How I Learned to Enjoy the Sailing Portion of the Cruising Lifestyle I Love

Mother’s Day 2023 was a windy one. Ask me how I know.

The sail back home from Gig Harbor to Tacoma was supposed to be a celebratory affair, an exciting end to our weekend getaway on our Hunter Legend 43, Muse, and a perfect way to spend the holiday. What it turned into, however, was the catalyst for me to get serious about my sailing anxiety. The northerly winds whipped through Colvos Passage on the west side of Vashon Island, climbing to 23 knots, and my fear took complete control over me. Sustained winds of that strength usually result in a small craft advisory, but it certainly didn’t help matters that I lost my mind.

Cruisers are often warned against sticking to a set schedule, and for very good reason. Mother Nature calls the shots. But sometimes the pressures of life push us to venture out of safe harbors when it would be better to stay put. I believe this is especially true for us weekend boaters who squeeze our adventures in between a whole pile of responsibilities on land that, frankly, don’t give a crap if the sailing conditions for our return trip are beyond our levels of comfort and experience. As much as we would like to have the freedom and flexibility to extend our trips, there are bills to be paid, classes to attend, corporate overlords to appease, and the list goes on.

Many times, the enjoyment of being in a beautiful anchorage with my husband and family has been completely overshadowed because Sunday’s forecast was a big, looming monster waiting to devour me on the way back home.

Some of this fear is practical and serves me well. It’s true that sailors should know their limits and be weather-wise. The problem was that my limits were far more limited than other sailors I know. I have always been very risk averse, but with my slow and steady approach, I can usually overcome my fear enough to reach my goals—working up the courage to rollerblade down the steep driveway like all the other neighborhood kids; facing my fear of skiing year after year to get to a nice, comfy intermediate level; persevering through stage fright as I gently built up my skills in performing and public speaking.

I’ve always been able to reach my desired level of proficiency, despite my fears. But sailing was somehow different. After living aboard for several years, and taking the boat out regularly during the warm season, my skills and confidence seemed to be stalled. Not only that, the anxiety had become truly debilitating.

During that Mother’s Day blow, we were on a close reach and the southern tip of Vashon was drawing nearer and nearer. We made a plan to ease the sheets, skim past the bottom of the island, and keep heading toward Commencement Bay on a beam reach. The wind had other ideas, however. The beautiful mess of glacier-carved land and water that is the Salish Sea tends to do funny things, and it was an unwelcome—but not completely unexpected—surprise when the wind suddenly changed direction and built to the point that we were overcanvased and very uncomfortable. Perceiving that I was completely out of my depth and that death must surely be imminent, I became totally petrified at the helm.

I was absolutely useless. No, less than useless. I ended up yelling at my husband, Andrew, who was just trying to help me get a grip in the most gentle way he could. He had to navigate the situation singlehanded, and it took me a full 20 minutes to regulate my nervous system to the point where I could stop shaking.

Quickly adjusting our heading and trim, and reducing sail meant we were much more comfortable for the remainder of the trip. Physically comfortable, anyway. Inside, I was a mess of guilt and shame. Could I even call myself a sailor if I was that afraid of sailing? I felt like such an embarrassment and a failure.

The sailing season was just getting started, and I realized that I had a choice. I could be absolutely miserable, dreading any winds above 15 knots for the next several months, not to mention in the years to come, or I could do the hard work of addressing the issue and changing my brain so I could reach my goal of becoming a more confident, capable sailor.

Before going further, let me say that I am not a therapist, and if any readers are struggling with mental wellness, they should definitely consult a professional. I am very excited about the massive transformation I’ve experienced, though, and I hope my story gives anyone else with sailing anxiety some hope for their own wellness journey.

Fear is a very hard thing to talk yourself out of because it doesn’t come from the part of the brain primarily responsible for higher level reasoning, the cerebral cortex. The fight/flight/freeze instinct is exactly that, an instinct, and we share it with all other creatures that have a central nervous system. This instinct evolved long before our cerebral cortex gave us many executive functions, so it makes sense that often our fear response is not reasonable. I could understand this at a cognitive level, but that didn’t make my panic feel any less real.

I’m a life coach, so I already had an idea of where to begin, but I often find it helpful to reach out to my network of colleagues and process things with their support. After this incident, I was very motivated to put that resource to use. One lovely and skilled coach I worked with helped me to listen to my fear to find out what it was trying to tell me. What was the root belief that was driving the behavior?

As it turns out, the scariest part of sailing for me is when I feel like I’m out of options. I believe the boat is completely out of control and all hope is gone. I told you it might not be reasonable!

