After cruising the British Columbia and Alaska coasts for more than 40 years, we’ve reached the conclusion that some of the best cruising lies just north of Cape Caution. The problem is getting there, and then successfully rounding this notorious promontory.

British Columbia’s Cape Caution is at the southwest corner of the British Columbia mainland across Queen Charlotte Strait from the northern tip of Vancouver Island, where the more protected waters east of the island meet the Pacific Ocean.

Cape Caution is intimidating to many boaters, due in no small part to its reputation. Its notoriety is well earned—it is a significant cape that is exposed to Pacific Ocean swells arriving from hundreds of miles away. Rounding the cape is demanding, with challenges that include complex currents, strong winds, and frequent fog. A voyage to this cape should be founded on a few years of previous experience cruising southern waters.

The distance to Cape Caution from the Canada/U.S. border in Haro Strait is about 250 nautical miles. In a typical 35-foot sailboat, it will take about 10 days to get there. If time is limited, you should plan to travel at least 40 miles a day, allowing for two or three port stops if needed. Planning is critical, for there are few places to fuel up or buy provisions between Campbell River and Port McNeill. Marine parts are also scarce, so be sure to bring spares such as oil filters, pulley belts, impellers, and light bulbs—parts most cruisers already carry.

Other obstacles to reaching Cape Caution include the major passes and rapids north of Campbell River. Although most chartplotters will have tide and current information, we always carry printed copies of the Canadian Tide and Current Tables as well, which are available free online at: charts.gc.ca/publications/tables-eng.html.

Boaters must have the proper Canadian charts (paper as well as electronic is best) and should carry the Sailing Directions for the British Columbia coast up to Fitz Hugh Sound. Various volumes of the SD are available at the above-noted website and paper charts can be purchased at most chandleries.

Route to the Cape

Let’s start with the Strait of Georgia and a brief summary of the route we take to get to Cape Caution. If you’re traveling in a sailboat with a hull speed of under six or seven knots or a slower trawler, try as hard as you can to coordinate your travel with the tides. The flood tidal stream flows north in Georgia Strait until it meets the opposing flood current flowing south from Discovery Passage, about five miles south of Cape Mudge.

Let’s start with the Strait of Georgia and a brief summary of the route we take to get to Cape Caution. If you’re traveling in a sailboat with a hull speed of under six or seven knots or a slower trawler, try as hard as you can to coordinate your travel with the tides. The flood tidal stream flows north in Georgia Strait until it meets the opposing flood current flowing south from Discovery Passage, about five miles south of Cape Mudge.

We try to arrive at Campbell River just as the north-flowing ebb in Discovery Passage is getting underway. Our preferred route heading north is Discovery Passage through Seymour Narrows. The pass is free of any obstructions and the only challenges are the currents—which can ramp up quickly to double digits—and commercial traffic such as tugs or cruise ships.

To transit this pass, we time our morning arrival at Seymour Narrows as the current is changing to a positive flow, which is the north-flowing ebb. This way you’ll make good time getting to some nice anchorages at the top of Discovery Passage, such as Kanish Bay on Quadra Island or Handfield Bay on Sonora Island.

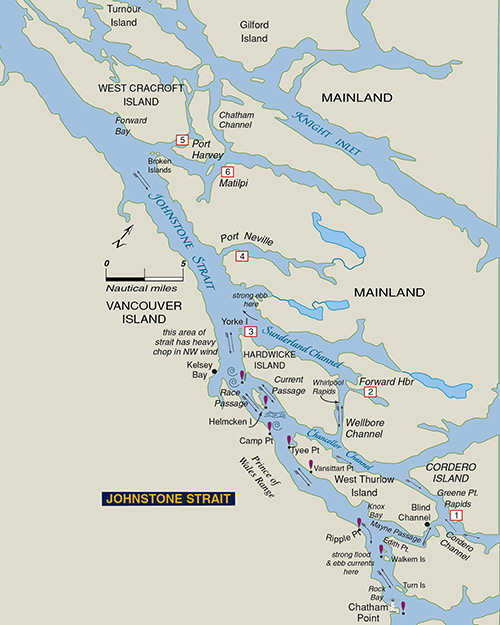

Once you’re in the proximity of Chatham Point, you’re at the mouth of Johnstone Strait—a rite of passage for boaters trying to get north. After you’ve had a few tussles with this strait’s often very strong breeze, you’ll understand one thing about northern voyages; none of them are easy.

The best way to master Johnstone Strait is to outfox the winds and, as with any fox, the key is to make your move either early in the morning or in the evening. Normally we try to leave our anchorage no later than seven in the morning. If the weather is sunny, westerly winds will often pick up by around nine o’clock and can be anywhere from 5 to 35 knots by noon. It’s always wise to stay up-to-date with the typical slate of weather forecasting resources, but the previous day’s winds will also be a good indicator of coming wind strength, and monitoring the VHF weather station at Chatham Point will give current conditions in the strait.

Getting from Chatham Point to Port Harvey is the goal and, since ebb current in Johnstone Strait flows in a northwest direction, catching an ebb will be very helpful, especially if the weather is fair so the impact of breeze-against-current will be reduced. This can be a nasty stretch of the strait so make as many miles as possible if conditions are good. Stay to the north side of the strait to get the most of the ebb.

There are places to duck out of the wind if things get too hectic, including Mayne Passage and the resort at Blind Channel or, a little farther north, Forward Harbour. There are passes in this area, including Current and Race Passage as well as Wellborne Channel and Whirlpool Rapids.

