#TBT: Paul Bieker… Computers, Carbon Fiber and a Better Solution

1996 Interview by Kurt Hoehne

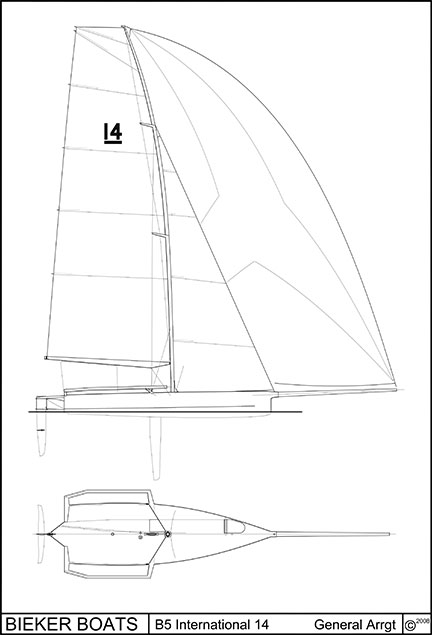

If you see Paul Bieker in the next couple months, you might not recognize him as an up-and-coming force on the worldwide yacht design scene. There may be an epoxy stain on his pants, and his mind may already be on the next project or three. He’ll be up to his elbows in carbon fiber building a series of International 14s to his new design.

If you see Paul Bieker in the next couple months, you might not recognize him as an up-and-coming force on the worldwide yacht design scene. There may be an epoxy stain on his pants, and his mind may already be on the next project or three. He’ll be up to his elbows in carbon fiber building a series of International 14s to his new design.

But he certainly is one of the busiest yacht designers around, forging ahead on his strengths: tremendous computer skills, particularly in analyzing engineering requirements; an intuitive feel for performance sailing, gathered over years of sailing and racing both large and small boats; and a willingness to innovate in both construction and design. His interest in sculpture has given all his designs a modern, angular and attractive look.

The 33-year-old Bieker, exudes a quiet eagerness. As he talks of his designs and ideas, he picks up speed and energy as if he were discovering or creating something right on the spot, and simply wants to share it. The act of sailing is still clearly fun for him, not just part of the job. It’s not easy being a yacht designer these days. Production boats are designed by “in-house designers,” the rare custom racer is designed by the known names like Farr, Nelson, Reichel/Pugh, Frers, Davidson et. al., cruisers generally come from the boards of Perry, Paine, Holland et. al., dinghy design is in a state of transition, which is a nice way of saying there is a very small market.

So how does a talented designer of boundless energy get to be a success? Like most designers, it started with doodles in the margins as a schoolboy in Portland. As a youngster, Bieker sailed in Portland and often raced and cruised on Puget Sound. After Bieker finished high school, his father took the whole family cruising to the South Pacific for 1 1/2 years. When it came time to head toward a career, Bieker studied architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design. “I naturally gravitated toward the fine arts. But that was so subjective, my interest went back to boats,” he explained. Bieker’s next academic stop was the University of California-Berkeley where he studied naval architecture, graduating with high honors.

After graduation, Bieker worked for Gary Mull, but soon found that applying some of the skills gained at school was difficult. He moved back to the Northwest and worked for Guido Perla and Associates, a firm that focuses primarily on commercial vessels. Ironically, this is where Bieker’s own concepts of applying computer design to yacht construction started to form.

Many of the commercial vessels were built of steel. Using computers to lay out the panels, form, function, strength and cost effectiveness could be combined. Together, designer and computer could figure out how to configure steel panels so they were strong and light, and do so without much waste. Ships, after all, can be stronger in some places than other. Computers not only could help design the boat, they could also direct metal cutting machines to do their job with amazing accuracy.

Bieker figured the same degree of engineering could be applied to other mediums such as wood and fiberglass. He already had in interest in the actual shapes that would be fast. Thus started the red boat, a 21-foot, 550 pound dinghy that will plane in little more than a zephyr. Bieker built the boat himself of computer cut plywood panels. To any performance -minded sailor, his boat struck an immediate chord as it zoomed effortlessly.

