Doug Fryer was a giant of Pacific Northwest sailing. Sail on, Doug, you will be missed.

In April 2020, the Pacific Northwest sailing community lost a legend. Much could be, and has been, written about Doug Fryer’s prolific career on and off the water. Below, we’ll share a biographical article Andy Schwenk penned early last year (it was published in the February 2019 issue). But before we get into the article, we wanted to share personal messages from two people close to Doug:

First, Andy Schwenk, author of the article below, had this to share with the 48° North in light of Doug’s passing:

From the moment I met Doug Fryer in Victoria at the start of the 1984 Maui race, we became fast friends. As the years went by and my father passed, Doug and men like him played an important role in my life. His ability to see simple truths and the beauty we sailors understand is unmatched.

Here I am delivering a boat north out of California as Doug did aboard Adventuress in the late 1950s. Differences are many. He was a teenager, and endured winter weather, gales, flooded berths, and the like. The sails were carried away early on and they never shut down the engine. Now, I write this aboard a vessel with gadgets he likely never dreamed of—an alphabet soup of GPS, EPIRB, AIS, DSC, and the like. Doug spotted Cape Flattery and, as the sole occupant still standing, brought her home safe. Of course, all of us wish the same for every mariner.

Doug was one of a kind. I sailed with him aboard Night Runner waist-deep in white water through Race Rocks as the 1.5oz spinnaker blew up. Doug directed me forward with the 2.2oz with wire luffs. Soon, we were back underway and headed for victory.

Doug had a clan that followed him. A crew jacket was his armor, always black, always salt-stained with equal parts sweat and seawater. Captain Fryer was at the helm in a courtroom, in a yacht club or social gathering, and certainly aboard his beloved Night Runner. Pour yourself a spot of Lemon Hart 151 rum, a touch of honey, and a splash of hot water from a battered teapot. Take your time. Tell your crew how special they are to you and how lucky each one of us is. Put your hand on the galley rail and thank the designer and builder for bringing the clan in safe. That was Doug’s way.

~ Andy Schwenk

Second, renowned PNW designer, Bob Perry, reached out and invited us to share his remembrance of Doug, which he originally posted on his fan club Facebook page.

My friend, my client and my attorney Doug Fryer died this weekend. About six months ago Doug called me on a Saturday and said he wanted to do a new boat. Music to my ears. Sunday evening he called and said he had some bad medical news and would have to put off the new boat. I kept working on the design anyway. I thought it might cheer him up and it did momentarily. But the writing was on the wall and the doctor’s prognosis accurate. Unfortunately.

The last race I did with Doug was last summer. Doug was a bit weak but he drove the entire race and we took 2nd. In classic Doug style, after the boat was put to bed the rum bottle came out with the hot buttered rum mix and the crew sat around the cockpit drinking “Ritual Rums”. Doug like 151 proof rum because it weighed less for the punch. We drank and Doug recited nautical poetry, some a bit bawdy. Doug had a resonant, baritone voice and he delivered the poems with attorney like panache. Looking back I think all of the crew knew we were experiencing something that would never happen again.

Doug was the “co-inventor” of the Life Sling system. He did not take a nickel from all the units they sold. It was his gift to sailing.

I could tell Doug and Night Runner stories all day. Doug loved sailing and he loved Night Runner. When he first came into my office he showed me a magazine clipping of a Bruce King design and asked me if I could “fix” it.That did not sound like fun to me so I convinced Doug to let me draw a preliminary design for him. He said “Fine I’ll come back Tuesday.” It was Friday. Monday morning, early, I stared at the blank sheet of vellum and racked my brain for an idea. Nothing. I re-racked. Nothing. I couldn’t just regurgitate the Bruce King design. I had way too much pride for that. Then it occurred to me that people usually like what they know. Doug’s current boat was the venerable Atkin cutter AFRICAN STAR. The worm in the race fleet was, “If you can see African Star at the finish, they have beaten you.” I drew a 42-foot, fin keel version of African Star. Doug showed up on Tuesday, took one look at the preliminary drawings and said, “I like it.”

