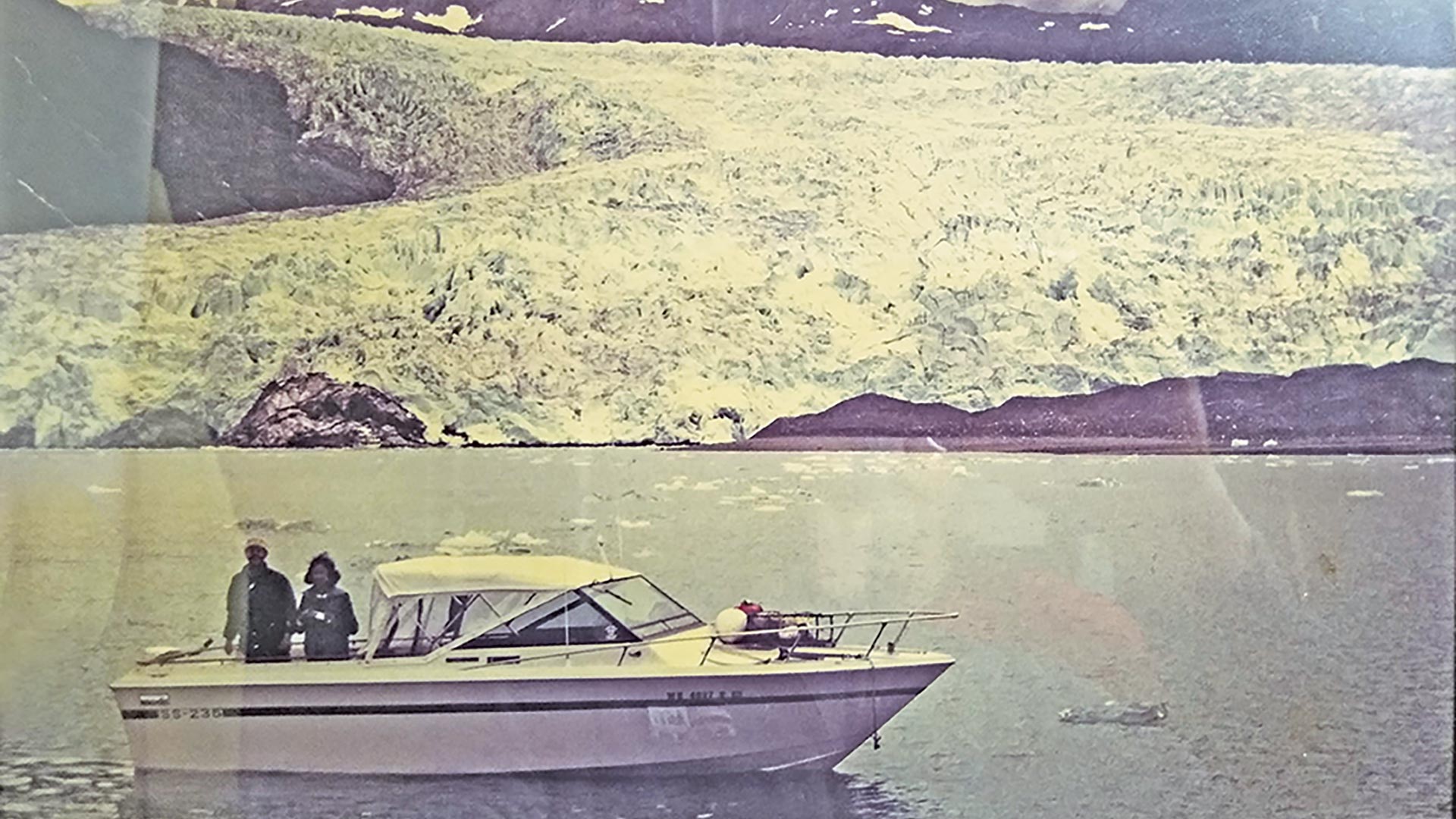

Last summer I was helping my friends Chuck and Charlotte with some garden pruning and when we went in for lunch, I saw an old framed black and white photo of them standing in their Slickcraft 23 open boat in front of a glacier, so I had to ask. They both lit up and told me stories about their two trips to Alaska from Tacoma in that boat in 1977 and 1979, a month each time, and how our boat Sea Lab would be such a great vessel to do that same trip. Chuck and Charlotte had begun their water career in that Slickcraft and subsequently had a long cruising career in their 35-foot Hallberg-Rassy named Queen Charlotte.

Of course, this got Tekla and I thinking… is that possible for us to do?

We have thought about trailering into Canada to see how far we could get but why not leave from home on the C-Dory and go all the way up? There must be a lot to see and we really like big adventures in small boats, so soon I was digging out old photo albums and slide carousels looking for pictures of some of our canoe trip days.

We have so many memories of big adventures, which were preceded by totally unsure planning stages. A big part of the fun in any trip is the planning, and I was recalling winter evenings around the kitchen table with our friends Al and Sue with a bottle of wine dreaming up paddle trips. We had all done some lake paddling together and, after we took a white-water canoe class and became reasonably proficient on moving water, we began trying out the salt water of Puget Sound. We did overnight trips to Blake Island and tide float trips up and back on Hammersley Inlet, just so we could say we had paddled canoes around Cape Horn. Hope Island, just inside Deception Pass, was a great two-night trip, as was Pelican Beach on Cypress Island.

