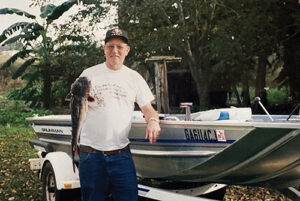

My Uncle Jess was a tried and true powerboater, squeezing every usable ounce of function from his Chris Craft for fishing trips on San Francisco Bay or a water skiing adventure on Lake Berryessa, a large man-made reservoir not far from his home in Northern California.

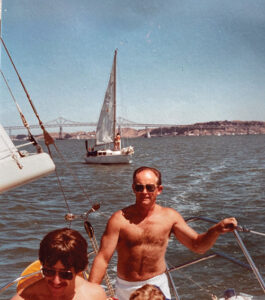

My father, on the other hand—who at one time wasn’t a boater at all, but rather a weekend pilot—became more interested in sailing than fishing or waterskiing. He traded in his small Piper airplane for a Catalina 36 as a means to enjoy his retirement and spend more time with family and friends, reveling in the challenges of learning to capture the wind instead of Pacific salmon.

While my dad and his brother-in-law rarely argued about the superiority of sails versus engines, it’s a discussion that plays out again and again in the clubhouse and on the dock of my local yacht club. Though my experience is comparatively limited—this column is about my newcomer’s perspective as I launch into adventures on the Salish Sea, after all—I’ve recently gotten in on the action. It seems I’m amending, or at least evolving, my previously one-sided viewpoint. Each person’s preferences, tastes, and opinions on this topic should be respected and are inherently unique; the ones I’ll express below very much included. But mainly, it’s just plain fun to explore the relationships between different kinds of boats and the people who use them.

Since I followed in my dad’s footsteps by purchasing a sailboat a few decades after he sold his Catalina, I have been backing the sailors in the debate of which boat is better. But since selling our Columbia 28, Ariel, I have spent a number of afternoons aboard a 22-foot powerboat with a 150 horsepower engine. I must sheepishly admit that it didn’t take long for me to appreciate powerboating’s merits, despite memories of some rough and tumble excursions aboard my uncle’s vessel when I was younger. Accepting this adjustment of my perspective, though, has not been easy.

Lake Berryessa.

Growing up near San Francisco Bay, I often saw the romantic vista of sailboats dotting the Bay as I crossed the Golden Gate Bridge on a sunny afternoon. Like an Impressionist painting, the boats seemed frozen in time, yet still conveyed the energy of dancers in their balance between the wind and waves, leaving only a trace of froth in their diminutive wakes.

Setting aside the nostalgia of early morning fishing trips or lazy afternoon sails, the advantages and benefits from each type of boating really depend on conditions—including those of the boat itself—as well as the intended use-case and the point of view of the observer.

It’s not uncommon for sailors to claim that a sailboat is elegant and romantic. But if a vessel has more than a few nautical miles in its wake, then it might be regarded as either classically vintage or perhaps a bit tired, depending on its level of maintenance and care.

As my experience with powerboats increases, I find that they too, can be attractive, sleek and sexy; except those designed for fishing or other heavy work, then their aesthetics strike me as unsurprisingly practical and utilitarian.

No doubt, sailing can be captivating and enchanting. But when an outing takes place in difficult conditions, the resulting experience may be uncomfortable and maybe a little frustrating.

Similarly, powerboating is often fun and exciting, except when it occurs on a craft that needs some attention, in which case it may be a little noisy, bumpy, and smelly. And though many powerboaters will be able to take refuge from the elements while driving, like sailing, difficult conditions create their own challenges for these vessels and mariners.

Granted, my comparisons and descriptors are oversimplified, but like most generalizations, there is a kernel of truth to support them.

While I don’t believe that the battle for the best kind of boat is rooted in romance and nostalgia, both of those areas can play a role in a boat owner’s preference.

In my personal experience with boating, I have found that the balance between forces and resources like time, money, and the elements can make or break an outing aboard either a sailboat or powerboat. I know that I am not alone in the belief that there is a sweet-spot to boating—a point when ability meets challenge and design matches conditions, regardless of whether the power source of the vessel comes from wind or combustion.

