Uncovering Climate Data and Sea Stories in the Logbooks of Early Mariners

By the time our boat reached the middle of Haro Strait, I knew that my husband Frank and I were in trouble. The weather report, checked at the dock before departure, had not indicated dangerous conditions and we were excited to begin our two-month circumnavigation of Vancouver Island. But in the Strait the wind was gusting 40 knots, opposing a strong tide and creating steep waves that foamed above our cockpit before slamming into our 26-foot boat on all sides. It was like cruising in a washing machine on the heavy cycle.

We quickly reduced sail and started the engine, which proved to be little help as breaking waves lifted our stern out of the water, causing the outboard to cavitate while the bow dove below the surface. Turning around seemed impossible, so we ducked behind the nearest island—more of a large rock, really—and waited several hours for the wind to ease. No wonder ours was the only boat in sight. “You were out there in this gale?” our neighbors asked as they helped us tie up at the dock in Sidney, B.C. “In that small boat?” For years I called that crossing our “shakeup/shakedown” cruise.

Since then, we have encountered more challenging conditions on much bigger water on many different boats. Yet this experience stands out. Although it happened 25 years ago, I recall that day vividly, not because I have an excellent memory but because it is recorded in our logbook, along with my repudiation of the misleading weather report.

Like 48° North’s columnist Dennis Bottemiller, I am an “obsessive” record keeper (see his column in the December 2024 issue). My logbooks are organized into sections, including weather, boat maintenance and repairs, wildlife encounters, and people met along the way. We modern cruisers have this in common with mariners of the past, who have chronicled life on the water throughout the centuries. While focused on weather and sea state, early logbooks also provide information on everything from diet to ship’s supplies to social interactions on board. Some of them even tell riveting sea stories.

