In our latest Throwback Thursday, PNW journalist David Schmidt has a conversation with adventurer and writer, Cameron Dueck. The article ran in the July 2012 issue of 48° North, a few years after Dueck departed Victoria, BC, and successfully transited the Northwest Passage.

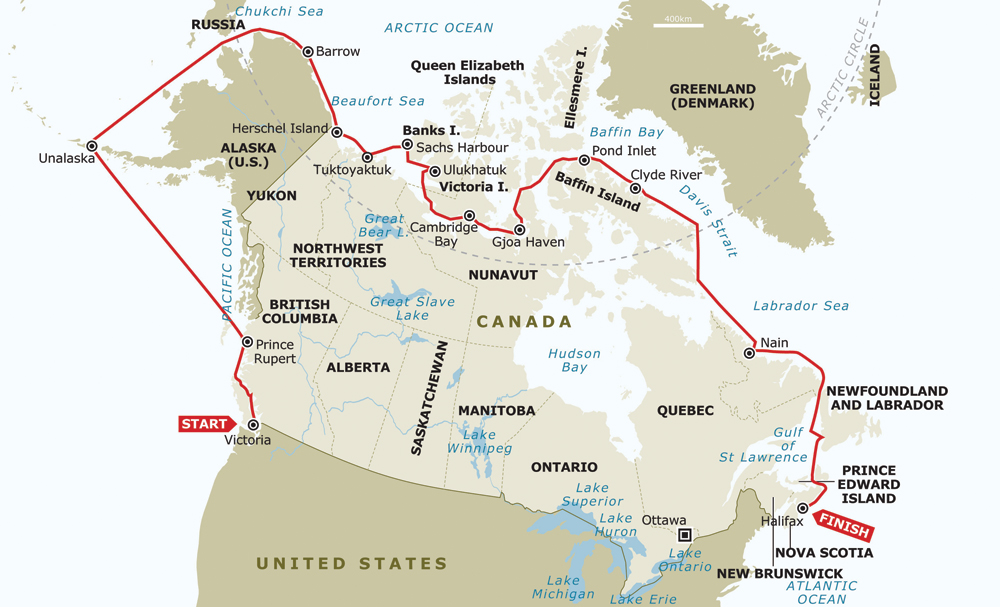

There’s an old adage that a leisure class exists on both ends of the economic spectrum. That same truism holds for sailors — some wait until the dream yacht can be procured, while others just go for it. Canadian adventurer, journalist/writer, and sailor Cameron Dueck went for it. In 2009, he and three crewmembers sailed Silent Sound, a 40-foot, 1979 Fred Amor designed, cutter-rigged, fiberglass sloop, from Victoria, British Columbia to Halifax, Nova Scotia, making what Dueck believes to be either the ninth or tenth cruise by sailboat through Bellot Strait, and about 38-40th through Canada’s fabled Northwest Passage — a route long eyed as a shortcut for shipping and global commerce — one that’s silently guarded by ice, wilderness, and a fragile-yet-unforgiving environment.

But rather than having a large trust fund, plentiful private donations or a plush corporate sponsor — as is often the case with high-profile adventures — Dueck, a magazine and newspaper journalist, self-funded some 70-percent of the trip out of his personal savings. Given his profession, Dueck involved a book-writing project into the trip from the journey’s conception. While Dueck had sailed for years, this ambitious trip was his first significant voyage as skipper, and it was also his first foray into high-latitude sailing, a combination that made for some spicy moments, no-doubt, but one that also added its own homespun richness to the adventure.

At the time of this conversation, Dueck was on a tour with his book about this project, The New Northwest Passage; and he is planning to release a film that he made about his long, icy journey (editor’s note: the film of same name as the book was released a year after this interview and won Best Feature Documentary at the 2013 Winnipeg Real to Reel Film Festival). Interestingly, his next adventure also involves a book and film project, a motorcycle and a long, solo ride from Canada to Patagonia. I caught up with Dueck to find out more about his sailing adventures in the Great White North, and to learn more about his unique style of tackling rugged adventures on a budget that’s often shy of coin but flush with ambition.