But I knew that invalidating those fear-driven thoughts would not make them go away and my coach knew it too. It would be nice if we could simply stop believing unreasonable things, but that’s often easier said than done. Since anxiety is a tricky beast that runs on instinct, it could care less about my intentions to simply stop thinking that way.

What I learned about my fear is that it’s like a scared animal. I couldn’t reason with it. I had to accept it exactly where it was and honor it for trying to keep me safe.

But what about my goal of becoming a more confident sailor? I wasn’t willing to call it quits and walk away from this lifestyle I love, so I felt that the best option for me would be to gradually and gently change my understanding of what it means to be safe.

I had heard of exposure therapy before, but I had lots of previous sailing exposure and my experiences year after year weren’t getting any better. That’s when I learned about the gradual exposure technique.

In gradual exposure therapy, you gently move the target forward until you reach your goal, which is to eliminate the anxiety as much as possible. But to do that, you have to accept your fear exactly where it’s at without shaming it or trying to ignore it. Board-certified clinical psychologist, adjunct Professor at the Yale School of Medicine, and past president of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Dr. David Tolin, is a big advocate for this type of gradual exposure therapy. Dr. Tolin has seen huge success in the treatment of all kinds of anxiety disorders. He’s written over 200 peer-reviewed articles on his findings, but he also has a book called Face Your Fears for everyday psychology enthusiasts and anxiety sufferers like me.

Since fear can be like a scared animal, a related example can help illustrate how gradual exposure therapy works. If I had a dog that was terrified of boat rides but it was really important for me to get to a place where I could bring it along on weekend cruises, I probably wouldn’t just jump right in and expect the dog to get a grip. That would most likely result in many miserable weekends aboard and perhaps even a dog that became more and more anxious over time.

Instead, I would take the dog for a walk down at the marina. As we moved along the dock approaching the boat, I would pay attention to any signs of anxiety that arose. If the dog got visibly uncomfortable as I tried to coax it on board, I would stop right there at the dog’s threshold of fear. Then I would take the semi-scared pup back up to the car before the melt-down phase, comforting it until it was calm.

There. We met our edge, we backed away, and nothing bad happened. See? Everything is okay.

The next time, I would try to get the dog aboard and just have a nice picnic in the cockpit while tied to the dock. The time after that I might start the engine, but as soon as the dog was showing signs of anxiety, I would stop and back away from the threshold. Gradually that fear threshold would be extended. It might take a long time, but eventually the dog would be able to enjoy short boat rides and then full weekend cruises.

Getting very clear on my fear threshold with sailing was a top priority in my healing work. When I was really honest with myself, this moving target became evident. For me, taking the helm in moments when the wind is building past 15 knots and needing to make quick decisions about managing the boat and sails felt too close to that threshold. The key was noticing how my body responded in these types of situations.

That’s when I started incorporating mindfulness into this exposure work—noticing my rise in adrenaline and reassuring myself that I am safe—based on the anxiety therapy practices of Dr. Claire Weekes, who taught her patients that although the fear might be real, the danger usually is not. Those who struggle with anxiety disorders, she believed, had overly sensitive nervous systems. According to her theory, the key is to notice how your body responds without being afraid of the response.

Could I feel the wind building, watch the inclinometer inch toward 15° or 20° of heel, and sit calmly with the stress hormones flooding my body? It was one thing to know my threshold. But it was quite another to meet it and simply welcome the physiological response.

I was desperate to keep moving my fear threshold forward and make the cruising lifestyle work for me and my family. So, I went forward with the rest of the sailing season, this time equipped with a plan centered around gradual exposure therapy and Dr. Weekes’s anxiety management principles, and refined with help from my coach. These practices were effective at helping move my fear threshold and made an unbelievable difference in my sailing anxiety in just one season.

I made the following rules for myself:

- Notice how my body is feeling. Am I calm? Or do I have adrenaline rushing through me? Am I meeting my threshold?

- If I’m getting close to the edge of my fear, ask my husband to take the helm. I feel safer managing running rigging when I’m scared, so that’s what I planned to do.

- Take deep breaths. Notice that I’m safe and nothing bad is actually happening.

- If I’m still at my threshold, threatening to cross over into panic, do whatever I need to do to help the boat avoid any actual catastrophes, then let my husband know I need a few minutes below deck to get calm.

- Again, take deep breaths, and notice that I’m safe. When the fear subsides, move back up into the cockpit.