Precious Cargo

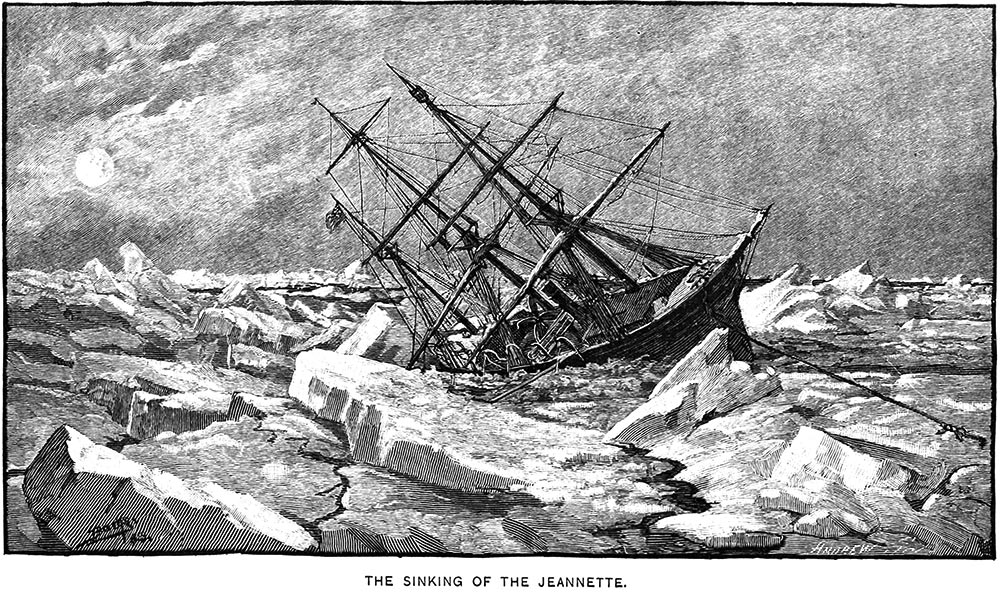

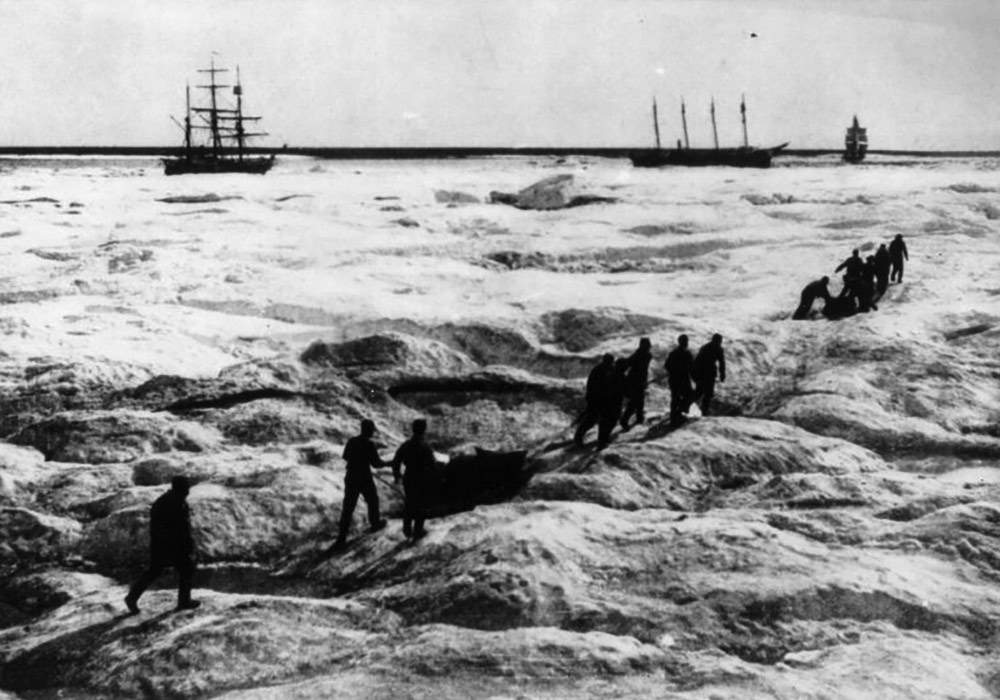

What is the most important portable item on your boat? What would you take with you if you and your crew had to evacuate? Maybe it’s equipment, water, food, or clothing. Ship captains of the past regarded their logbooks as indispensable. Naval officer George W. De Long, for example, spent his last days dragging the four volumes of his logbook across a frozen delta in 1881, hoping to lead the remnants of his crew to safety when their vessel, the USS Jeannette, sank after being trapped in Arctic ice for two years. Starving, frostbitten, and too weak to continue, Captain De Long buried the leather-bound logbooks, marking the spot with a pole before he died. Several months later, crew member George Melville discovered the logbooks during a search for his missing shipmates. Stumbling through a snowstorm, his legs swollen from exposure, Melville considered reburying the logbooks to lighten his load. Luckily for us, he changed his mind. “I would swear a new oath to carry them through . . . come what might,” he wrote [Andrew R.C. Marshall, “How the Secrets of 19th Century Ship Logbooks are Helping Scientists Understand Arctic Climate Change,” Arctic Today, Dec. 13, 2019]. Today, the logbooks of the ill-fated Jeannette and its voyage, the US Arctic Expedition, are preserved in a climate-controlled storage room in the National Archives.

The officers of the Corwin, a Pacific Revenue Cutter (predecessor of the US Coast Guard) based in San Francisco, displayed a similar, if less dramatic, resolve to preserve their record in 1881. Sent to search for the Jeannette, which had also left from San Francisco, the Corwin’s exploring party built a cairn on Herald Island in the Arctic Ocean, marking the spot where they placed a sealed bottle containing a record of their visit, along with a copy of the New York Herald. The Corwin did not locate the Jeannette or the missing whaling ships they hoped to find. Yet the crew, which included the naturalist John Muir, spent their voyage gathering data on weather, wildlife, glaciation, and other topics. Scientific exploration of the Far North often went hand-in-hand with colonial expansion—and ship captains were aware that protecting logbooks meant protecting their legacies.

