Roche Harbor is like something out of a fairy tale—a weird and wondrous sea story with ancient (or at least aging) mariners, historic vessels, wandering spirits, ethereal bells, and a pleasant marina, all surrounded by an enchanted forest. From the moment I docked here years ago during my first cruise to the San Juan Islands, it has been my favorite stop.

Initially, it was the comfort that appealed to me. As our sailboat approached guest moorage, two crisply dressed dock hands helped us tie up and sign in. The showers were the best I’d seen at any marina in the Pacific Northwest. Neighboring power boats towered above our smaller vessel on all sides.

“So, this is how the other half lives,” I muttered to Frank as we walked down the dock. “I could get used to it.”

Reportedly, actor Ted Danson occupied one of the nearby boats (I never saw him). A few years later, my family ducked into the protected waters of Roche Harbor, located on the northern tip of San Juan Island, after a very spirited sail on an Outbound 46 in Spieden Channel. Once again, I got a glimpse of the charming waterfront bursting with flowers, tidy gardens, and genteel manners. My relatives still talk about watching the Colors Ceremony over cocktails at sunset.

The Waterfront

One of the things I’ve come to love about Roche Harbor is how quickly the layers of history are revealed, even to a casual observer. Its story is written on the surface of the land and sea. A Coast Salish community known as Wh’lehl-kluh once thrived here, erecting longhouses and shell middens, still visible along the shore. Tribal vessels continue to stop at Roche Harbor during the annual Canoe Journey, as they paddle through their ancestral marine highways.

British officer Richard Roche scouted the area in the 1840s and 1850s, looking for a site for the Royal Marines encampment during a period when the United States and the United Kingdom had agreed to occupy the San Juans jointly. (For a description of the resulting “Pig War,” see “Sentinels of San Juan Island,” in the August 2022 issue of 48° North). The eventual location, English Camp, is located in Garrison Bay just south of Roche Harbor and is now managed by the National Park Service; it can be viewed today from the water and ashore.

During the late nineteenth century, Roche Harbor became a company town dominated by the lime industry. In 1886 attorney John S. McMillin established the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Co. on the waterfront, expanding on existing lime works and doubling production. McMillin’s company blasted quarries to mine the limestone, while constructing warehouses, offices, wharves, and loading platforms to store, sell, and transport it. His company installed several new kilns to burn the limestone into powder, a process called calcination. The resulting lime—used as mortar for masonry buildings, in the production of paper, and as a fertilizer—was in high demand in this rapidly developing region. Within a few years, McMillin’s company became the largest lime works on the West Coast.

Today, remnants of a lime kiln can be seen from the docks, and as boaters approach they can easily see the intact layout of the original village rising up the hill. When McMillin established his lime operations, Roche Harbor was a relatively remote and isolated outpost in the San Juan Islands. In the paternalist manner of a nineteenth-century industrialist, McMillin provided just about everything his employees needed, including a store, church, hotel, school, doctor’s office, and post office, as well as small, uniform cottages. Most of these structures are still there, suggesting the orderly, controlled, hierarchical life of the lime baron and laborers working and living side by side.

Employees at Roche Harbor included Scandinavians and Russians. There were also Japanese men and their “picture brides”—arranged through a matchmaker who paired women with immigrant workers using photographs and family recommendations—who lived in segregated sheds near the barrel factory. In the early years, wages were paid in the form of script that was good only on site, at the company store.

McMillin’s picturesque home stood at the center of the village, overlooking the water and the adjacent sunken gardens. The 22-room Hotel de Haro, located nearby, housed distinguished guests visiting the factory and waterfront. McMillin was a friend and advisor to many politicians and statesmen, and at one point narrowly missed being elected to the US Senate. He served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention for several years. President Theodore Roosevelt visited McMillin in Roche Harbor in 1906, sleeping in the Hotel de Haro. As a flamboyant gesture, Roosevelt called in the destroyer USS Jones, which anchored in view of Roche Harbor on its way to the Pacific. McMillin, also seeking to impress, arranged a sumptuous salmon barbecue on nearby Henry Island, including a live band and a dance on a tree-lined barge. Later, McMillin similarly entertained President William Howard Taft at Roche Harbor.

