Kelp loss South Puget Sound is real and, despite the odds stacked up against it, boaters and scientists aren’t giving up hope.

If you hiked to see those towering giants, the coast redwoods-and all you found were a few ferns and scraggly vine maple trees, you’d be disappointed. As an occasional snorkeler and frequent small boat guy, I feel the same way about the decline of kelp forests in Puget Sound. I miss them.

On a recent multi-day sailing trip from Olympia to Seattle, I arrived near Day Island at the entrance to the Tacoma Narrows. The current was running in my favor at about 4 knots, but I was reluctant to enter this storied passage with all that water on the move. I didn’t want to deal with the hassle of deploying an anchor to wait out the tide, so I glided into a nearby kelp bed. Despite the dull thumping on my hull as the kelp was jostled by the current, I scarcely moved. Once nestled among the watery plants, I felt a sense of calm I wouldn’t have experienced in open water. When the current slowed, I rowed out into the narrows, making a safe, controlled transit.

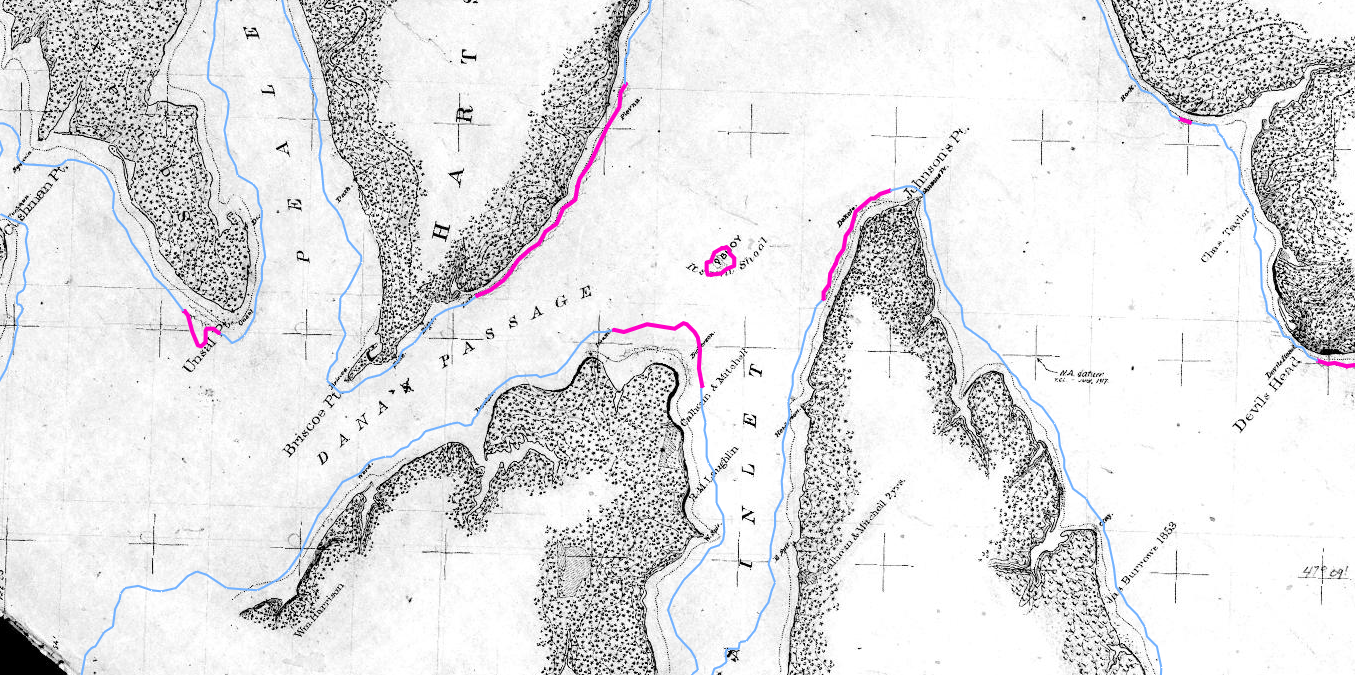

A study about long-term changes in kelp forests in south Puget Sound was published in the scientific journal PLOS One in February 2021. Using historical accounts, including nautical charts, Helen D. Berry and her colleagues at the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) surveyed the area from the Tacoma Narrows south towards Olympia. The news isn’t good: since 1878, we’ve lost more than 60 percent of our kelp forests in this area, with the greatest losses occurring since the 1980’s. By contrast, the kelp along the Strait of Juan de Fuca has mostly remained stable. For the lay person, the researchers put together a highly digestible summary in a image-rich storymap.

Maybe you sail a big boat and aren’t yet an algae fan. (All kelp are algae, but not all algae are kelp.) I get it; that jumble of “weeds” on the surface, (in reality, the very tops of the kelp forest) might look like a liability. And those long bronzy stems, and the floating bulbs that hold the kelp’s fronds near the surface to capture sunlight — you’d be forgiven for looking on them as just stuff that can foul your prop, get stuck in your intake, or simply stack up against your keel.

But if that’s all you see when you encounter kelp, you’re missing out. Take a little time to moor your big boat and hop aboard a tender, kayak, or SUP and join me. From the Squaxin Island to Spieden Channel, I’ve spent many an hour lingering and marveling at the tops and edges of these mighty underwater forests.

Once, while paused on the edge of one, I was watching a tangle of kelp gently swaying in the current, when one piece of it started to move independently. As my eyes fixed on this anomaly, out crept a two-inch kelp crab, its shell was the same golden color as its habitat. Had I not stopped, and had it not moved, it would have been perfectly camouflaged.

