produce a decision, which relied largely on the International Rules for Preventing Collisions at Sea (IRPCAS) rules of the road.

Baldwin and the panel felt they were “doing a service to the sailors that might yield an unpopular result.” They found that all of the 20 competitors in the hearing had “violated a trio or maybe a quartet of IRPCAS regulations.” Three of the 20 respondents voluntarily retired, an action that Baldwin and Rimkus commended, and the other 17 were disqualified.

As one might expect, there was disappointment and some disagreement from the disqualified sailors. In my opinion, the substantive learning for the broader Pacific Northwest sailing community isn’t from the racers’ contention, but in trying to understand the panel’s decision.

Baldwin says there’s a critical gap in the point of view from the sailors and the perspective of the pilot on the bridge of a commercial vessel. “It was clear to us looking at the evidence and listening to the testimony, there was little available to the pilot of the vessel Volos other than what he had done.”

Captain Hail took it a step further, “Racers need to put themselves in the position of the pilot and understand their thought process, realizing a 600-foot vessel traveling 11 knots will take 1.25 miles and 8 minutes to stop at emergency back. They will also travel 1/3 of a mile in the direction of their original travel and 2 minutes to make a 90 degree turn (Volos took 3 minutes). This is why a pilot must make decisions well in advance.”

Baldwin described individual sailors who presented perspectives in the hearing (and since) that they were far enough down the course and in the outbound lane, and therefore posed no impediment to Volos’ inbound path. Baldwin appreciates this position, but indicates that what this perspective fails to understand is that “they were part of what appeared to be a wall of boats, and their presence in the outbound lane limited the opportunity for the pilot to seek permission from Vessel Traffic to move into that lane to avoid.” Ultimately this caused the pilot to take what Captain Hail described as “drastic action,” and Baldwin called “a radical move, not something that anybody had seen in those waters.”

To me, this is the most salient takeaway from this process: while individual boats may feel capable of avoiding commercial traffic safely and legally, if a group of boats as a whole appears as an impediment to commercial traffic, the entire group of boats may be held responsible. Baldwin elaborates that the decision found that these boats were “individually and collectively” impeding traffic (so it isn’t only guilt by association or merely by proximity to guilty parties). The panel found that all disqualified boats were “about to enter the lanes, in the lanes, or about to exit.” And perhaps most importantly, Baldwin says, “It will be the pilot, in every case, who decides who is impeding and who is not impeding.” Considering how far in advance a pilot must make a decision, Rimkus added that if a boat is seen as an obstruction by the pilot at the time of the decision, even if that boat is later able to keep clear, it is still an obstruction.

Additionally, Rimkus noted that none of the boats made obvious course alterations to indicate that they were keeping clear, and that the regulations require “that they make a course change that is visible by radar.” Baldwin indicated that, while it is not an official position, what he knows to be true is that it typically requires tacking or jibing to make clear to a pilot that a boat has altered course to avoid.

Some other learning has to do with race organization and management. Through this process, there’s a fresh opportunity for more open lines of communication between local OAs and VTS. This is thanks, in part, to this US Sailing panel and their expertise from other racing venues around the country, where there are clearer protocols that enable more proactive, collaborative communication between OAs and VTS. Baldwin confirmed that this doesn’t alter the sailors’ responsibilities, and might even encourage more dedication to the existing standard that sailors monitor the appropriate VHF channel(s).

Rimkus praised the constructive spirit VTS and Captain Hail brought to this process. He noted that it could have been an entirely different situation if VTS decided to take a more punitive approach. Rimkus runs a lot of racing in Cascade Locks, Oregon, where the race committee escorts all the barge traffic through the race course. He says, “If that was required of all the Seattle clubs by VTS, as it is for certain events in the Bay Area, it would cripple sailboat racing on Puget Sound. It’s hard enough to get volunteers to go out on the water to run races, let alone get two to three chase boats to escort any commercial traffic through the racing area.”

Rimkus continued, “I’m incredibly amazed at how cool [Captain Hail] has been on this whole process. Seattle is very lucky to have [him] especially because he’s a sailor. I know they’ve had problems in Boston, Charleston, Long Beach, and San Francisco — and VTS was nowhere near as compassionate as they were here. [Captain Hail] obviously doesn’t ever want this to happen again, but he wants to be proactive not reactive.”

Captain Hail concluded, “VTS doesn’t want to put a damper on the thrill of competitive racing. Been there. But we need to keep it safe for everyone….”

The panel also discussed some opportunities for local race organizers to write clearer, more sophisticated regatta documents that could provide protest committees with more nuance in interpretation — as ARO, Rimkus is ready and eager to assist organizers in these efforts. Better regatta documents can also offer sailors more clarity as to their responsibilities to sail within the rules.

Ultimately, this “unfortunate set of unpredictables” will be remembered as a good day of sailing for some, with a disappointing result for others. Hopefully, I’m not the only one who sees it as a worthwhile opportunity to better understand racing, the rules, the venues where we go racing, and the vessels with whom we share the water. Baldwin says, “I really want to credit the sailors. The general knowledge of the racers was higher than we had expected. They know what they’re doing. They understand the circumstances, and what’s required of them in these circumstances.” And thanks to this process, we all may understand these things a little more deeply.

Joe Cline

Joe Cline has been the Managing Editor of 48° North since 2014. From his career to his volunteer leadership in the marine industry, from racing sailboats large and small to his discovery of Pacific Northwest cruising —Joe is as sail-smitten as they come. Joe and his wife, Kaylin, have welcomed a couple of beautiful kiddos in the last few years, and he is enjoying fatherhood while still finding time to make a little music and even occasionally go sailing.