Doug won the Swiftsure Race seven times in Night Runner. I can remember being knocked on our beam ends, chute up going through Race Rocks one year. Doug was awarded the CCA Blue Water Medal for his voyage around South America and rounding Cape Horn. Doug raced Night Runner in the single handed TransPac. Night Runner had some nick names, Night Crawler, The Mayflower. It is one of the finest feeling boats I have ever sailed.

So now what? Wish I knew. I have this feeling that it’s the end of an era in PNW yachting. It will be interesting to see what happens to Night Runner now.

So long Doug. It was an honor.

~ Robert Perry

In addition to enjoying these messages and the article below, please visit Doug’s memorial page at Evans Chapel’s website. There’s a guest book and photo album where friends of Doug can share memories with his wife Karen and the rest of his family.

Now, here is Andy’s article about Doug:

Doug Fryer: A Legendary Pacific Northwest Sailor

Doug Fryer: A Legendary Pacific Northwest Sailor

by Andy Schwenk, from the February 2019 issue of 48° North.

“I have had the pleasure of sailing and winning Swiftsure twice aboard Night Runner in recent years. I’d like to take the credit, but Doug has 50 Swiftsures under his Sou’wester, so he oughta know the way.”

When the definitive book on sailing is written of sailing in the great Pacific Northwest, it will of course have the story of the oldest competitor ever to win a sailing gold medal gold medal in Olympic competition: Bill Buchan, and the rest of the Buchan family sailing dynasty. Larry Ellison may figure prominently, because of his contributions to the modern America’s Cup in the form of multihulls built in Anacortes, WA. The seventy-footers that have set and broken most of the course records—like Diamond Head, Atalanta, and Neptune’s Car—will have pages about them. No such book would be complete without the story of Doug Fryer, whose accomplishments are vast and whose influence as a sailor in this region is immeasurable.

Doug’s Early Years

Imagine growing up as Doug did: in Portage Bay with World War II raging all over the world; and lying at anchor outside your bedroom window is the Guinness family’s yacht, Fantome. (I guess the Guinnesses figured that providing beer for the troops when they came home from the war was their contribution and the British government was not going to requisition their yacht for the war effort. Fantome sailed until 1998 when she was lost during Hurricane Mitch with 31 souls aboard – a sad story for another day.) How could young Doug not have dreamed of glorious sailing adventures with that boat right outside?

Doug pedaled his paper route and attended Lincoln High School, and he also affixed labels on steel products his father produced, earning a dollar a day. Eventually, he saved enough money to purchase his first sailing vessel, the Little Dipper—an 18’ Flattie. He competed in the Lake Washington fleet until, one December, he capsized while planing north in a southerly gale. The mainsail held the boat flat to the water and each time she rolled upright, the wind would blow her over again. Doug finally decided to swim to the masthead to lower the main. This time, she rolled up right and, with no sail to hold her flat, she simply inverted, sending the centerboard out the top of the trunk and leaving Doug pacing on the bottom of the hull. He was eventually towed to the Laurelhurst Beach Club and decided it was time for a bigger boat.

Off to Sea, But Busy at Home

Doug took a gap year after high school in 1952. During the winter of this year, he shipped aboard the Gracie S, a 97’ schooner owned by Ed Kennell and later by Sterling Hayden. His voyages aboard the Gracie S included three passages to Hawaii and his first trip to Alaska.

In his shore time, Doug worked at Fisheries Supply, where he specialized in splicing. One summer, he and a pal turned out 500 logger’s slings made of 5/8 cable, requiring 1,000 splices total. They could make a sailor splice in 15 minutes, which required 5 1/2 tucks. The more complex logger’s splice was harder to unravel, required a complex burying technique, and 6 1/2 tucks. In spite of these other pursuits, Doug still found time to work at Robert Broom’s sail loft in Ballard. Robert’s father had mostly made sails for square riggers, but Doug was routinely assigned hatch covers and life boat tarps. As if he wasn’t already busy enough, he found time to prepare himself for his pursuit of a law degree.