To International 14 sailors like Jaimie Hanseler, Chris Bundy and Larry Craig, Bieker represented a chance at something different in the ever-evolving 14 design derby. In 1991, Bieker drew and later built his first two I-14s while working part time for Elliott Bay design, another firm focused on commercial vessels. Hanseler and Bundy sailed their I-14 to victory at the U.S. Nationals on San Francisco Bay while Craig and Bieker came in second. This set the stage for Bieker’s promising career. Bieker’s interests lay beyond the I-14s. In designing them, he began to realize the full impact of computer design on construction, and the implications it had for larger vessels. Seeing how under-engineered sailboat construction was, Bieker saw potential for completely new construction techniques. With computers, there was no need to follow methods simply because that’s the way it was always done, or because some wise shipwright said that it was the only way to build a boat. “I want to use pure thought and logic to come up with a better solution,” explains Bieker. “The computer can be used to streamline both design and construction.” He sees his role of designer as integrally involved in construction. The fact that he still builds I-14s himself shows that this is one designer that relishes time out of the ivory tower. Fortune began to smile on Bieker. Local sailor George Thurtle saw a picture of the red boat planing on the cover of a magazine, and decided that a 55′ cruiser of the same pedigree would be exciting. The boat is currently under construction at Shaw Boats in Aberdeen, and is scheduled for a summer launch. Innovation abounds on this boat. One of the more interesting features is a deck box that houses a mast ram and anchors the gooseneck. This arrangement allows mast compression to be quickly eased, and eliminates the prodigious forces of the boom on the mast. Another innovation is a built in shock absorber in the keel to limit damage in case of a grounding.

To International 14 sailors like Jaimie Hanseler, Chris Bundy and Larry Craig, Bieker represented a chance at something different in the ever-evolving 14 design derby. In 1991, Bieker drew and later built his first two I-14s while working part time for Elliott Bay design, another firm focused on commercial vessels. Hanseler and Bundy sailed their I-14 to victory at the U.S. Nationals on San Francisco Bay while Craig and Bieker came in second. This set the stage for Bieker’s promising career. Bieker’s interests lay beyond the I-14s. In designing them, he began to realize the full impact of computer design on construction, and the implications it had for larger vessels. Seeing how under-engineered sailboat construction was, Bieker saw potential for completely new construction techniques. With computers, there was no need to follow methods simply because that’s the way it was always done, or because some wise shipwright said that it was the only way to build a boat. “I want to use pure thought and logic to come up with a better solution,” explains Bieker. “The computer can be used to streamline both design and construction.” He sees his role of designer as integrally involved in construction. The fact that he still builds I-14s himself shows that this is one designer that relishes time out of the ivory tower. Fortune began to smile on Bieker. Local sailor George Thurtle saw a picture of the red boat planing on the cover of a magazine, and decided that a 55′ cruiser of the same pedigree would be exciting. The boat is currently under construction at Shaw Boats in Aberdeen, and is scheduled for a summer launch. Innovation abounds on this boat. One of the more interesting features is a deck box that houses a mast ram and anchors the gooseneck. This arrangement allows mast compression to be quickly eased, and eliminates the prodigious forces of the boom on the mast. Another innovation is a built in shock absorber in the keel to limit damage in case of a grounding.

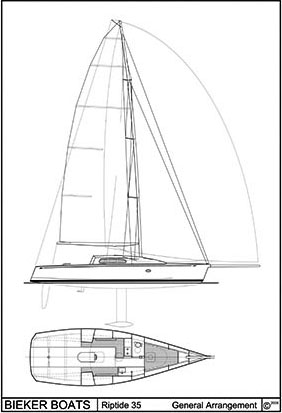

But the coup d’etat thus far in Bieker’s career began about a year ago when Jonathan McKee approached him with an idea for a 35-foot racing boat. “It was kind of a political statement,” Bieker says of the concept. It would be a return to the true racer/cruiser with an inboard and headroom, but be exciting enough for a gold medalist and 18′ skiff sailor to enjoy sailing. Ripple may well be a blueprint of future racer/cruisers, and at the very least it’s alive with ideas that have been lost on today’s production boats.

Ripple is worthy of an article or two all by herself. Bieker and his computer laid out the construction so that surplus honeycomb from Boeing could be used in the flat sides, leaving only the smallest area at and below the waterline for the problematic curves. While Ripple weighs in at only 4,700 pounds, her construction is very strong and progressively more conservative toward critical areas. The keel, for instance, is steel. Swept back spreaders support the mast without a permanent backstay, and running backstays are applied for only the roughest conditions. Rig tension is gained by an in-the-mast purchase system for the forestay. The fractional rig can carry a nearly masthead length genoa in light airs, giving Ripple amazing speed in those conditions. Water ballast lends power in a blow, but a keel bulb provides ample ultimate stability.