We often pull into either Port Neville or Port Harvey on the north side of Johnstone, but some of the strongest winds and steepest chop can be near Kelsey Bay on the south side, which, with its public dock, is another spot to seek refuge from poor conditions in the strait.

The objective is to get through Johnstone Strait quickly and arrive at either Port McNeill or Port Hardy, both of which have good moorage and fuel facilities. These towns, roughly 20 miles apart on Vancouver Island, are our regular provisioning ports before heading past Cape Caution. Some boaters like to meander through the Broughton Archipelago and go up the mainland side to Blunden Harbour, which has no facilities but is a beautiful anchorage.

APPROACHING AND ROUNDING CAPE CAUTION

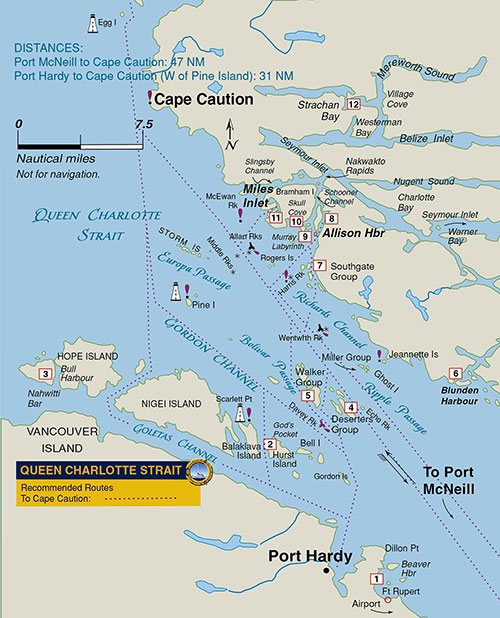

From Port McNeill, it’s about 45 miles to Cape Caution, but just a few miles south of the cape are some excellent anchorages where we sometimes stop to wait for favorable weather conditions or just enjoy the scenery. These include Allison Harbour, Murray Labyrinth, and Miles Inlet, all of which provide excellent shelter. Allison Harbour is easy to enter and large enough for several boats.

From Port McNeill, it’s about 45 miles to Cape Caution, but just a few miles south of the cape are some excellent anchorages where we sometimes stop to wait for favorable weather conditions or just enjoy the scenery. These include Allison Harbour, Murray Labyrinth, and Miles Inlet, all of which provide excellent shelter. Allison Harbour is easy to enter and large enough for several boats.

But the penultimate challenge upon leaving Port McNeill is getting across Queen Charlotte Strait, which is easier said than done. Westerlies can quickly build and the other hazard is fog, which is common from late July to September and can persist daily into early afternoon. If fog or strong winds begin to develop and crossing the strait is not practical, there are several options to get out of the weather, such as anchoring in the lee of Peel Island in Beaver Harbour or pulling into Port Hardy. Another option is the Walker Group anchorage in the channel between Kent and Staples Islands.

You can get an idea if the day’s conditions are favorable for rounding Cape Caution from the reported wave height at the West Sea Otter buoy: if this is below one meter, the trip will be safe and relatively comfortable. We can attest to this. If higher than one meter, it usually means the wind has picked up and your boat will be rolling quite a bit past the cape as you head to Egg Island. West winds above 15 knots would also make us think twice and probably result in heading to an anchorage on the mainland side.

There are several routes to the cape. The most direct route from Port McNeill is a line from Malcolm Island that goes between the Deserters Group and Echo Islands. This will take you close to Allan Rocks, which is a good waypoint, being near the entrances to Allison Harbour and Miles Inlet—great anchorages to pull into if conditions have deteriorated.

Another route for boaters wanting to avoid mainland current is plotting a course near Pine Island, following either Gordon Passage or Europa Passage. This route does, however, limit your options for ducking into a mainland anchorage in poor conditions.

The state of the tide is another factor. If a strong ebb is under way, the current coming out of Slingsby Channel will be significant and, if a west wind is blowing, the chop will be brutal near the entrance. Stay at least a mile or two off Fox Islands under such conditions.

When approaching Cape Caution for the first time, boaters are well advised to keep a mile or two off the cape, even in settled weather. The bottom shelves quickly opposite the cape and can create conditions the cape is renowned for – steep sweeping seas as wind goes against current.

We used to sail west of Egg Island for a look at the lighthouse which is doable, but now we stay on the east side to get out of the waves and rolling seas. We also stay west of North and South Iron Rocks. Once past Egg and Table Islands, things slowly begin to moderate and you can lay a course for the cruising paradise of Fitz Hugh Sound. If conditions are worsening, a good nearby anchorage is Jones Cove in Smith Sound or farther east to Indian Channel or Takush Harbour.

Many boaters like to turn into Rivers Inlet, or go farther north to Penrose Island Marine Park and the anchorage north of Fury Island. If a strong southwest wind is forecast, Safety Cove is a good spot to anchor. Beyond this lies a myriad of beautiful destinations, including Pruth Bay and Fish Egg Inlet.

Either way, congratulate yourself, you’ve made it around Cape Caution—an accomplishment in itself and a gateway to some of the world’s finest cruising grounds.

Award-winning authors William Kelly and Anne Vipond have written about cruising the B.C. Inside Passage for over 40 years. Their stories have appeared in yachting publications across North America. Their best-selling and award-winning guidebook Best Anchorages of the Inside Passage—recently released in a revised second edition—covers anchorages from the Gulf Islands to Bella Bella and includes Desolation Sound and Broughton Archipelago. The book also covers pilotage to all the tidal passes leading to Cape Caution.