Doug’s second vessel was an ex-surf-boat he made into a schooner, the Altair. This boat did for him what similar vessels have done for many sailors early in their careers – it taught a tough lesson and yielded the wisdom to say, “I’ll never do that again.” After pouring his entire savings and countless hours into her resurrection, he sailed her once and promptly sold her at a huge loss.

Epic Adventuress Voyage

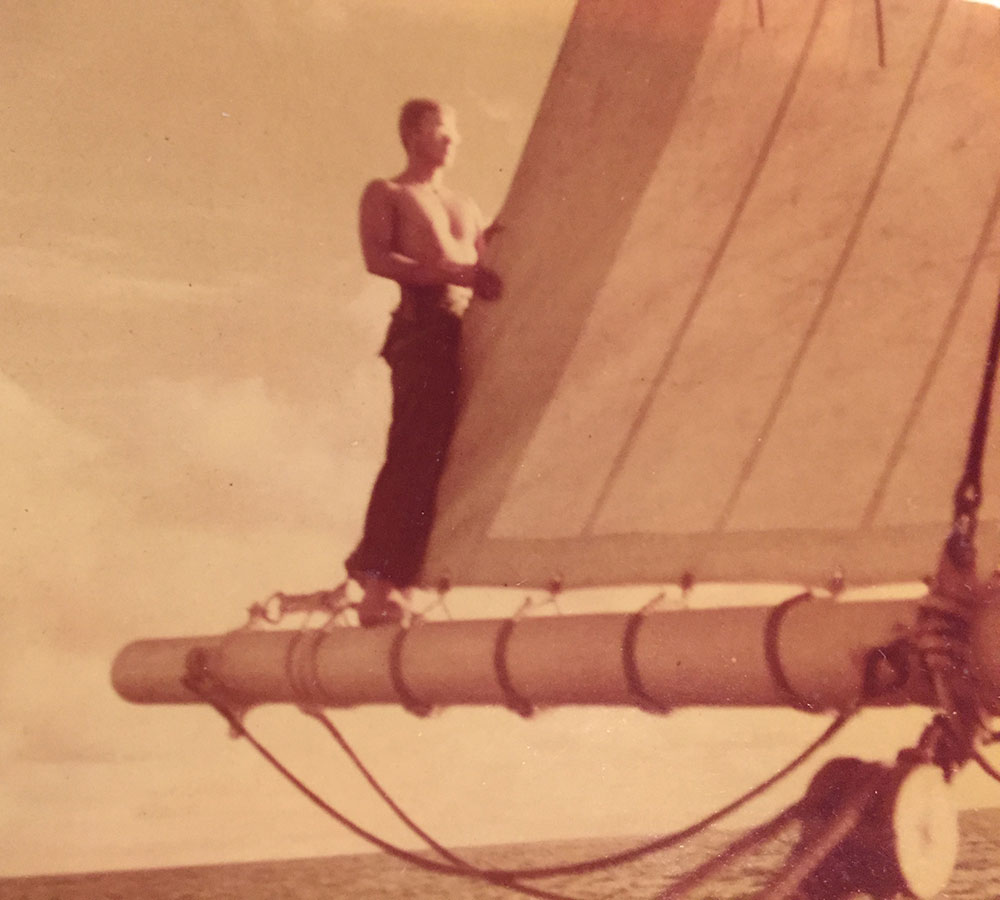

While aboard the Gracie S in the Bay Area, Doug received word that the local sailing chandlery legend Doc Freeman had purchased the 133-foot gaff-rigged pilot schooner, Adventuress; which is still at work locally to this day. Doc hired Doug to help bring her north.

The Adventuress was different then. She had stumpy masts and a doghouse aft, which suited her employment by the pilots association in San Francisco. Doug, just 18 at the time, was the only real sailor besides Doc in the crew of six. To say the northbound delivery was a rough trip is an understatement. It was downright harrowing. The sails were blown to pieces the very first night. Huge seas kept the pumps running round the clock. The 6-cylinder Atlas was running ok, but the transmission was gimpy and the heater created toxic fumes and had to shut down. Doug was often at the helm alone. The vessel rolled heavily with no sails to steady her, and Doc took a fall and fractured some ribs. Using lighthouses for bearings and the distance-speed-and-time formula, Doug continued north. Eventually, Doc recovered enough to split four-hour watches and they made it into Seattle with three crew still in their bunks, where they had been for the duration of the trip.

