The dispute with my 14-year-old son started, as many disputes do, with a promise. I had agreed to let him captain our 37-foot Beneteau through the Malibu Rapids at the mouth of Princess Louisa Inlet. I wanted to give him the opportunity to take responsibility, grow as a person, and build his confidence. Instead, the opposite happened.

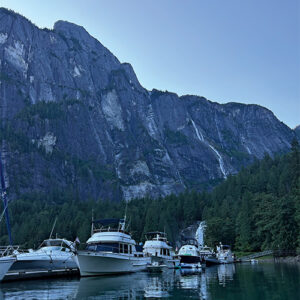

Malibu Rapids are notoriously challenging. It’s a narrow opening at the entrance to Princess Louisa Inlet, a hidden 4-mile fjord at the top of the Jervis Inlet north of Vancouver. From the outside, the fjord doesn’t reveal its real splendor. The entrance is a cut in the rock—maybe 200 feet wide—and it zig zags so that you can’t really see what’s around the bend.

Part of what drew us there was the legend of the place. My wife, Tara, was reading Muriel Wylie Blanchet’s book “The Curve of Time” which describes Blanchet’s summers in the 1920s spent exploring British Columbia on a 25-foot boat with her five young children. For her, Princess Louisa was a magical place with “brighter stars than you see anywhere else.” From other cruisers, we had heard it described as an unspoilt Yosemite, accessible only by boat or float plane.

But we also heard it was dangerous. As the tide rises and falls, a massive amount of water churns through the entrance like a stampede of cattle, turning the narrow gap into galloping rows of waves. We heard a story of an impatient captain who decided to run it before slack tide. He got halfway into the cut and couldn’t make forward progress as the water rushed out. When he turned his boat to go back, the current grabbed hold and capsized him. In 2016, a teenager fell into the rapids and drowned. The place has earned its reputation.

We set off at dawn on July 11, 2024 from Pender Harbor. Low tide at Point Atkinson was at 12:42 p.m. Another sailor at Pender told us to add 35 minutes to get low tide slack at Malibu Rapids so we needed to hit the entrance at about 1:15 p.m. It was about a 40-mile journey and the wind models showed some strong headwinds later in the day. We had to hustle.

But my teenager wouldn’t get out of bed. “I thought you were going to captain,” I said.

“You asked if I wanted to captain the rapids, not the whole thing,” he groaned and put a pillow over his head.

Maybe that was my first mistake. I could have insisted he lead the whole day but I decided to let him sleep. I figured he’d be better off if he was well-rested for the rapids. And I wanted him to want the responsibility. I didn’t want to force it on him. He had been excited to tackle the rapids and I thought that was a good place to start. Sure, captaining is about much more than navigating a short stretch of exciting water; but I thought to myself, “Let’s just start with this bit that he’s enthusiastic about and build from there.”

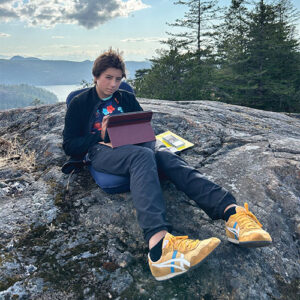

I also wanted to be sensitive to the fact that it was a unique time for us as a family. Our older son, Kal, had just left home to study at the Northwest School of Wooden Boat Building in Port Hadlock, Washington. For 18 years, our family unit was four people. Now, with Kal off on his own, we were just three. Kirin had just graduated from 8th grade and was about to begin high school. My wife and I saw all these transitions as an opportunity to shake things up, so we rented out our house in San Francisco and set out to sail for six months. Kirin would spend the first semester of freshman year on the boat, doing “boat-schooling.” We got Starlink so he could take online classes, my work in media was already on Zoom, and my wife took a sabbatical.

For me, it had always been a dream to sail for an extended period. During the pandemic, we cruised as a family in the Caribbean and that sparked a burst of creativity. My older son and I started writing a novel together during that time and were able to sell it to a publisher. It tells the story of a family who walks away from the modern world to live on a boat in the Caribbean (it’s called “The Uncertainty Principle” and it comes out this month).

