You won’t see the gull-sized Northern Fulmar in Elliott Bay, or as you pass Port Townsend on your way to the San Juan Islands; but once you take the turn at Neah Bay, you’ll see plenty.

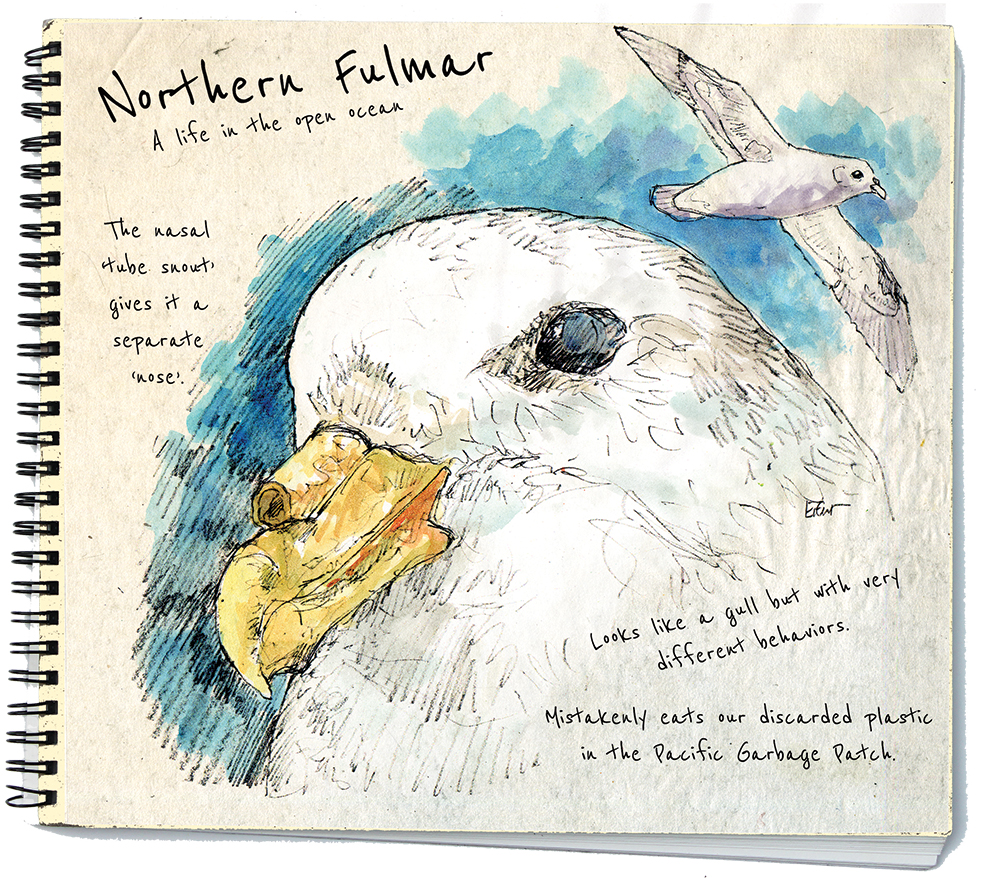

If you’re close enough, you may notice their unusual nasal passages positioned above the bill, which are called naricorns. Like gulls, they vary in color from white to gray or brown, but their behavior is very different with stiff wings and quick flaps to keep them airborne. Flying close to the water’s surface, they grab prey on the wing, or make quick dives for a morsel just below the surface. Fish, squid, and jellyfish are normal fare, but recently they flock behind seafood factory ships.

Fulmars use island sea cliffs to breed, gathering in large colonies to make primitive nests where the female lays one egg. Young take their time maturing and do not breed until they’re 10 years old, making them extremely vulnerable to changes.

We’ve all heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the two growing vortexes of plastics floating around the center of the ocean that is currently about 600,000 square miles in size. As all this plastic grinds together out there, it breaks up into ever-smaller pieces, and guess which birds pick up pieces thinking it’s food? Fulmars fly by and grab, then swallow. Some fulmars have been found to have dozens of plastic things in their stomachs: bottle tops, little plastic shards of bigger items, junk someone bought. While the plastic doesn’t digest, it does fill up a limited space in there, making it impossible for the bird to get enough to eat. Basically it thinks it’s always full which, I guess, it is. That plastic bag or water bottle that gets blown overboard or slides off a surface in a puff (or worse, is carelessly thrown over) — ALL will eventually get small enough to be eaten by wildlife. Maybe a little Fulmar.

We’ve all heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the two growing vortexes of plastics floating around the center of the ocean that is currently about 600,000 square miles in size. As all this plastic grinds together out there, it breaks up into ever-smaller pieces, and guess which birds pick up pieces thinking it’s food? Fulmars fly by and grab, then swallow. Some fulmars have been found to have dozens of plastic things in their stomachs: bottle tops, little plastic shards of bigger items, junk someone bought. While the plastic doesn’t digest, it does fill up a limited space in there, making it impossible for the bird to get enough to eat. Basically it thinks it’s always full which, I guess, it is. That plastic bag or water bottle that gets blown overboard or slides off a surface in a puff (or worse, is carelessly thrown over) — ALL will eventually get small enough to be eaten by wildlife. Maybe a little Fulmar.

Larry Eifert

Larry Eifert paints and writes about the Pacific Northwest from Port Townsend. His large-scale murals can be seen in many national parks across America, and at larryeifert.com.