Lessons Learned Cruising: Jamie Gifford shares his experience helping east coast cruisers with weather routing

On this day, I have two boats galloping north at 10 knots. The sailing is nice, boosted by 3 knots of Gulf Stream current along Florida’s east coast. This has elements of a unicorn passage. After dark, it’ll be all dragons. I’m anxious for both families. I didn’t exactly send them out into this night. But I didn’t stop them either.

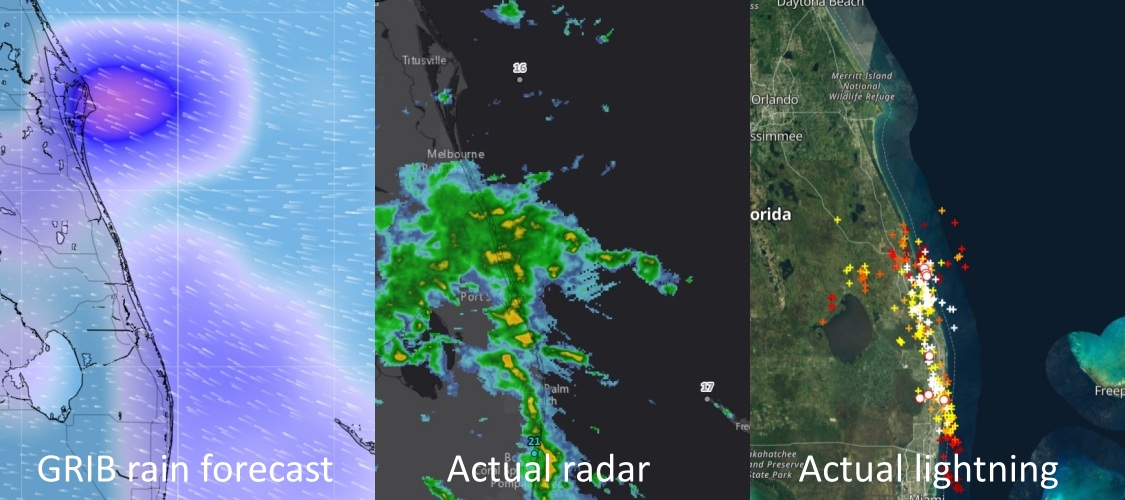

Realtime weather radar shows heavier rain approaching. Florida now has tornado and flood warnings. Damn. Lightning hotspots continue to increase along the coastline. The dragons are coming. 1,700 miles west, Totem bobs in softening afternoon wind waves in the Sea of Cortez. We haven’t had a drop of rain in 6 months. No dragons either. We’ll have a gorgeous full moon rising over Isla Carmen in a few hours. Nothing like my Gulf Stream boats speeding through darkness and dragon fire. I am the chess master, sliding pieces past danger. I am the fool, thinking I control the board.

I’ve only recently come to accept that I provide a weather routing service. I’m not a meteorologist, not even a pretend one. I’m never the assertive voice when a group of sailors debate a weather window for the next passage. Information sharing is helpful. Selling an interpretation only masks a hidden agenda. I thought I understood weather forecasting pretty well when I was a racing sailor. Weather had tactical value and I was competitive. Then came the first big and very unexpected squall while delivering a J/35 to Newport, RI. Didn’t see that coming, but could have if I’d known where to look.

Family cruising in Puget Sound and beyond shifted desired weather traits from tactical to comfortable. The unicorn passage: fully at ease with surroundings in the magic and enchantment of glorious sailing. Unicorns are rare, elusive. Waiting is tedious; not getting you to that next beautiful anchorage you’ve dreamt of, frustrating. Instead, interpret the forecast and go. Rarely expecting unicorns, always hoping not to see dragons. Sometimes getting it right. Sometimes not, always comparing and contrasting forecast and reality after the anchor dropped. After hundreds of passages and assessments, my technical weather knowledge is hopelessly mediocre. My particular weather superpower is translating meteorological data into “this is what it’s going to be like.”

My Gulf Stream boats aren’t off to the next dreamy anchorage, they’re retreating to neutral territory. Like many, they’d been COVID-19 restricted in the Caribbean. Uncertainty of a global pandemic and hurricane season looming like a nightmare monster set them on a path to Maine. It’s a return to home for one family. A gorgeous new cruising region for the other. A big step closer to predictability for both. The path is about 2,500-miles long. Beginning in turquoise water of the US Virgin Islands, where warming temperatures bring increasingly volatile weather. Going north in May and June quickly bumps into colder weather and frequent gales springing from the east coast out into the cold Atlantic.