David Schmidt: How did you get into sailing?

Cameron Dueck: I grew up in the Canadian Prairies, so didn’t start sailing until I was 21 and had moved to Chicago. I didn’t know anyone in Chicago when I moved there. I was living near the lake and noticed a lot of pretty girls in bikinis teaching sailing. It struck me as a sensible way to meet people in a new city — but after my first sail, I forgot totally about the girls and was starstruck by sailing.

How did you get the idea to sail the Northwest Passage?

I quit my journalism job to sail in 2004, but after a year of deliveries; transatlantic, etc., I really missed writing. I returned to journalism to earn some money and figure things out. So, as a journalist I began looking for a book-worthy story idea, and as a sailor I was looking for a challenging voyage/project that I could lead. The Northwest Passage quickly caught my imagination, and a few years later, I started making serious plans. I had no idea what I was undertaking, but that’s often the best way to tackle these kinds of dreams. Ignorance is bliss and bravery, I suppose.

How much planning was required to pull this off?

I announced my dream to my family in 2007, and after that it quickly became a plan. So I spent a few years reading, dreaming, building up the courage, and about two years actually preparing. I was living in Hong Kong and I’m not a man of any significant

financial means, so it was an added challenge to shop online for a boat in Canada that was in my price range, and then to get it readywhile still working as a journalist in Hong Kong. At first is was just me working on the project, but slowly my friends and family got involved, and without them it would never have happened.

But in the end it was “my” dream, so I had to keep the project moving forward, despite the discouragement of having many sponsors turn me away, struggling to learn all I needed to know about my new (old) boat, and not getting a book deal until after I had the book done. Also, my entire crew dropped out two months before departure due to various reasons, so I went online and started crew dating. It was a very stressful time, but we left on time, with everyone on board.

How did your crew work out? Any mutinies or revolts?

I had one crew drop out after the first month, before we even reached the Arctic Circle. And there were other clashes amongst the crew, as you’d expect. We were on a very tight budget, I was a novice skipper and we were in tough waters, so I suppose it wasn’t a surprise. However, my crew did their jobs very well, and they literally saved the expedition from failure. I can’t thank them enough for their performance.

Did you make any modifications or refits to Silent Sound prior to the expedition?

I added a layer of Kevlar to the bow and all the way back to the beam. That was the only Arctic-specific modification, but I also upgraded many parts of the boat, [for example, adding] new radios, chartplotters and new sails. Other than that, I sailed her pretty much as I bought her.

Did you have much high-latitude sailing experience prior to the trip?

None. The coldest sailing I’d done was getting my skipper’s ticket in the Solent in July, which is pretty miserable given English weather. But I’d never seen ice from the deck of a boat before. Most of my sailing was on the East Coast of the U.S., the Med, Atlantic, and Asian waters. I’d also never skippered a boat for more than a week, and I’d never owned a boat before. Two of my crew had never sailed in their life. Yeah, crazy, I know.

What about the actual sailing? Were conditions good, or were you running the iron genny a lot?

It was spotty. We had some good sailing across the Gulf of Alaska, but above the Arctic Circle we probably motored 50% of the time. We did sail pretty much the whole way from Pond Inlet to Halifax, about 2,500 miles. We had strong winds from the autumn storms that rake across the Labrador Sea and north Atlantic.

What can you tell us about making your way through the ice?

Be patient, very, very patient. You must wait for the ice to “allow” you to pass. Also, assume nothing. Ice charts are a nice guide but they’re often wrong. Ice forecasters probably have lower batting averages than weather forecasters. We always dropped sails and motored, and we often put a man up the mast to find a way through.

Often, we’d follow a water lead that would result in a dead end, have to turn the boat around in tight quarters and try again. We left a lot of antifouling paint behind as we nudged our way through the ice.

Did you have any close calls?

I’d say anytime you’re within a few meters of ice — and there’s ice as far as the eye can see — you’re in a close-call situation. It’s how you react and handle it that determines what happens with the potential threat.

