Since buying our 1984 Grand Soleil 39, Yahtzee, in Seattle in 2012, our family has cruised over 15,000 miles from Washington, Oregon, British Columbia and Alaska, south through Mexico, Central and South America, and now in the Caribbean Sea. Through all those years, miles, and places, our crew has repeatedly learned how to roll with what gets thrown at us — good, bad, or indifferent.

The moments we’ve shared together, the beautiful places we’ve been, and the wonderful people we’ve met have made it all so worth it; but we’ve also seen our fair share of close calls, breakdowns, nasty weather, wet bunks, and frustrating currents along the way. Whether you’re cruising a few miles from your homeport or thousands, mishaps and misadventures shape us as sailors. Some of these are in our control and others are not — it’s how we handle those situations that makes a difference.

For me, there’s no avoiding the sound of my pounding heartbeat in my ear drums when I first realize there’s a problem and the adrenaline starts pumping. Instantly on alert, I’ve learned to balance the need for fast action with the knowledge that slowing down to take a breath, assess, and talk through a situation with my family leads to the best outcome.

We are fortunate to have extensive experience and a deep knowledge of our boat. Still, a hair-raising near miss can shake your confidence and your trust in your equipment. Our path out of the tough moments and back on course, figuratively and literally, is aided by identifying what we can change and control, and what things we cannot. Learning and going as far as we can to be as ready and responsible as we can is key to our happiness as full-time family cruisers, but so is being willing and able to let go of what’s out of our hands and adapt flexibly with what the sea sends our way.

While the following stories are very different in premise and setting, they remain heart pounding, adrenaline producing incidents that I look back on as experiences that taught me about what we can and cannot control while sailing.

A CLOSE ENCOUNTER

It was our second of three weeks in stunning Barkley Sound on the southwest side of Vancouver Island, and we’d worked ourselves into an enjoyable pattern of anchorage finding. The Sound — and the Broken Group in particular — is teeming with excellent anchorages, many of which you can tuck into by yourself, or with only one or two other boats. The habit we’d settled into was to find small, one-boat nooks where we could drop the primary bow anchor, back down, and then set a stern tie to a rock or tree. From these hidey-holes, we’d put the SUP and kayak in the water to explore sand, shell, and driftwood covered beaches until our hearts were content.

while oysters cook on the grill.

Throughout this time, and without realizing it, I’d become somewhat complacent with my typically fastidious piloting. I was about to be humbled… big time. On Yahtzee, we have an older Raymarine C90 chartplotter down below at the nav desk that is mostly used for monitoring the AIS and radar. Our primary navigation tool is an iPad at the helm on which we run the app Navionics. Up to this point, the Navionics charts had been accurate throughout the Salish Sea and I hadn’t noticed any major inconsistencies between them and what we were actually seeing with our eyes or on the depth sounder — hence, my trust.

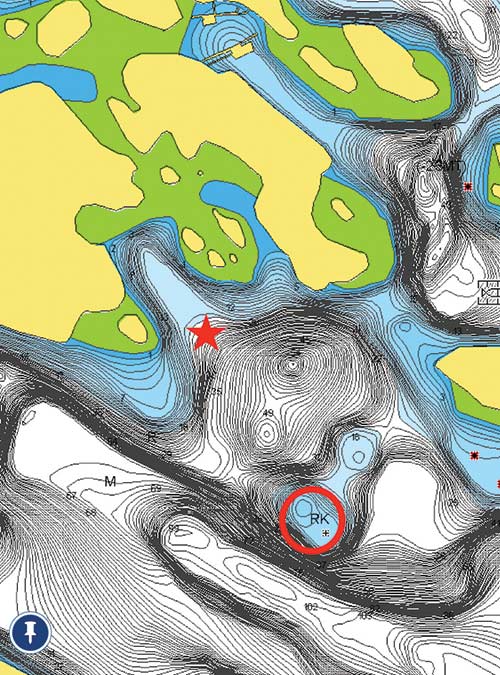

Following our routine, we sailed a short hop into the northern reaches of the Broken Group, doused the sails, and turned on the engine. Passing by a set of low slung islands with no names on the chart, we spotted a sweet little pocket cove to complete our stern set. About a tenth of a mile out from the cove, the chart showed a spot that was no shallower than about 10 feet at mean lower low water. With Yahtzee’s 6.5 foot draft, I wasn’t worried about it, but I made a mental note of its presence so we wouldn’t pass directly over it. On our way into the cove, we left this shallow spot to starboard, backed down, and set our anchor and stern line. It was a warm day and, as afternoon gave way to evening, we grilled oysters on the stern and then turned in early.