Little has changed since McMillin’s day, at least in terms of the village infrastructure and what it suggests about social interactions. “It’s not difficult to conjure the actions, antics and feelings of the people of Roche Harbor during the past century,” wrote one observer in 1972. “The ghosts are there for anyone who wants them—and maybe even for some who don’t.” (Lynette Evans and George Burley, Roche Harbor: A Saga in the San Juans, 1972).

The hotel, with its extensive veranda, railing, and turret, has an Old World vibe that inevitably inspires spooky stories. Many tales feature Adah Beeny (sometimes spelled “Ada Beane”) who may have served as a governess and personal secretary to the McMillins and died—possibly while pregnant—under mysterious circumstances. Her spirit reportedly lingers in the hotel. “Things happen in this building,” a front desk clerk informed me recently. “Doors slam and windows rattle for no reason.” According to some accounts, Ada haunts the adjacent restaurant as well. Whatever your view on the spectral residents of Roche Harbor, it is clear that John S. McMillin’s vision for the company town casts a long shadow that is visible to this day.

The Boats

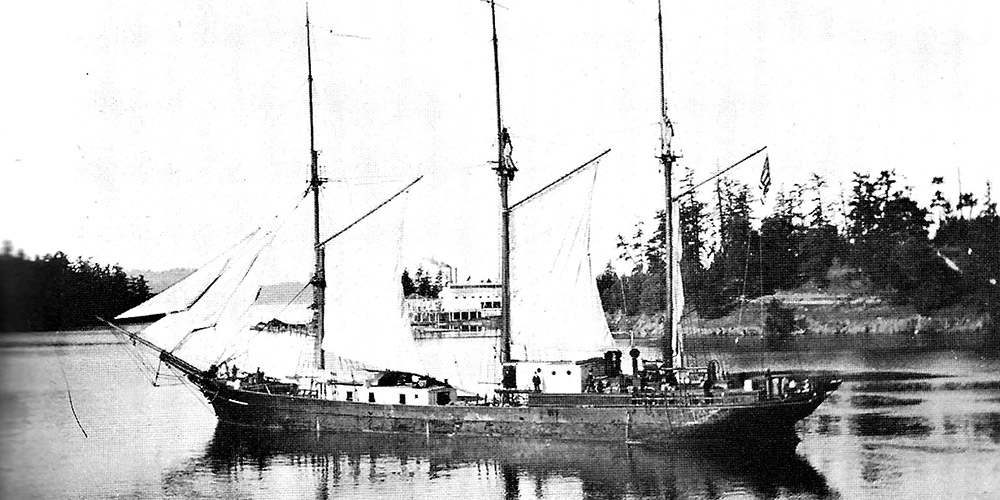

Passenger steamers, barges, and tugs crowded Roche Harbor during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Ships were essential for transporting barrels of lime, and the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Co. maintained its own fleet, including Archer, a schooner purchased in 1906. This vessel became famous for its quick runs carrying lime to San Francisco, a city rebuilding after the great earthquake and fire. Lime is a highly combustible cargo, and several vessels, including La Conner and J.B. Libby of the mosquito fleet, burned and sank while transporting it.

For McMillin, the pride of Roche Harbor was his yacht Calcite. In September 1908, the lime baron, who was commodore of the Roche Harbor Yacht Club, joined fellow magnate R.P. Butchart (who developed his quarry into Butchart Gardens), McMillin’s son Fred, and photographer J.A. McCormick on a three-week cruise to Princess Louisa Inlet aboard this boat. Built on Lopez Island, Calcite was “quite a spiffy yacht” that “provided all the comforts of home.” Measuring 50 feet 10 inches overall, Calcite offered sleeping accommodations for 10 guests, along with electric heat and lights, running water, and storage space beneath the afterdeck.