While mariners had kept logbooks since ancient times, records became more detailed over the centuries, including geographic position, vessel speed, precipitation, wind direction and force, temperatures, ocean currents, sea conditions, and sightings of whales and other commercially valuable marine life. By the eighteenth century, maritime logbooks had become structured and standardized for legal and administrative purposes—and the British Royal Navy considered false or sloppy recording to be a serious offense. “Anything you read in a logbook,” claimed Clive Wilkinson of the UK’s National Maritime Museum, “is a true and faithful account” [Dan Drollette Jr., “Using Naval Logbooks to Reconstruct Past Weather—and Predict Future Climate,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Nov. 3, 2014]. The US Navy similarly held logbooks, also called deck logs, to rigorous standards of reporting.

Old Weather Project

Nearly three-quarters of the Earth is covered by oceans, which generate much of the planet’s weather. Around 2010, climate researchers in the UK discovered that old logbooks chronicling the sea voyages of the past were a treasure trove of information about marine conditions over time. “Mariners really care about the weather and have done so for centuries,” explained Philip Brohan, a UK climate scientist who appreciated the military precision and uniformity of Royal Navy logs. Launching the “Old Weather Project,” UK scientists mobilized volunteers to transcribe and digitize these largely forgotten records, entering details into a dataset that reconstructed global climate patterns.

Seattle scientist Kevin Wood joined forces with Old Weather after meeting Brohan in a pub. Wood brought in the resources of the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, which included the University of Washington and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). As part of this effort, he set up a team of volunteer “citizen scientists” to comb the logbooks of the US Navy and Coast Guard, housed in the National Archives and available online, for climate observations. According to NOAA, these “weather time machines” were key to constructing predictive models, which benefit modern mariners. Old Weather is one of several lines of investigation that NOAA used to create a profile of global climate over time, called the “Twentieth Century Reanalysis Project.”

“Every ship becomes part of our quest,” Wood commented in 2019. “Because the more data we have, the better the reanalysis will be.” The logbook of the wooden sloop-of-war USS Jamestown, for example, provided new observations helpful to understanding the “Sitka Hurricane” that hit the Alaska Inside Passage in October 1880. Moored in Sitka Harbor at the time of the storm, the Jamestown’s crew recorded hourly details about pressure, wind force, and water temperature from a vantage point directly affected by the storm, offering a comprehensive view of its intensity. The reanalysis revealed that the Sitka storm was not a hurricane, but part of a larger system called an extra-tropical cyclone. “Old Weather has got to be the most engaging project I’ve ever had the luck to work on,” Wood noted [Marshall, Dec. 13, 2019].

Stinking Fogs and Pleasant Gales

Reading, deciphering, and transcribing logbooks was central to the Old Weather Project, which ended in 2020. It wasn’t a simple task. Cracked and faded with age, many of the old volumes were handwritten in hard-to-read cursive. Individual letters in historical handwriting often include decorative flourishes or loops. The letter “s,” which sometimes looks like an “f” in old documents, has often confused me, and the number “7” can easily be mistaken for “4.” Yet the organizers of Old Weather preferred human readers over optical scanners, believing them to be more accurate, especially when checked several times by multiple people.

Archaic terms in early logbooks can also bewilder modern readers. The recordings of Captain George Vancouver, a British naval officer who explored the Northwest Coast, included multiple definitions of the word “gale” in the log of his expedition to the area. One passage dated 1792 described a “gale of wind” that “blew during the night with great violence,” while others mentioned “gentle” and “pleasant gales” of “very light airs.” In my own logs recording the weather in the same area of the B.C. Coast, the words gale, gentle, and pleasant never occur together.