Does it make sense to leave the helm or go down below if conditions are sketchy? Not necessarily, but it’s better than having a panic attack. And the truth is, there’s rarely ever an actual emergency. I just have to get my anxious brain to understand that, and finding a way to gradually, mindfully expose myself to sporty sailing is working. It really is.

Fast forward to the end of summer. We took a two-week cruise through Puget Sound, hitting seven different destinations from Poulsbo to Penrose, sailing almost the entire way. I had been practicing my gradual exposure plan since spring and, although I still felt a rush of adrenaline with every gust, whenever the wind caught the opposite side of the boat after a tack, or when the boat would lean into that first heel after raising the mainsail, I would take notice of how my body responded. The adrenaline would wash over me, I would take some deep slow breaths, and I would know that I’m safe.

And once I felt safe, you’ll never believe what happened next. I actually felt a rush of excitement!

Okay, maybe you can believe it, but I couldn’t. My goal was to just feel okay with sailing, so it came as a delightful surprise that I actually felt great.

Toward the end of our trip when the wind was climbing toward 20 knots through Balch Passage and our reefing system was on the fritz, I didn’t panic. My husband and I calmly made any adjustments we could and changed our plans to head to a more protected spot. No freezing up. No shaking. In fact, I didn’t feel scared at all. Afterward, when I made the call to drop the sails and motor the rest of the way into Filucy Bay, I felt no shame. I just knew I wasn’t ready for 20+ knots of wind under the full power of Muse’s mainsail.

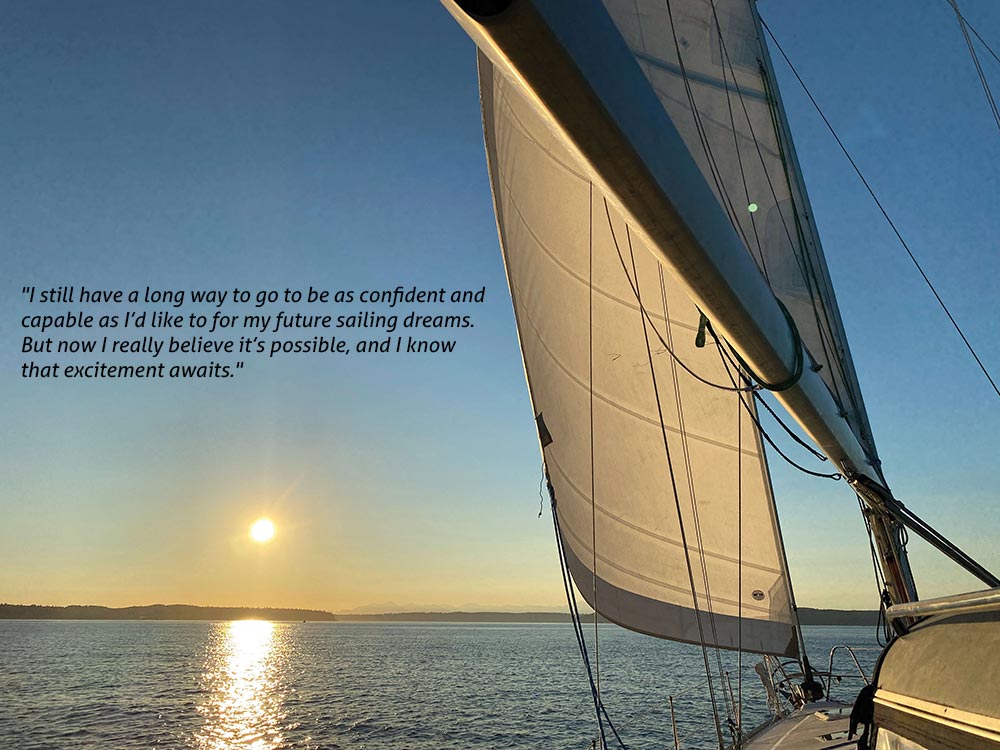

I still have a long way to go to be as confident and capable as I’d like to for my future sailing dreams. But now I really believe it’s possible, and I know that excitement awaits.

I still have a long way to go to be as confident and capable as I’d like to for my future sailing dreams. But now I really believe it’s possible, and I know that excitement awaits.

Samantha McLenachen and her husband, Andrew, live aboard with their children in Tacoma, Washington. They proudly own the newly opened marine repair business, Independent Marine Service.

Samantha McLenachen

Samantha McLenachen and her husband, Andrew, live aboard with their children in Tacoma, Washington. They proudly own the newly opened marine repair business, Independent Marine Service.