The book was on my mind as we motored in light wind up Jervis Inlet that morning. The fictional mom and dad we wrote about were well-meaning but didn’t always make the right parenting decisions. Some of that stemmed from my own doubts. Why was Kirin so grumpy all the time? Was I doing something wrong? Maybe the whole idea of sailing for six months was a doomed experiment. After all, what appeals to an adult about sailing—the quiet, the lack of devices—often sounds terrible to a teenager. Kirin seemed to be living the experience of the main character in our book: he was sick of hanging out with his parents all the time.

That’s why I thought it would be a nice gesture to give him command of the boat. Let him be in charge and show that I didn’t need to always boss him around, particularly as he got older and more mature. But these were all thoughts that I had by myself, standing at the helm, while Kirin continued to sleep down below.

inside Princess Louisa Inlet.

For hours, we were the only boat we could see. Jervis is a dead-end and has no towns as you go north so it wasn’t surprising that we were alone. It was a blue sky day and there was almost no wind at that early hour. The mountaintops on either side had snow. It was beautiful but also forbidding. I felt so much solitude out there.

Soon, the wind picked up, whistling through the rig at 15 knots from up the inlet. It was a headwind, but the inlet curved like a squiggly line, so I hauled up the sails and could make some good progress tacking. I shut down the engine and was still on target to arrive before slack tide.

The sudden quiet must have woken Kirin because he poked his head up the companionway.

“Where are we?” he asked, bleary eyed.

He climbed out and stood beside me at the chartplotter. On the screen, a boat popped up on AIS. It was far behind, many curves back, so we couldn’t see it. Kirin tapped the icon and saw that it was moving at 7 knots. We were only getting 5 knots at best. In a moment, an entire armada of boats appeared even farther behind, probably a dozen in a tight pack, all racing forward at more than 10 knots.

“What is going on?” Kirin asked.

“I guess we’re not alone anymore.”

It soon became clear that there was a race. A contingent of motorboats was sprinting up the inlet to get to Princess Louisa. We knew that there was only one dock inside the fjord, a handful of buoys and not many good places to drop the hook. If you didn’t get there first, you’d be forced to anchor on a steeply plunging granite shelf. Not ideal.

Kirin and I watched warily as the pack of boats closed in on us. There was still that one boat ahead of them all. When it rounded the bend, I was surprised to see it was a sailboat with its mainsail furled but its jib up. It was still going 7 knots according to AIS.

“Cheaters,” I said. They were motor-sailing. I gave a big speech about the purity of sailing, how the early explorers didn’t have engines, how nice it was to listen to the sound of the wind, how we got up so early so we could enjoy the experience, and then I turned on the engine.

I started out at 1500 RPM—just a little assist that got me to 6 knots. But then I noticed on AIS that the other boat had notched up to 8 knots. Bastards. They were close to the wind while I was still tacking. I bumped the throttle up a little bit more.

Within a couple hours, they were off to starboard and we were looking at each other with our binoculars. He had edged up to 9 knots in a sailboat about our size. Behind us, a dozen Ranger Tugs were surging forward a couple miles back. They were gaining on us but we were still ahead. The entrance to Princess Louisa wasn’t that far now. We could rev up more but we were ahead of slack tide.

“Let’s go faster,” Kirin said, alert to the competition.

“We could get there first maybe but then we’d have to wait for slack, so what’s the point?”

“But they’re going to win.”

“Win what?”

I can’t say I didn’t feel the pull to race the other boat to an imaginary finish line but I also recognized its futility.

“So you’re just going to let them pass us after we’ve been ahead this whole time?”

“Yes,” I said, trying to look wise.

“That’s dumb.”

“I offered you the helm this morning,” I countered. “You ready to take over?”

“After I eat,” he said, disappearing below.

The sailboat won the “race” and got to the entrance first. We weren’t far behind and within 30 minutes, there was a veritable traffic jam of boats trying to hold position while the current pushed us down the inlet. I counted 13 boats, including one small trimaran that was tacking up the inlet in the distance. They had maintained their purity but they were also the last in line.

“Well captain, you ready for this?” I asked Kirin as he came back on deck. “The helm is yours.”

He nodded, looking excited, and took the wheel. We were 45 minutes ahead of slack and the chatter on channel 16 started up. One of the Ranger Tugs announced that the two sailboats—us and the other one—had gotten here first so we had first dibs. After us, the tugs would go one by one in the order they arrived.