Ripple is worthy of an article or two all by herself. Bieker and his computer laid out the construction so that surplus honeycomb from Boeing could be used in the flat sides, leaving only the smallest area at and below the waterline for the problematic curves. While Ripple weighs in at only 4,700 pounds, her construction is very strong and progressively more conservative toward critical areas. The keel, for instance, is steel. Swept back spreaders support the mast without a permanent backstay, and running backstays are applied for only the roughest conditions. Rig tension is gained by an in-the-mast purchase system for the forestay. The fractional rig can carry a nearly masthead length genoa in light airs, giving Ripple amazing speed in those conditions. Water ballast lends power in a blow, but a keel bulb provides ample ultimate stability.

So far, Ripple has shown some amazing bursts of speed, showing her heels to the maxi Cassiopiea in certain conditions. She won the Pulley Point race in March. In the gear-busting Southern Straits race she finished second. In one amazing half hour stretch in 30 knots of wind, the speedo never went below 17 knots! Ask the guys onboard Cassiopiea about the boats around them during that leg, and they’ll talk about the Santa Cruzes and, with a shake of their heads and a sigh, “and that Ripple…” Perhaps more importantly than the speed, during the delivery to Canada, Ripple hit a rock at 7 1/2 knots and there was only minimal damage. What sets Bieker apart? He takes a holistic approach to design, engineering and construction. In many designs, these fall to different people or even different departments. The designer creates a shape and layout, the engineer makes it work on paper, then the builder makes it work in real life. Along the way things can change dramatically. Bieker and his computer tackle the first two tasks simultaneously, gearing the process with the builder in mind and sometimes doing the construction himself. One might alter that old cliche and say he’s “starting with a blank screen.” Another essential difference is that, so far, his creativity is unfettered by the constraints of production runs and measurement systems. It’s a fresh approach, and combined with his background in commercial design and the freedom of the I-14 rule, is resulting in some true innovation. The common denominator between his boats appears to be raw speed. Sailboat design is all over the board trying to find it’s next incarnation. Bieker represents a departure, new ideas backed up by computers and not history. It’s significant because he’s one of the few designers in this country that have broken through and are actually succeeding at it.

Paul credits the Seattle I-14 fleet for much of his success. “I couldn’t have designed the 35 and 55 without the I-14 fleet.”Not only did fleet members give him the opportunity to design boats, they even gave him a round trip plane ticket to go to Australia to learn about I-14s there. With recent changes to the design parameters, including more sail area, the I-14s will remain a challenge for designers and sailors for years to come.

By his own admission, Bieker has some things to learn. He “tends to mull things over too much,” spending inordinate time on some details. Then there’s the experience factor. While his fresh approach can result in innovation, the 55-footer, for instance, is running over budget, in part because of misunderstandings that, with more experience, he may have avoided.

Bieker, who has opened his own design office called Riptide Design, has a busy present and future. For starters, he and his wife Charlene are expecting their first child. On the design and construction side, he will be building more I-14s to his new design and overseeing completion of the 55-footer. Some interest has been expressed in sisterships to Ripple – interestingly from East Coast sailors. Currently spread around his office and his computer are stress analyses on braces for transporting prefabricated houses to Native Americans in Alaska by ship. He recently completed an engineering study on a Todd Shipyard dry-dock due for expansion.

These projects seem appropriate. Bieker, has found a way to integrate modern CAD-CAM techniques, commercial demands, modern materials and intuitive design. Experiences outside the sometime parochial world of sailboat design have helped him carve a niche where innovation is the exception and not the rule.

Kurt Hoehne is a Northwest sailor and author. He is currently producing his own Northwest sailing website “Salish.com.”

Joe Cline

Joe Cline has been the Managing Editor of 48° North since 2014. From his career to his volunteer leadership in the marine industry, from racing sailboats large and small to his discovery of Pacific Northwest cruising —Joe is as sail-smitten as they come. Joe and his wife, Kaylin, welcomed a baby girl to their family in December 2021, and he is enjoying fatherhood while still finding time to sail, make music, and tip back a tasty IPA every now and again.