We certainly got caught in ice, but we were never immobile. We always had room to back up, [or to] try a different lead of water. The first time we saw ice was off Point Barrow, Alaska, and very quickly we were surrounded, backing up, bumping into ice floes.

Did you guys see any evidence of climate change?

It was my first time in the Arctic, so I had little reference. So, all I report is based on what the Inuit and scientists told us, and [what they] pointed-out to us. Melting permafrost is causing shorelines to collapse and wash away. We saw red foxes encroaching on areas that used to be Arctic fox territory because they’re moving north with the warmer temperatures. The tundra is sprouting grass like never before. Many hunters told us about how dangerous the ice has become. They need to travel on the ice in winter to get from village to village and for hunting, and they told me it was becoming harder to predict the ice conditions, and, in general, the ice was far less stable than it once was.

Were polar bears an issue?

We didn’t see a single bear. There are plenty around, but we just kept missing them. I believe the issue for polar bears is more localized, such as in Churchill or off the Greenland coast. The Inuit didn’t seem too alarmed about the polar bear issue in the areas we sailed through.

What can you tell us about the communities that you visited along the way?

Small, isolated, and struggling. The Inuit have been the victims of some pretty appalling injustices, and just about every polar government has messed up their bit of turf in this respect. All of the communities struggle with higher-than-average social-and-economic problems such as unemployment, the high-school dropout [rate], drug/alcohol/domestic abuse, and suicide. The towns where the people promote hunting and cultural pride are the healthiest because these activities help rebuild their confidence and sense of identity. The Inuit are resilient, intelligent, and passionate people, and getting to know a few of them gave me hope for their future.

How did your historical research of previous expeditions compare with what you actually encountered?

We did encounter serious ice in some of the same places that Franklin did, such as off Point Barrow. However, given we sailed the passage in one season in a fiberglass boat gives you all the historical context you need given the trouble expeditions a century ago had. We were also only the ninth or tenth sailing yacht ever to manage a transit of Bellot Strait, which wasn’t just a coincidence.

Did you sail away feeling better or worse about man’s place on our planet?

Well, I sailed away feeling very warm about the kindness of man — the Inuit and others in the Arctic were very, very good to us. However, seeing and hearing how their lives are being physically impacted by climate change made me feel even worse about driving SUVs and other gas guzzlers for vanity, going to Walmart to buy disposable crap we don’t need, and the general sense of entitlement we feel towards the earth’s resources. Greed comes at a very great cost.

How did the Northwest Passage compare to sailing off the coast of Yemen or crossing the Atlantic?

The sailing itself, from a physical, weather, and deck-work perspective, wasn’t that hard. I’ve been in bigger storms. But it was a huge navigational, logistical, and financial challenge for me. Poor charting, fog, spotty GPS coverage, continuous coastal sailing, and the lack of support makes the Northwest Passage a unique challenge.

Ten years from now, do you think that we will regularly see adventure cruisers sailing/transiting the NW passage?

Well, what’s regular? I think in 10 years you’ll regularly see 15 to 20 boats a year go through, if not more. But it will never be a choice between [cruising] the Med or the Northwest Passage. [The Northwest Passage] will always be seen as a bigger challenge than most cruising grounds.

Do you consider yourself to be more of an adventurer or more of a sailor/yachtsman?

Tough question. I’m not sure where to draw that line. I’ll always love the sea more than land. But in late June, I’m setting off on amotorcycle to ride solo from Canada to Patagonia to research my second book and film, this one about Mennonite culture in Latin America. I’ve also driven a cheap Chinese motorcycle across China, routing south of the Taklamakan desert on our way to Kashgar. So, I like adventure in all forms. But I do hope to return to sea for a long voyage after that, I’m just not sure where yet.

Dueck’s book, The New Northwest Passage, is published by Great Plain Publications www.greatplains.mb.ca

David Schmidt

David Schmidt is a writer, editor, journalist, and sailor. He serves as the U.S. Editor of www.sail-world.com, sailing correspondent for the international edition of The New York Times, electronics editor at Yachting magazine, and as a contributing editor at Cruising World and Sailing World magazines. David lives in Bellingham, Washington.