A few weeks before picking a good enough window to depart paradise, we began the conversation of which route to take home. We sailed Totem from the Caribbean to New England in 2016, on a direct route via Bermuda. This shaved 1,000 miles from a path along the US coast. Bermuda was closed and the likelihood of gales was high, so, that option was a no go. A less offshore route meant skirting the Bahamas, but they were also closed — even for vessels in transit. This longer path without bailout options suddenly got riskier. Fortunately, Salty Dawg Rally organizers stepped in to help. They worked with Bahamian officials to create an innocent passage status list of boats for cruisers repatriating the US and Canada. Once on this list, crews could stop in Bahamas to wait out weather, or procure food and fuel.

With a bailout in the Bahamas possible, most of the dozen boats that sought out professional weather guidance from this amateur router preferred to skirt east of Bahamas and make landfall in Chesapeake Bay. This unlikely outcome wasn’t realized by any of them. Through the weather window, I could point out dragons lurking. Boats began peeling off to take innocent passage through the Bahamas. Better to make some progress than wait and wait for the unicorn passage. These boats leap frogged through the Bahamas, unable to step ashore but grateful for the respite. Each made landfall in Florida.

My last two boats, patient or stubborn I won’t say. As their weather router, it’s not my role to tell them when or where to go. It has to be their choice. It can be frustrating, when they don’t follow what I think they should do. Then I remember the times I choose poorly. This includes last night on Totem. I thought the afternoon swell would fade for a flat night and easy sleeping. Instead it was a restless, rolly night at anchor. There is no crystal ball. I don’t push my interpretation, only describe what I see.

A huge low off of New England, with a trough extending to the Bahamas and I picture myself with the young families. One with some offshore experience. The other hadn’t sailed overnight before. I picture the headlines — virgin family departs Virgin Islands for innocent passage to Bahamas. What could go wrong? Both boats added experienced crew. With a gift of easier weather, they managed nicely. And when the weather got more complicated as they went, they arrived in Florida without drama.

On this night, northbound along the Florida coast, finesse is the key. I described volatile conditions before they set off. No bad wind or waves, but potential squalls to 40 knots, and lightning. Those dragons are real and can be terrifying. A quick start guide to successful family cruising would do well starting with this rule #1: Avoid Terrifying.

My guidance was for a slow start to let the band of unsettled weather pass ahead. I watched the satisfying progress on their satellite tracker positions. They were only 50 miles offshore, within real-time weather radar range. With another online resource I could track real-time lightning strikes (https://map.blitzortung.org/). On another browser tab I rechecked the GRIB Rain forecast for the 20th time. Lifeless grey blobs, with smaller pink ones denoting rain intensity. Lifeless, almost meaningless until you see the dull blobs as the smoke and flames from dragon fire. That gets the heart rate up.

The tools I used aren’t meant for piloting, but that’s how I used them. To navigate around hazards. Crudely plotting the lightning’s advance (radar and lightning screens didn’t show Lat/Lon lines) I went against my own rule not to tell them what to do. “Speed now please, all you can make. And change course ten degrees to starboard,” I typed into the message box. The screen confirmed the message sent. Several minutes passed before the reply arrived, “Headsail out, sails trimmed, and course changed. Making out lightning in the distance.”

Virtual chess and mythical creatures. I could feel their tension as lightning approached. I could almost hear the voice crack, as if there was a voice in the next message, “lighting is getting intense, will we miss it?” With a few more course adjustments, volatile weather passed just south of the two boats. Actual conditions reflected forecast conditions pretty well, except for being 40 miles closer to my boats then the lifeless grey blobs showed. I learned along time ago that the weather isn’t supposed to do what the forecast says. The dragons that were supposed to strike fear deeper into the night, was now gorgeous lightning safely astern. Another experience. Another assessment. Another way to express lifeless grey blobs.

Behan and Jamie Gifford

Behan and Jamie Gifford set sail from Bainbridge Island in 2008 and are currently aboard Totem in Mexico. Their column for 48° North has traced Lessons Learned Cruising during a circumnavigation with their three children aboard and continued adventures afloat. Follow them at www.sailingtotem.com