Vancouver’s descriptions predate the Beaufort scale, a system for estimating wind speed and its effects, initially on the sails of a man-of-war. British Royal Navy officer and hydrographer Sir Francis Beaufort developed the scale in 1805 based on observations aboard the HMS Woolwich. The Royal Navy adopted the Beaufort scale in the 1830s, standardizing wind force terms for sailors.

For all their rigor and accuracy, early logbooks contain plenty of human sentiments. Early European mariners sailing the Northwest Coast reveal a variety of emotions in their descriptions of weather: frustration, disappointment, and fear. Sir Francis Drake, who may have reached as far north as the 48th parallel in his sixteenth-century explorations, reportedly found the rain of the Pacific Northwest to be “an unnatural congealed and frozen substance,” followed by “most vile, thicke and stinking fogges.” According to my own log, a similar observation led to the installation of radar on my 26-foot boat. Vancouver’s crew, too, was given to editorializing when recording the weather, complaining that the expedition’s ships were “harassed with a foul wind,” strong currents, and “very gloomy disagreeable weather.”

Logbook Lore

Some logbooks offer compelling stories with relatable characters, which come through more vividly in the original longhand. “There is a deeper connection when reading something handwritten than when reading the same information in print,” one Old Weather volunteer explained. “Reading the various entries is almost like hearing individual voices…This is real. A real person saw this and wrote this.”

Another volunteer agreed, adding “the stories are just so astonishingly epic.” She transcribed the logbook of the Rodgers, which sailed from San Francisco in 1881 in search of the Jeannette. While the Rodgers managed to evade the ice that destroyed the Jeannette, the rescue vessel ultimately succumbed to a fire in the Arctic. While the crew and the logbooks were saved, the ship’s dog “One-Eyed Riley” perished in the flames. “He probably would have ended up in the pot anyway,” the volunteer suggested. “Snoozer,” the last sled dog aboard the Jeannette, met a similar fate, providing protein in a “nauseating stew” for the starving crew. These tales reveal the miseries that everyone on board endured.

The fate of Charles Putnam, the Rodger’s 29-year-old master, was particularly heartbreaking. While searching for the Jeannette ashore with two sleds and a year’s provisions, Putman attempted to return to help his shipmates when he heard about the fire that destroyed their ship. A sudden storm separated him from the rest of the party, and Putnam drifted out to sea on a chunk of ice, beyond rescue. He was last seen floating several miles offshore. “It traumatized me for some time,” said one transcriber after reading Putman’s story [Marshall, Dec. 13, 2019].

The logbooks of the Revenue Cutter Bear also yielded dramatic tales along with marine observations. The ship’s best-known captain was a hard-drinking sailor named Michael Augustine Healy, also known as “Hell Roaring Mike” in Alaska lore. Born in Georgia, Healy was the son of a plantation owner and a slave. In the twentieth century, the US Coast Guard recognized him as the first African American to command a federal ship. But during the late nineteenth century, his notoriety stemmed from his reputation as a “tamer of America’s sea frontier,” as Healy was known for his daring rescue of shipwrecked sailors, delivery of mail and medicine to remote regions, and apprehension of smugglers and poachers. Healy, who had commanded the Corwin early in his career, inspired author Jack London’s adventure stories of the Far North.

It is amazing to think that the low-tech logbooks of centuries past have helped improve modern weather forecasts, leading to useful, sophisticated tools like PredictWind and WindAlert. And while many of my friends now keep their boat records electronically, I have not given up on my handwritten, water-stained, dog-eared logbooks, some of which include my drawings and memorabilia (such as the dollar bill a friend once jokingly tossed into my mandolin case when I was playing at the dock). Every entry takes me back to the time, place, and sea conditions of my adventures, and I get a glimpse—for good and bad—of the sailor I used to be.

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and meticulous record keeper residing in Seattle. Navy logbooks housed in the National Archives can be viewed here: https://www.archives.gov/research/military/logbooks/navy-online-thru-1940