Last month, we were introduced to Peter and Ginger Niemann — award-winning Seattle-based circumnavigators whose journey home through the pandemic-closed world found them boat-bound for more than 300 days. They were in Turkey when Covid lockdowns began. This is the first of a three-part series sharing the story of their epic voyage home to the PNW.

The following article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of 48° North.

The sun had just set. Our ketch Irene was sailing gently in a beautiful scene, with the sky lit by a soft pink glow. We were surrounded by towering clouds. The entire crew of Irene, both of us, were in the cockpit enjoying a quiet time together.

The main had a reef tied, despite light wind, because the day had been filled with drama — we had been hit by thunderstorm after thunderstorm — and we had learned to simply leave it reefed all the time. It was quick work to drop the mizzen and roll up the jib, but tying a reef took time. And those thunderstorms struck quickly! One minute we would be sailing gently and upright in light breeze and sunshine, the next minute Irene would be rail down in pelting rain and surrounded by lightning strikes. The thunder was deafening as we scrambled on the slanted deck to reduce sail. But all that drama was in the past, as we enjoyed our now-tranquil scene. Suddenly, our relaxed mood was shattered. BEEP, BEEP, BEEP, BEEP…. The chartplotter screen read, “NO AUTOPILOT.” No rest for the wicked, as they say.

Rebooting brought the pilot back on line, at first for an hour, then ten minutes, finally just for a few minutes. Eventually it quit completely. We were worried, because we were approaching the famous Malacca Strait, with Sumatra to starboard. What is Malacca Strait famous for? Thunderstorms, commercial shipping and fishing boat traffic… and pirates. Pirates were not a worry, research showed that the region had no incidents in recent years. But dealing with traffic and thunderstorms was much easier with AIS and radar overlay, and the pilot itself of course is essential equipment. Now all those capabilities were nonfunctional.

We altered course to bring Irene close to shore, where we might find some calm water to diagnose further. We spent two days coasting along Sumatra in the Banda Aceh region, formerly known as pirate central. Groups of sporty little fishing boats came and went in groups, cheerfully buzzing by and occasionally asking for smokes, but never harassing us. We weren’t able to get the autopilot working. We were resigned to the fact that, except during periods of enough steady wind to sail with the windvane, we would be hand-steering with the tiller on the aft deck fully exposed to sun and rain. This, in some of the most crowded waters in the world, and we had over 600 nautical miles to go before reaching Batam Island — our first chance to obtain replacement parts.

Every afternoon, the clouds gathered and the electrical storms pounced on us. The rain was welcome because our water tanks were almost empty, last filled in Egypt, and the passage across the Indian Ocean had been completely rainless. We were on a long odyssey home in a time of pandemic, when a voyaging boat was not welcome in large parts of the world. Normal rest and reprovision was not possible, and we were running low on essentials — food and fuel, in addition to fresh water. On the bright side, each thunderstorm brought us more water, and we were grateful for that.

We had been in Turkey when Covid lockdowns were first put in place. Ginger and I struggled to make sense of the rapidly changing scene and formulate an action plan. We felt that we needed to get back to the Pacific Northwest.

We didn’t want to stay aboard in Turkey because of the very strict confinement policies and political tensions in the region. We did not want to leave our boat and fly back to the States, as many sailors did at the time, because Irene is our only home and it was uncertain when or if we would be allowed back into the country to our boat if we left.