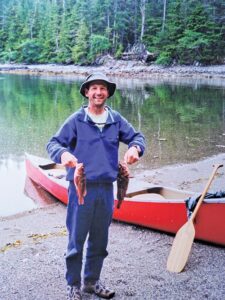

At some point Al and I decided to try a bigger trip and we loaded up my canoe and headed for Campbell River. From there, we took the ferry across to Quadra Island and launched into our first 10-day trip. We made it through some amazing water up to the Octopus Islands and ran some big ripping currents through Hole in the Wall Pass. Beach camping with pilot bread and rockfish dinners on the ol’ Svea camp stove and steel pan cookware was the plan of the day. I still love how that stove was lit; a little white gas was poured on it and we tossed a match to heat it up and that was all we needed. We came back home to convince our wives that this was about as much fun as could be had.

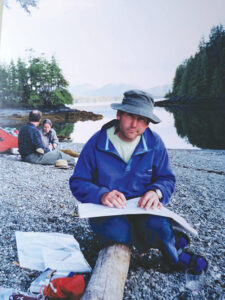

They believed us, so we began looking at charts and maps, wondering how far we could go in these tiny boats. Haida Gwaii looked interesting and possible, if daunting, so we did our research and talked to a guide in Moresby Camp who told us he would take us south into the wild on a big Zodiac and dump us on a beach wherever we wanted to go. I don’t remember how we decided, but we chose a tiny island called Swan to be let go on. It was 100 miles from Moresby, so we had to paddle about 10 miles per day to get back in our allotted time, which seemed reasonable. I remember the ride in the Zodiac being very cold and long at 30 knots, and finally getting to our destination. Doug, our guide, helped us unload our piles of gear onto the beach and drew some directions on our charts. He showed us where we could find water, where the abalone were and how to pound them, and then he waved goodbye, leaving us standing on the beach wondering what we had gotten ourselves into.

After settling down and looking at charts, we chose to spend our first day paddling a relatively short four miles of exposed water of Hecate Strait. Tekla writes in the journal: “Left Swan Island and headed east to the Copper Islands. Grey skies, headed around to the ocean side and I was scared. I felt like if the ocean decided to, it could pound us to pieces on the rocky shoreline. Looking out at the ocean from a tiny canoe traveling between rocky islands the ocean looks ominous.”

We were in small swells in tiny boats, and we all felt awe at the power the ocean held over us. The weather stayed calm as predicted, but this was our first taste of just how small you can feel in an island wilderness. It was powerful.

In July at 52 degrees north latitude the evenings are long and our first evening in Haida Gwaii was most enchanting. Ravens perched in the trees behind our camp making most extraordinary sounds like water dripping in an echo chamber and speaking a language we didn’t quite understand between the drips. It was easy to imagine they were telling us something about the long history of this place.

In the morning after groat cakes and coffee we slowly paddled into Burnaby Strait and through Dolomite Narrows. It was low tide and we could see the remarkable variety of sea life among the rocks in the crystalline waters. These islands are known for endemic sea life, creatures found nowhere else on earth, kind of like a northern Galapagos.

It was a drizzly low sky day and I had a song I disliked playing on an endless loop in my head, which made me irritable. It was cold and wet and I remember thinking, “Wait, why is this fun?” The question itself made me even more irritable. In the midst of a crystal-clear shallow channel floating above thousands of bat stars that were all the colors of the rainbow, and all manner of anemones and sea slugs surrounded by soaring snow capped mountains, my surly attitude suddenly seemed ridiculous. I was determined to change it. It helped when we ran into a group of kayakers who were on a guided tour from a “mother-ship” cruise. It was three couples on a large sailboat being shuttled around by a boat captain who knew the islands—they had soft dry bunks to sleep in every night and someone cooking dinner for them, that sounded nice.

At some point during the day, the drizzle turned to floating mist that faded into the atmosphere; the dark gray turned light gray and the sun burned its way through the seemingly impenetrable sky. I suddenly felt euphoric. Yes, this was fun! But it was more than fun. I was learning about myself in conditions that seemed difficult at the time and understanding that the best things in life are not necessarily easy. My spirit cleared with the weather and we made it to a beach camp on Kat Island and broke out the box wine. We were in paradise.

The following days were filled with light and dark, black bears on the beach, sandhill cranes rising from the beach, rain and sun. We did a 6 mile open water crossing to Hot Springs Island for a glorious soak in hot water surrounded by scenery so beautiful it defies description, because you can’t insert the feelings into the words of any description.

We visited Tanu, an ancient Haida village site and the watchman there walked with us around the village that had long since been rounded into mounds of thick luxuriant moss. It was a haunting yet marvelous place.

Long days of paddling, sleeping on rocky beaches, and challenges innumerable finally led us to our last day of paddling. I think we were all ready for some comfort and hot food. It was raining so hard on that last day that we had to bail water from the boats as we paddled. At least it was warm rain, in the 50s. We were all wearing rain gear and Teva sandals, and were thoroughly soaked from rain and sweat as we finally made it to Moresby Landing. Here, we began the long transition back into “real life”, which we began to question. Which life is more “real”—the one where you do what you must to survive or the old paycheck life that we were all going back to? We weren’t quite sure.

The four of us did several more long canoe trips before the “paycheck life” allowed us to buy into bigger boats and different adventures, but we still talk about Haida Gwaii. That trip changed all of us.

Now, we’re looking at charts and distances again, dreaming of the possibilities of having a picture of Sea Lab in front of a glacier on our wall for someone to ask about. I think it is possible!

—real life doesn’t get better than this!

Dennis and his mate, Tekla, reside in Auburn, WA and usually keep Sea Lab in the water at Tyee Marina.

Dennis Bottemiller

Dennis and his mate, Tekla, reside in Auburn, Washington and usually launch from Point Defiance to spend time on Sea Lab, their C-Dory 22 affectionately nicknamed “Boatswagen Bus.” When not playing with boats or guitars, Dennis can be found tending tropical Rhododendrons at the Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden.