You may have recently heard about the rescue of the University of Washington’s Seaglider, Pigeon, in the Pacific Ocean by a cruising family from British Columbia. Here’s the incredible story courtesy of UW’s Layla Airola…

Established in 2022, the Student Seaglider Center (SSC) at the University of Washington is a student-led, student-run lab dedicated to training the next generation of ocean scientists and engineers. Through hands-on experience, students plan scientific missions, rebuild and maintain Seagliders, and pilot them on extended deployments. The SSC is home to 24 undergraduates from across UW and 3 graduate students from the School of Oceanography. The team is guided by mentors Sasha Seroy, Rick Rupan, Fritz Stahr, and Charlie Eriksen. The lab is structured into three core teams: Science, led by Chief Scientist Katie Kohlman. Engineering & Technology, led by Chief Engineer Ellie Brosius. Business & Outreach, led by Chief Business Officer Layla Airola.

Seagliders are autonomous underwater vehicles capable of collecting high-resolution vertical profiles of ocean data—from the surface to 1000 meters depth. They measure oxygen, temperature, salinity, chlorophyll, and turbidity. Piloted remotely from land, Seagliders offer a low-cost, long-duration alternative to research cruises. They can stay at sea for 7 to 9 months, gliding silently beneath the waves. Thanks to Chief Engineer Brosius and her engineering team, the SSC has successfully rebuilt four gliders so far.

A Mission Like No Other

In November 2024, Chief Scientist Kohlman embarked on an ambitious mission. Aboard the R/V Sikuliaq, she joined a group of researchers from WHOI, Scripps, APL, and OSU investigating mixing beneath Tropical Instability Waves (TIWs) in the equatorial Pacific. These TIWs, large wave-like meanders along the equator, influence ocean mixing, air-sea interactions, biological productivity, and even global climate patterns. It took a week of steaming to reach the deployment site at 0.5°N, 140°W.

In November 2024, Chief Scientist Kohlman embarked on an ambitious mission. Aboard the R/V Sikuliaq, she joined a group of researchers from WHOI, Scripps, APL, and OSU investigating mixing beneath Tropical Instability Waves (TIWs) in the equatorial Pacific. These TIWs, large wave-like meanders along the equator, influence ocean mixing, air-sea interactions, biological productivity, and even global climate patterns. It took a week of steaming to reach the deployment site at 0.5°N, 140°W.

There, Kohlman deployed a beloved glider from the SSC fleet—a hot pink Seaglider built in the early 2000s, affectionately named Pigeon on November 21 around 3 a.m. The name was fitting: like homing pigeons, the glider was meant to return home—on its own. After rendezvousing with NOAA PMEL’s TPOS Saildrones and the Wirewalkers from APL and Scripps, Pigeon was programmed to fly herself nearly 1300 miles from the equator to Hawaii, collecting data all the way.

This was not a typical glider mission. Few have attempted such a long, remote traverse. But Pigeon and her on shore support team were up for the challenge.

Trouble Midway

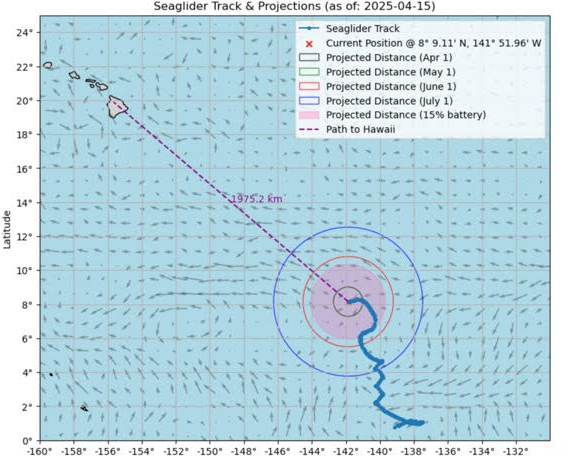

Three to four months into the mission, pilots noticed something was off. Pigeon was still transmitting data and GPS signals, but she wasn’t flying efficiently. Progress had slowed dramatically. With no onboard cameras and no ships nearby, the cause was a mystery. What was clear: at this rate, she wouldn’t reach Hawaii before her batteries ran out.

The SSC launched an urgent search for vessels in the region that might assist with recovery. But the central Pacific is vast and lonely. Ships were few and far between. Pigeon’s plight underscored both how remote her journey was and how valuable her data had become.

The SSC launched an urgent search for vessels in the region that might assist with recovery. But the central Pacific is vast and lonely. Ships were few and far between. Pigeon’s plight underscored both how remote her journey was and how valuable her data had become.

By May 26, 2025, Pigeon’s dive battery finally died. She could no longer submerge and was now drifting at the surface. Fortunately, she was still pinging her location. Ironically, ocean currents began pushing her toward Hawaii faster than she had ever traveled while diving. Hope flickered.

A Family, A Sailboat, A Rescue

Thanks to relentless outreach spearheaded by Chief Business Officer Airola—including a feature in Sail Magazine, Yachting World, Latitude 38, and Blue Water Sailing—we received an email from a Canadian family on May 30. The Ventilly Family, aboard their 36-foot sailboat Oatmeal Savage, were sailing from Tahiti to Hawaii when they came across our call for help and offered to attempt a rescue.

As they approached Pigeon’s last known location, the family received a distress call from friends aboard SV Flow, about 200 miles behind. Flow had lost their rudder and needed to abandon ship. The Ventillys turned back and rescued them—adding two adults and their belongings to their already small sailboat.

Still, with six people aboard, they continued toward Pigeon.

Reunion at Sea

On June 5, in the deep blue Pacific around 10°N, 145°W, the Ventillys spotted our beloved hot pink Pigeon. They hauled her aboard and secured her to the swim platform. The issue was immediately apparent—half of her rudder was missing. Without it, she had been struggling to steer and maintain buoyancy for months. How it broke off remains a mystery—one of the ocean’s many secrets.

Coming Home

On June 11, Oatmeal Savage pulled into Hilo, Hawaii, where Chief Scientist Kohlman and SSC member Paige McKay were waiting dockside. After six months and over a thousand miles, Pigeon was on land.

Her journey was historic. From the equator to 10°N, she collected continuous profiles down to 1000 meters, capturing: Tropical Instability Waves, a transect of the equatorial current system, the biologically rich cold tongue, the Intertropical Convergence Zone, and much more.

Already, two undergraduate students (Kathryn Farabaugh and Lydia Kelley) have analyzed and presented some of Pigeon’s collected data at the UW Undergraduate Research Symposium in May 2025).

What Comes Next

Now back in Seattle, Pigeon will be cleaned, repaired, and prepped for her next mission. Meanwhile, SSC members are beginning to analyze the treasure trove of data she collected during her record-setting voyage.

What started as a student-led experiment turned into a testament of grit, teamwork, ocean science, and a little bit of maritime luck.

Pigeon flew.

And she came home.

If sailors/boaters are interested in helping researchers in the future, Yachts for Science is a great organization that posts calls for assistance on their social media.

Editor

48° North Editors are committed to telling the best stories from the world of Pacific Northwest boating. We live and breathe this stuff, and share your passion for the boat life. Feel free to keep in touch with tips, stories, photos, and feedback at news@48north.com.