McCormick’s account tells of a dreamy journey through the Salish Sea in an era before desirable destinations were thronged with pleasure boats. Calcite’s guests and crew visited Victoria, Chemainus, Campbell River, Powell River, and Princess Louisa Inlet, exploring waterfalls and other scenic wonders while fishing and hunting along the way. This was a voyage of privilege, where the captains of industry dressed formally for meals served on linen tablecloths, prepared by Jim Nagioka, ship’s chef and steward. “He was never at a loss for something new in pastry or pudding,” McCormick wrote, “and was continually giving us the last word in delicious compounds from his three-by-five-foot galley.”

Their luxuries included a record player, used on several occasions while at anchor. “We … played the phonograph until midnight, entertaining the logging population ashore,” McCormick commented. ”With the horn turned shoreward the people were given a rare treat, as we had dozens of the finest records, including a number of the sacred hymns.” (John A. McCormick, Cruise of the Calcite, originally written in 1908). It is not clear what the loggers on shore thought of this concert.

After McMillin’s death, his son Paul sold Calcite, possibly to someone in Port Townsend. The vessel was converted to a tug and “doubled as a pleasure craft and working boat” (Richard Walker, “Iconic Boats of Roche Harbor’s Past,” Northwest Yachting, 2019). Calcite was a harbinger of the many affluent recreational boats that would later frequent Roche Harbor.

The Woods

Just outside the marina there is a road (turn left when exiting the docks; go past the church) that leads to a forested trail. Follow the signs pointing toward one of San Juan Island’s most magical and bizarre sites: the McMillin Mausoleum, called the “Afterglow Vista.” It is a short walk from the marina but you’ll find yourself in a different world. First, the trail meanders through several headstones, some of which are enclosed in white picket fencing. Roche Harbor workers, some Japanese, are buried in this cemetery, and the number of child graves suggests the hardships of life in Roche Harbor during previous eras. Eventually the path leads to a large seven-pillared monument sitting on a small hill.

Middle: The chairs circling the limestone table contain the ashes of McMillin family members.

Right: John S. McMillin’s chair.

McMillin, who died in 1936, constructed this memorial as his final resting place. His membership in the Masonic Order is reflected in the many symbols etched into the structure. The two sets of stairs approaching the monument represent the steps within the Masonic Order. Arranged in groups of three, five, and seven, the steps signify the three stages of life (youth, adult, elderly), the five orders of architecture (Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, Composite), the five senses, and the seven liberal arts and sciences (grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy). The columns are the same size as those in King Solomon’s temple. One is incomplete, reminding us that individuals die before their work is finished. Six chairs circle a limestone table in the center, serving as a crypt for the McMillin family’s ashes and signifying unity during life and death. McMillin’s plan to cap the rotunda with a dome proved too expensive, and it remains open to the elements, offering a view of the fir trees that tower around the structure.

For decades, tales of strange phenomena have surrounded this site. Mysterious blue orbs supposedly hover above the limestone table, and observers claim to hear disembodied voices, sometimes catching glimpses of shadows sitting in the chairs. Frank and I have visited the mausoleum many times, and eerily, we have never encountered anyone—living or spectral—on the trail or at the site. To me, it is a place of quiet reflection, where the natural and the mystical blend in a way unique to Roche Harbor.

The carillon bells from the church greeted me as I strolled back through the forest to the dock on my recent visit. The tune “Somewhere My Love,” seemed perfect, as I recalled the lyrics “you’ll come to me out of the long ago…” Today, Roche Harbor offers modern amenities and exceptional comforts, but here the “long ago” is never very far away.

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell: Ding-dong.

Hark! Now I hear them,—ding-dong, bell.

Ariel’s song in The Tempest, William Shakespeare

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor residing in Seattle. For more information, see the booklets Cruise of the Calcite, by John A. McCormick and Roche Harbor: A Saga in the San Juans, by Lynette Evans and George Burley.