Kirin eyed the entrance to the fjord. There was no sign of whitewater or even fast moving current. It looked calm and safe.

“I’m going to head towards it,” he said. “If it’s too sketchy, we can turn around. But if it’s good, we can get ahead of everybody.”

I laid out all the information we had. You couldn’t see the full channel since it bent around the rock. Maybe the rapids were there. And if you got in there and got in trouble, there was limited room to navigate. It would be hard or perhaps impossible to turn around. The risk was high and for what benefit? So we could get marginally ahead? As it was, we were in second position which was pretty good.

“But it looks totally fine,” he insisted.

“The common wisdom is to wait for dead slack.”

“Okay but who’s the captain right now?” he said, suddenly holding my gaze. “Because I thought I was.”

Damn. My plan had been to boost his self-confidence and show him that I trusted him. But now he was about to make a rash decision. I had miscalculated. I assumed he would make the obvious right choice instead of gunning it through one of the most dangerous and feared navigational hazards in the Pacific Northwest.

“I’m taking back over,” I announced.

“You’re terrible,” he growled and went below, slamming his cabin door.

My wife watched the whole episode silently. Later, she told me that I shouldn’t have given him such a big bite of the apple. “Start with smaller challenges first,” she counseled.

“But sometimes you need a big challenge to inspire someone to lead,” I responded.

“And then look what happens,” she pointed out.

A few minutes before slack, the rival sailboat kicked into gear and headed for the rapids. “Frankly, this worked out well,” I said to no one, as I was by myself in the cockpit now. My wife was sitting at the bow, trying to get a better view of the channel, and Kirin was still below. “Since that other boat got ahead, I can watch what happens to them before we go in.” I patted myself on the back, but I felt pretty crappy.

I shouted at Kirin and he reluctantly reappeared. “Why don’t you do the radio call,” I offered as an olive branch. He didn’t seem that excited but did the call on Channel 16: “Sécurité, Sécurité, Sécurité, this is sailing vessel Allora approaching Malibu Rapids, inbound for Princess Louisa Inlet. All concerned traffic please advise on Channel 16. Over.”

I clicked into gear and followed the other sailboat as I saw the top of their mast disappear behind the rocks. Everything seemed fine. We traced a course down the middle of the channel and, though it was slack, there were still eddies and a confused current. I made the hard turn to starboard and saw a big pile of floating logs caught in an eddy dead ahead. Luckily, the narrow channel bore off to port and I followed the curve into the open water of Princess Louisa.

And what a sight it was. The fjord opened on both sides and rose up steeply thousands of feet to stunning snow capped mountains. Almost immediately, a swarm of Ranger Tugs blasted past us at full speed, gunning for the dock and smattering of available mooring buoys.

But ah ha! There was a buoy at MacDonald Island that was free and since the island was close to the entrance, we still had a head start. We turned in to grab it only to discover that it had a sign saying it was out-of-service, not to be used.

I looked back and saw the line of tugs zooming up the inlet. By the time we got to the end of the valley, there was no dock space or buoys.

“See?” Kirin said. “Shoulda let me captain.”

I motored near a dent in the steep southern canyon wall and watched the depth sounder go from 400 feet to 50 feet suddenly and then 30 feet. There was a 15 foot tidal swing so I circled around, backed in, and dropped in 30 feet with limited scope because our stern was close to the rock wall. I was able to scramble onto a ledge and stern tie to a thick, old tree. I didn’t sleep well that night but the anchor held through the rise and fall of the tide.

In the morning, when we gathered for breakfast in the cockpit, our argument about responsibility and maturity and rash decisions faded in the light bouncing off the granite cliffs. A waterfall plummeted a thousand feet along the north wall. There was no wind so the mountains surrounding us reflected in the water, doubling the view. It made us all feel both insignificant and glorious at the same time.

“I’m still mad at you,” Kirin said. “But this is pretty great.”

Joshua Davis (instagram.com/joshandkal) is the New York Times bestselling author of “Spare Parts, The Underdog” and the novel “The Uncertainty Principle,” out this month from Penguin Random House.