New Boat and New Adventures

Upon his return, Doug purchased his third vessel—a former Bristol gillnetter with a catboat sprit-sail rig, similar to what you would see on a Sunfish today. There were literally hundreds of these boats on the Columbia River before the dams; and when the bottom fell out of the salmon market there, they eventually made their way to Alaska. He purchased her for $500 and christened her Altair. The 30-foot flat-bottomed, centerboard boats could carry several tons of salmon and still just scream on a reach.

It was about this time Doug and a pal hatched a plan to make some quick cash. Rumor had it the military had been using an outcropping of rocks near Skipjack Island in the San Juans for bombing practice. As Doug understood it, the bombs had prodigious amounts of lead in them, and they figured it would be child’s play to simply gather it up and sell it for a tidy profit. They traveled to Deer Harbor with an outboard of their own, where they “requisitioned” a dormant reef net boat for use in this foray. It was winter, so they had jackets, but as was Doug’s custom, they had no lifejackets (I’ve never seen him wear one). As it turned out, the weather was rougher than they planned for and the boat leaked quite a bit. The outboard soon failed, so they were at the mercy of the wind and tide. They bailed through the night and eventually went aground on the eastern side of Waldron Island. Their dreams of financial success were doomed anyway, as they discovered the bombs were made of iron, not lead. They did, however, eventually get the outboard restarted and returned to Seattle hat-in-hand.

Doug has always liked to sail fast downwind. He had his heart set on being a member of the “Pipe ‘n’ Bottle Club”—some exclusive fraternity of the crew of the Gracie S. In an attempt to impress his shipmates, Doug and a pal cleared the Ballard Locks in a dory bound for Pt. Monroe. News reports of the day claimed the wind pegged the meter at 89mph. Of course, it was a southerly—and Doug, his pal, and the dory were blown ashore in Kingston where they spent a night on a garage floor left open because the wind blew the door off its hinges. I forgot to ask if he earned membership into the club, but I don’t see why not. Doug said the dory never shipped any water which was fortunate since, as usual, they didn’t have lifejackets.

Design Inspiration for Night Runner

As his professional career as a maritime attorney took off, Doug purchased the African Star, a 34-foot Atkin cutter. With the African Star, he competed in two Vic-Maui Races, and also fell in love with cruising in the Queen Charlotte Islands.

As the 1970s waned, Doug decided he wanted to have a wooden boat designed and built. He had heard of the Bruce King designed wooden sloop, Unicorn, in Los Angeles and flew to see her. At this time, Bruce was famous for the Ericson 39 and Doug thought this could be the design he wanted. He was so impressed, he had his builder, Cecil Lange of Port Townsend, fly down as well to have a look for himself. Around this time, Doug read a review of the Valiant 40 designed by Pacific Northwest legend, Bob Perry. The Valiant 40 was Bob’s first design featuring a “break” between the rudder and keel. Doug knew he wanted a similar skeg in front of the rudder on his vessel, and commissioned Bob to make a sketch of the vessel that would eventually be Doug’s final yacht, the now-famous Night Runner.

Coincidentally, Bob was supposed to have sailed aboard the African Star before Doug ever owned her; and on this occasion, Bob sat aboard her one rainy evening waiting for an owner that never showed. When Doug told Bob he wanted a boat that looked similar to African Star above water, but with a modern underbody, maybe Bob remembered that night.