With sailing, I occasionally found such balance with sail trim. While I am no expert at setting and juggling the variation in sheets or other sail controls from the backstay to the downhaul, I did find that an ideal relationship between the jib and mainsail made steering a breeze, and course alignment steady.

As I increase my experience with small powerboats, I am discovering a sweet-spot with regard to speed, which is dependent on the throttle rather than the adjustment of the sheets and halyards. The shift from plowing at low speeds to planing at higher ones demonstrates the obvious correlation to velocity. However, speed also seems to affect how the boat cuts through waves and swells, not to mention the rate of fuel consumption.

In a training session with our new boat-share club’s captain, I was reminded to cut across swells at an angle, and even reduce speed aggressively when moving through larger waves. I recently discovered the reason for the technique the hard way when my failure to throttle back as I cut across a large wave resulted in an airborne jump and a startling slam for me and my on-board guests—an event which never occurred on our masthead sloop.

But I’ve also noticed that an uncomfortable resonance effect can increase the lift and drop of a powerboat when the speed matches the frequency of the wave. Changing that speed, either slower or faster can eliminate the aggressive leaps across the water, but as yet, I’ve been unable to find a formula for this condition-dependent sweet spot. For now, a reduction of speed is my go-to solution to alleviate the rough ride, but I’m planning to experiment with an increase in velocity sometime in the future.

In addition to rough rides, I’ve experienced another frustration with the speed of a powerboat, or more specifically the issue of control while keeping speed low.

On a sailboat, I find that the rudder provides ample control even when crawling through a marina at every speed (greater than 0.0 knots). While it took me a while to learn how to maneuver our three-and-a-half ton Columbia sailboat into her slip comfortably and without incident, I eventually understood that the momentum of the heavy vessel allowed me to “coast” into the marina about 50 to 100 yards before coming to a slow stop.

As I familiarize myself with small powerboats, I am learning a simple, obvious fact that anyone who has piloted these boats takes for granted. The pivoting prop provides control, eliminating the need for a rudder. But for me, that means that a powerboat in neutral has no turning ability, even if it has way on. No power equals no steering.

However, I am slowly learning to use the engine as a steering device, employing the rapid response of reverse to avoid minor collisions with the dock and, god forbid, another boat in the marina.

Among the various pros and cons, simply put, going fast is fun, even if speed is achieved through wind power, which is another element of the sail-power debate. Owners of cruising sailboats brag about “flying through the water” when they achieve speeds more than 7 or 8 knots. Famous mockumentary reference notwithstanding, one of the racers in my club even proclaimed the feat of achieving high speeds by naming his vessel, Goes To Eleven. Compared to my Columbia 28’s max hull speed of 6.2 knots, that’s quite impressive. But the 22-foot powerboat I’ve been using plows along as a displacement vessel at that speed and seems begging me to let it break free even when she is cruising at a comfortable 22 knots.

Speed comes with a price, though. I think I topped off my sailboat’s 12-gallon tank once a year, since the 9.9-horse Yamaha outboard merely sipped fuel at its cruising speed of 3 or 4 knots. But every hour traveling at high speeds in a powerboat requires about 7 or 8 gallons, at least. And in discussing the topic with owners of much larger powerboats, I consider myself lucky to consume even that modest quantity.

There is one area in which neither sailboats nor powerboats have an advantage, and that is the issue of maintenance. I don’t think there is a boat owner alive, regardless of their vessel’s default power source, who is not at one time or another frustrated and annoyed at the amount of time, money, and effort required to keep their boat in proper working order. Sailors have the added component of rigging and canvas. Powerboaters have more engine functions to care for and perhaps more systems as well.

Despite my personal oversimplifications, considering the array of challenges and disadvantages in balance with the ample rewards and benefits of various boat types and designs—I’m far from ready to settle the debate of which vessel is better, sailboats or powerboats. At the moment, thanks to my time aboard both types of boats, I’m not really sure which one I’d choose given the opportunity.

One thing is for sure. If I ever win the lottery and my ship comes in, I think that I’d just take one of each.

David Casey is a retired math teacher, and woodworker. After relocating from California, he and his wife Laura enjoy exploring the vistas of Puget Sound from the deck of a boat or a promenade along its shores.