The most prominent of the kelps in our region is bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana). According to the DNR, bull kelp is “is known as an ecosystem engineer because it creates habitat for a wide range of species.” Growing on rocky bottoms, their stem-like stipes reach as high as 100 feet to the surface, where a natural float holds long blades that can grow to ten feet in length. A vast community of creatures, ranging from vermillion rockfish, to sleek harbor seals, to elegant turban snails, live and thrive in these forests.

For the small boater, kelp has one additional benefit. When chop and swell to seaward cause rough conditions, water between the land and a kelp bed can be a mellower, even tranquil, place to row. The kelp dampens swell and chop, as if it is in league with small craft users.

Waiting out another tide, I observed a strange type of translucent sea slug called a hooded nudibrach. Three were lined up along a kelp blade beneath the surface, their muscular feet firmly attached to the blade, the upper part of their bodies, shaped like satellite dishes, extending into the water to catch a meal of plankton. Although just a few inches long, their other-worldly appearance transported me to another planet.

Stress, to use a blanket term, is the likely cause of declines in bull kelp in south Puget Sound and elsewhere. This stress includes increasing water temperatures from climate change and worsening water quality, along with less obvious factors, like changes in the food web due to overfishing.

Despite the odds stacked up against the kelp, I’m not giving up hope, and neither are the scientists who study it. They’ve created a Kelp Recovery Plan and continue to monitor the kelp forests. To help, we can all do our part, preventing runoff that heads to the Sound, and making sure our engines are working well to reduce carbon emissions and oily discharges. But perhaps the most important action is to remind our elected officials that, despite these uncertain times, kelp still matters.

Fresh water, even tidal fresh water, lacks something to me. It lacks the magic, the mystery of the plants and creatures that reside only in salt water. That’s why, despite its corrosive effect on my boat, I return without fail to sail in Puget Sound every year. Only here can I marvel at the juvenile salmon hiding among the blades or a grebe busily foraging. How much poorer would that experience be without the kelp forests that sustain these creatures? I don’t want to find out. I don’t think any sailor does.

Bruce Bateau

Bruce Bateau sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Ore. His stories and adventures can be found at www.terrapintales.wordpress.com