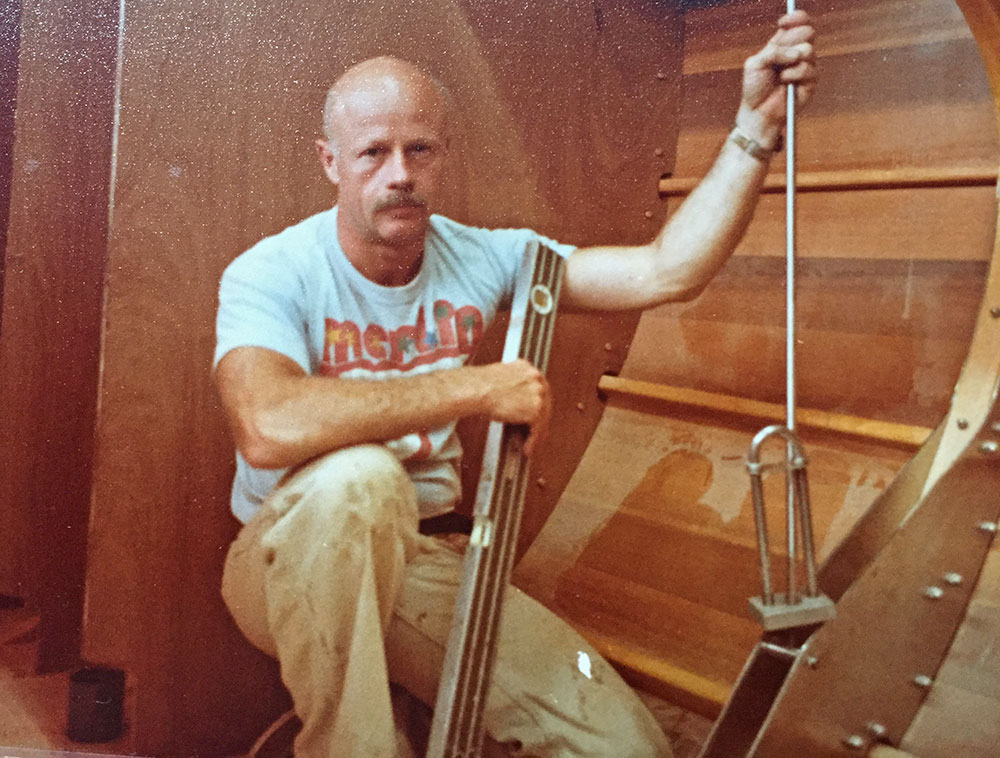

Building and Launching Night Runner

Once the Night Runner build began, Doug spent every spare moment he had over the next 18 months assisting at Cecil Lange’s yard in Port Townsend. There is a rumor that once a tool was turned on in the morning, it was not shut off until work was completed for the day in order to complete the build as expeditiously as possible. Doug was the king of the unskilled labor department. He pushed brooms and held the dumb end of measuring tapes, in order that the skilled folks could concentrate on the tricky stuff. To his credit, he did do all the plumbing, varnishing, and mounting of the deck hardware. Doug describes this time as a carpenter’s assistant as “one of his best summers.”

Night Runner was completed in 1980, and her first race was around Vashon Island. This was immediately followed, of course, by the Swiftsure Race in Victoria. I have had the pleasure of sailing and winning Swiftsure twice aboard Night Runner in recent years. I’d like to take the credit, but Doug has 50 Swiftsures under his Sou’wester, so he oughta know the way.

Singlehanded Transpac

Less than one month after her first race, on June 6th, 1980, Doug set sail from San Francisco in pea soup fog. He was bound for Hanalei Bay, Hawaii, in the Singlehanded Transpacific race. He covered over 600 miles the first three days, beam reaching in over 30 knots and heavy seas. By the end of the third day, the autopilot had enough and packed it in. Doug brought his toothbrush on deck and put his sextant where he could reach it as soon as the sun broke through the cloud deck. Sixteen hours was about the limit he could handle at the helm. He continued this way until he had one of those “Eureka!” moments, and packed the autopilot fuse with aluminum foil. He sailed into Hanalei with it still functioning 15 days later.

As a veteran of the cutter-rigged Night Runner’s foredeck, it’s hard for me to believe Doug’s claims of being able to pull off a gybe under spinnaker in less than half an hour. Night Runner still carries her original spinnaker pole from 1980. which is 22-feet long and has winch-driven chain on the butt end for raising it to clear the forestay on a dip-pole gybe. In actuality, Doug would roll out the jib top, douse the spinnaker that is 65-feet on the hoist and 44-feet on the foot, jibe her over, repack and rehoist, then roll up the headsail. Still, how he could accomplish this in half an hour is beyond me.