The next morning, after a paddle around some nearby islands, we decided to weigh anchor and look for another cove. Jill was down below tidying up after breakfast and getting the boys ready while I reeled in the stern line and raised the anchor. With the anchor up, I went back to the cockpit, engaged the engine in forward idle, checked the chart, and set Yahtzee on course with the autopilot.

Realizing that I hadn’t done the last step of locking the anchor into the bow roller, I walked forward down the starboard deck, and that’s when I saw it. A massive rock the size of a car sat just below the surface of the water, and slid by just feet from the hull. Instantly, my heart thumped and I ran back to the cockpit and put the engine in neutral to assess our location. As our speed slowed, I looked at the chart again on Navionics. It showed that we were near the shallow spot, but definitely not right on top of it. I zoomed in, no rock.

Fortunately, we’d missed this hidden behemoth that could have done serious damage to our boat and possibly our crew. To this day, that moment still haunts me.

Afterward, I felt like I’d trusted the chart too much, and should have given the shallow spot a wider berth — that was on me. Increasing my vigilance is something I can control, an uncharted rock I cannot. From then on, I began regularly double and triple checking the charts when needed, and will even look at overhead images on Google Maps of channels, shallow areas, and reefs. I’ve also been a lot more careful about giving ample room to even minuscule features on a chart if I think something is amiss.

anchoring spot (starred) in Barkley Sound.

One great thing about charts is that they are constantly improving and crowdsourcing is making them even better. Our incredible near miss in Barkley Sound was in 2016 and, in 2019 while thinking back on it, I checked the spot on Navionics again. Lo and behold, there was a significant update to the chart and the shallow area now showed more detail and the rock is thankfully charted in what seems to be the proper position.

SAIL THE BOAT

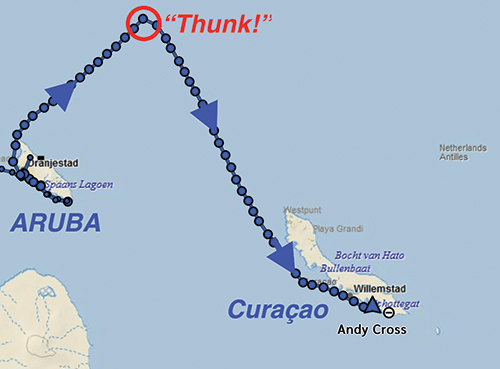

Seven years and many miles after the close call with the Barkley Sound rock, we departed Oranjestad, Aruba for a projected destination of Ponce, Puerto Rico, nearly 400 miles to the northeast. If we could make it farther east, we would, and if we needed a closer destination, Curaçao or Bonaire were both good options. Experience has taught us that once you’re at sea, you never really know.

Sailing northeast from the top of Aruba out into the deep blue Caribbean Sea, our hopes were high. But right away, things were slightly amiss. The wind was stronger than projected and coming more out of the east, instead of the south like we thought it would be. The overall conditions, though, weren’t so bad that we needed to turn around. Instead, we fired up the engine and made as much easting as we could.

Soon, while motoring along under bright sunshine some 40 miles northeast of Aruba, the engine abruptly shutoff with a loud, “THUNK!”

“Not good,” was the thought that whizzed through my suddenly adrenaline-loaded brain. I’m no professional mechanic, but I knew right away this wasn’t a fuel issue and the engine’s vitals were fine — oil, coolant, raw water, battery level. Something else was wrong.

With well over 300 miles to go to Puerto Rico, it was no longer an option for a number of reasons — with no engine, we would have to seriously conserve our battery power and if the weather got worse, there would be no good place to bail out and duck for cover. We needed to figure out the engine problem.

At this point, the state of our engine was out of our hands, but making the most of our next move was still up to us. We could have turned back to Aruba, but the northern tip of Curaçao was only 55 miles away and we trusted our boat and ourselves to get there safely. Cruising attitude is what transforms an unexpected detour into an awesome opportunity, and we get to determine a lot of that. A turn to the southeast had us heading straight for it with a plan to sail through the night and arrive in the early morning, find an anchorage, and assess the engine.