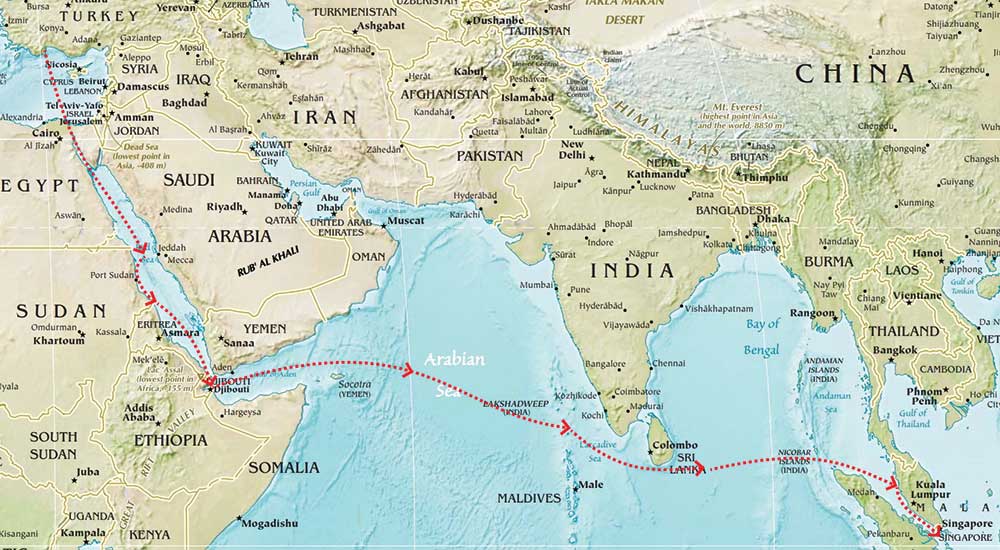

We investigated the possibility of sailing home directly, and noted that the mileage to Seattle was roughly the same heading west via the Panama Canal or heading east via the Suez Canal. However, the Suez was nearby and open, where the Panama was months away and had already been closed for a time. Thus, we judged the eastbound route less likely to be barred (by a closed canal) to us. Suez was only a couple of days away from us and Indonesia was open to arriving yachts when this plan became action. And we could always sail in the open ocean no matter what the state of the borders were. The east route would take us to Japan, where we’ve always wanted to cruise, and the Aleutians, where we were eager to return. Also, the eastward route included much territory we had never sailed before and that we were interested in seeing, assuming (hopefully) that countries would open borders as we progressed. Of course, as it turned out, they did not.

We went to work on our eastbound plan. We found a marina willing to sponsor us for rest and reprovision in Indonesia, and forwarded the necessary documents to them to prepare customs and immigration for our arrival. Things were taking shape — the monsoons and prevailing winds matched nicely as we would move from region to region, as long as we waited for a few months in Indonesia. An added bonus would be ticking off a circumnavigation, our second one.

A minor issue was that our leg down the Red Sea, the hottest sea in the world, would be at the hottest time of year. Unusual, but doable, we figured. Another unusual aspect would be entering the Indian Ocean at the height of the southwest monsoon with its notorious winds and waves, a time yachts avoid. Also doable, we thought. After all, the ancient dhows historically sailed in this monsoon to India yearly, and they were sewn together with nothing more than coconut rope.

By now, the Turkish regulations allowed Ginger to go grocery shopping, though I was still by law confined to the marina, and we reprovisioned. Luckily, we had repainted Irene’s bottom just before the lockdowns began, and we filled the water tanks and departed for Egypt and the Suez canal, our first steps home. We had spent the last two-and-a-half years sailing away from home, and it was a magical feeling to be homeward bound.

We sailed as planned. The Suez canal was pretty much as expected, hot as Hades and complicated by a culture of “baksheesh” (a small sum of money given as a tip, bribe, or charitable donation). The scenery was interesting enough but we were still glad to leave Egypt behind and enter the Red Sea, which was amazingly beautiful. The heat and dust were merciless. We suffered from heat rash but sailed onward. We had not realized before how much interesting bird life was in this sea. Seabirds crowded the rigging and swallows landed on deck and flew freely through the cabin. They were unafraid and would perch on our fingers. At night we were plagued by thunderstorms, but we just reefed down and carried on.

A meteorological phenomenon called a Haboob engulfed us as we sailed along the Sudanese coast. Thick dust reduced visibility and the wind direction swung around against us. We took shelter by anchoring in a marsa (the Arabic word for an anchorage or dockyard) to wait it out, but we were noticed and soon boarded by the Navy. The officers were not at all sure why we were there, and searched the boat. After hours of uncomfortable interrogation, we were finally given permission to stay for what was left of the night and depart in the morning. The Haboob was still blowing that morning, and all day we motored through an inside small boat channel, narrow and twisting and bordered by dangerous coral, returning to the Red Sea proper that night. It was a relief to be sailing in more open waters again.