A Force for Good

In addition to being a force on the water, Doug’s influence in the sailing community off the water has been profound. He was a founding member, and is still a trustee, of The Sailing Foundation—which was developed from the proceeds of the sale of the Americas Cup defender, Intrepid. Intrepid came within one race of being the only three-time America’s Cup defender in history, narrowly losing to Ted Turner’s Courageous in 1977. Doug was the secretary of the Intrepid syndicate, Gerry Driscoll the skipper, and the aforementioned Bill Buchan was tactician. After a contentious negotiation, Bob Fendler (of Olympic pole vaulting fame) became the new owner of Intrepid and The Sailing Foundation was created.

Not long after, Doug responded to an on-the-water tradedy. A fellow sailor, Arnie Bennett, had been lost overboard and his wife was unable to recover him back aboard. In an attempt help others avoid this sorrowful situation, Doug and several other area sailors implemented a series of tests and experiments, many of which were performed on Night Runner. The result was the development of the Lifesling™. The US Coast Guard’s search and rescue professionals saw the merit in it and soon, with Doug’s help, a patented trademark was secured. The first 44 units were sold to the US Naval Academy and the rest is history. Royalties, to this day, are paid to The Sailing Foundation. In 1986, the foundation created the Safety at Sea seminars with these proceeds.

Awards, Achievements, and Accolades Beyond Belief

With Night Runner, Doug’s sailing exploits became a blur of enviable activity. He raced and cruised as prolifically as any boat or skipper in the area. These stories could fill a hundred articles, but he says the sailing accomplishment he’s most proud of is being awarded Blue Water Medal by the Cruising Club of America. This was in 1998 for seamanship on his trip around South America via Cape Horn and Panama Canal on Night Runner. He adds, “They also gave it to the British yachting fleet for the Dunkirk rescue, so I was in good company.”

This high honor, however was only one of Doug’s truly remarkable sailing achievements, which also include:

- 100,000 offshore miles

- Charters in the BVI, Bahamas, Tonga, New Zealand, Grenadines, Scotland, Turkey, Greece

- 13 races to Hawaii: 11 Vic Maui Races, beginning in 1968 (twice setting the elapsed time record in the 70s aboard the Spencer ‘65 Ragtime and Bill Lee’s famous Merlin), 1

- Singlehanded Transpacific (1980), 1 Transpacific (1951)

- Tahiti Race as Navigator on Inisfail (1972)

- 50 Swiftsure Races (1st overall in 1977, 1998, 2011, 2013)

- Four Van Isle 360s (1st Div II 2009)

- Extensive cruising in the Pacific Northwest, including Southeast Alaska cruises in 1950 and 1990

- French Polynesia cruise 1982

The Good Life

These days find Doug comfortably residing in Anacortes, WA, with his lovely and loving wife, Karen. They travel widely. He recently retired 57 years after his original federal appointment, signed by Robert F. Kennedy during the Eisenhower administration, was taken off the office wall. Doug also had a book published—Justice for Ward’s Cove—about his defining legal case, a 27-year saga that culminated in a ruling in his favor from the US Supreme Court.

His grandsons, Will and Daniel, visit often, as well as a plethora of sailors from the Pacific Northwest that have carried on his legacy, some of whom wear lifejackets. He is learning classical guitar and still spends time aloft in the bosun’s chair on Night Runner using the skills he learned building rat lines on the Gracie S.

Doug says sailing gave him his path to adventure and self-confidence. His advice for young sailors? “It’s a lifelong sport, but don’t wait until you are retired for the big adventures. Find a way to get offshore while you are still young.”

Editor

48° North Editors are committed to telling the best stories from the world of Pacific Northwest boating. We live and breathe this stuff, and share your passion for the boat life. Feel free to keep in touch with tips, stories, photos, and feedback at news@48north.com.