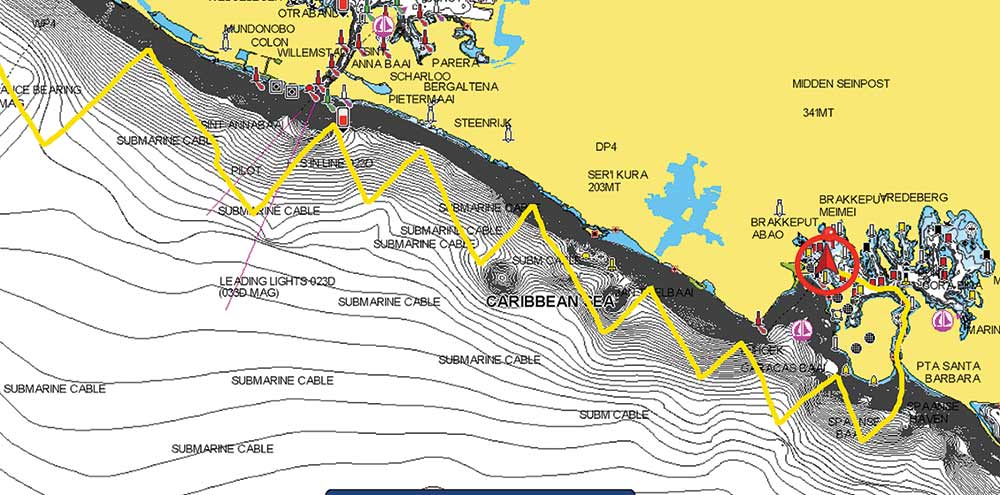

Sailing close-hauled, we neared the western coast of Curaçao in the dark and, when sunrise came, so did a big increase in the breeze. Right on the nose. With no engine to help us fight the wind and seas, we did what Yahtzee does best — we sailed. Short-tacking down the coast in 20-25 knots, it took hours to get to the channel that leads into a very protected bay called Spaanse Waters (Spanish Waters). The tricky bit now was that the entrance channel was narrow and, once inside, we’d need to anchor under sail.

Upon arrival, we were confronted with an array of things outside our sphere of influence. The conditions were manageable but not ideal, the narrow channel left little margin for error with reefs on either side, anchoring options elsewhere weren’t promising, and of course we didn’t have power if we got into a jam. It was a nerve-racking scenario. We had to trust ourselves and give it a try, though; plus, we knew we could turn back out to sea if needed.

My heart rate ticked up as we talked through the plan as a family. Everyone had a job and a clear understanding, and I took a deep breath. Soon, we sailed Yahtzee into the channel, passing onlookers at the posh Sandals Beach Resort, and wove our way safely into the bay.

Once inside, we had cleared the most worrisome hurdle, but still had to anchor under sail. We could clearly make out the various anchorages around this incredibly protected body of water, which was almost like a lake. We headed for a section of the anchorage that seemed ideal and was close to a dinghy dock. With Jill and Magnus at the bow ready to drop the anchor and Porter at the main halyard ready to dump the sail, I rolled up the headsail and then turned into the wind. Yahtzee slowed to a stop, the mainsail fell on cue, the anchor dropped and dug into the sand, and we’d made it. Phew!

With Yahtzee settled and the hot Caribbean sunshine beating on deck, we set about cleaning up and drying out the boat, and then looking into the engine. After several days and lots of back-and-forth with knowledgeable friends, we still couldn’t get it running. Stumped, we finally opted to find a mechanic. The prognosis? The bearing between the engine and sail drive (transmission) had failed. The fix? We’ve ordered the replacement parts and the repair is underway.

We couldn’t make the parts come any faster, so we had one more unexpected situation to make the best of. This all happened just as hurricane season was kicking up in the Caribbean Basin. As we learned so well cruising the Pacific Northwest — if you have a destination, it’s best not to have a rigid timeline; and if you have time restrictions, it’s best not to be married to your destination. We let go of Puerto Rico, and made Curaçao Yahtzee’s hurricane hideout for the 2023 season.

Though very different from missing the rock in Barkley Sound, this situation was another reminder that cruising is full of factors outside our control, yet we responded in a way I’m proud of. We talked through an issue, made a plan, and sailed the boat, trusting it and ourselves in the process and controlling what we could — this is what seamanship is all about. With each close call we navigate and learn from, we know a little bit more about the risks involved in our cruising lives, and a lot more about what we’re capable of.

Andy Cross is the editor of 48° North. After years cruising the Pacific Northwest and Alaska with his family aboard their Grand Soleil 39, Yahtzee, they sailed south and are currently in the Caribbean Sea. You can follow their adventures at SailingYahtzee.com.

Andy Cross

Andy Cross is the editor of 48° North. After years cruising the Pacific Northwest and Alaska with his family aboard their Grand Soleil 39, Yahtzee, they sailed south and are currently in the Caribbean Sea. You can follow their adventures at SailingYahtzee.com.