We anchored in Djibouti to get water and refuel, but were denied permission to go ashore. It was a taste of things to come. Our scallywag agent, Moustique, brought containers of diesel and some motley vegetables out to Irene at anchor for a premium price. Thunderstorms blew fiercely at night.

The wind was strong as we sailed into the Indian Ocean, as expected. We didn’t worry about pirates because their skiffs could not operate in the rough conditions. We sailed with just a tiny reefed staysail set, and the motion aboard was violent. We would normally heave-to in these conditions, but we needed to keep moving this time. There was no point in lingering, as this wind was forecast to blow like this for weeks in the same direction and at the same strength. Cooking was impossible — we ate crackers and drank water while we hung on. As we sailed past Socotra at the entrance of the Indian Ocean, a nearby container ship told us the wind was blowing 59 knots steady, gusting to 64. The waves were gigantic, but not dangerously steep. Every now and then, a breaking wave top would find Irene and her decks would disappear in foam. When those occasional wave tops hit us, down below it sounded like a collision with a garbage truck.

After a week and some fast miles, the wind eased up (as it always does) and we sailed across the Indian Ocean past the Maldives, India, and Sri Lanka. As we passed close by land, our phones connected and we read the latest world news. Among the news we learned that a bulk carrier had run aground on a reef at Mauritius, likely because the bridge crew was distracted by their cell phones as they connected to get news, just as we were doing. A fishing boat motored close by and kindly tossed us some fresh fruit in exchange for Turkish Doritos.

Irene sailed onward, in light wind now, and approached the Malacca Straits, where a minor disaster (lightning?) struck and we found ourselves hand-steering for days. We crossed the Straits to the Malaysian side in the hopes of obtaining permission to stop at Pangkor Marina for emergency repairs. We hailed James, the manager, at the marina and he informed us that he was unable to help unless we declared a mayday — and even then it was unclear if the Navy would allow assistance to a foreign vessel on the move — so we continued on.

We developed techniques for coping. Covering up for protection from the brutal sun was essential. Irene pulls slightly to starboard as she motors, so we rigged a line to a winch to take that static load off the tiller. While steering, we sang songs, ate snacks, drank water, and hoped for wind. When the wind blew, life was wonderful. We would quickly rig the wind vane, and go about life below decks, popping our heads up every 15 minutes to check for traffic. The water became shallower, and we were able to drop the anchor, right out in the open strait, if we were lucky to encounter a calm in a good place. The electrical storms continued, but were less violent and less frequent.

When we finally arrived at Batam Island in Indonesia, we were exhausted, suffering from heat rash, and badly needed a rest. We were almost out of food and water, and were low on diesel. We had hand-steered many of the last 700 miles in some of the most crowded and thunderstorm beset waters in the world, and we were short on sleep. We were about to be tested further, though.

We arrived to be greeted by a small army of health and immigration officials and to hear the news that rules had changed, and we must leave immediately. Yellow police scene tape was stretched across the dock to emphasize the point. Ginger and I looked at each other and shrugged. We were resigned, there wasn’t anything we could do about the situation. Government decrees and immigration policies are all powerful like waves and weather, something we must adapt to.

We can’t say that this was the lowest point of our years of sailing, but it certainly ranks prominently in the list. Our marina negotiated time enough for us to work on the autopilot and two fantastic marina employees volunteered to shop for provisions for us — returning after dark the night before our departure.

Ginger got on the computer to search for a country that would accept us for a time. Only Japan was open to us, and it was too early to arrive. If we arrived in Japan too early, our three-month visa would expire before weather in the North Pacific would be appropriate for crossing to the Aleutian Islands. Ginger found that Singapore would allow us to stay, but without visas — we were not ever to go ashore. It was our only option. So we sailed the short hop of about 20 nautical miles across the Singapore Strait to Changi Sailing Club and picked up a mooring for a long stay. We would stay on that mooring for five months.

We were well on our way home to the Pacific Northwest, but the Covid-closed world was certainly making it interesting. Even under less than ideal circumstances, our appreciation for our boat, the cruising lifestyle, and one another was never in doubt.

Originally from Seattle, Peter and Ginger Niemann now call Port Townsend home after two circumnavigations. They were awarded the Cruising Club of America’s Blue Water Medal in 2022.