The man by the fire pit was getting weepy. Sure, it was late and a number of microbrews had been sampled, but he was clearly moved by something deeper than alcohol or fatigue. “I haven’t heard those old songs in ages,” he said, turning to his daughter beside him. “I used to sing them with my dad.”

As the fire turned to embers and the group began heading to their boats for the night, he lingered, flipping through the songbook one more time to savor the music of his youth. One of the elders of our sailing club, he had always seemed aloof and unapproachable to me. Yet now he looked at my husband Frank, who had provided the evening’s impromptu entertainment, with misty-eyed appreciation. Not for the first time, I marveled at how music can bring generations of boaters together. Like just about everything, music is better on a boat or a dock, offering the perfect way to bond with fellow cruisers.

Early Songs of the Sea

Music has always been important aboard boats along the Northwest coasts. Indigenous seafarers in cedar canoes approached the ships of 18th century explorers with welcome songs, greeting Captain James Cook, for example, with music of “a very agreeable harmony” when he sailed into Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island in 1778. Cook responded in kind, ordering his crew to “to lay a tune” with a fife and drum. The Native musicians countered with another song, prompting the British sailors to bring out their French horns.

Captain George Vancouver recorded similar observations in 1793 on his voyage to the Northwest coast. “The chiefs generally approached us with the ceremony of first rowing round the vessels,” he wrote, “singing a song that was by no means unpleasing.”

Cook further observed the Native canoeists striking “their paddles against the sides of their boats with such exactness as to produce but a single sound,” adding that “each strain ends in a loud and deep sigh, uttered in such a manner as to have a very pleasing effect.”

The canoe songs of Indigenous people, sometimes accompanied by drums, rattles, and whistles, reflected the rhythms of paddling. Today, Northwest tribal members continue to incorporate music into the Annual Canoe Journey through their ancestral waterways. [Erna Gunther, Indian Life on the Northwest Coast of North America; The Journals of Captain James Cook; The Voyage of George Vancouver, 1791-1795, vol. III].

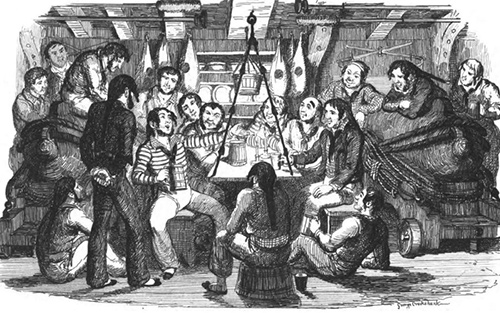

Rhythm was key to songs of the sea. The recent sea shanty (or “chantey”) craze on social media rekindled an interest in the early music of tall sailing ships, which used rhythm to help sailors perform repetitive tasks in sync. It is easy to imagine the crew operating a heavy capstan or windlass in unison to the refrain of “Way hey, blow the man down…” Sea shanties borrowed heavily from the music of enslaved people who sang rhythmic songs when loading ships from the dock.

In addition to work songs, off-duty sailors played fo’c’sle songs on the foreword deck for entertainment. The regular, heavy tempo and “call and response” format of these songs encouraged participants to join in, particularly during the chorus. “The Wellerman,” a whaling song from the 19th century, became a viral hit on TikTok during the height of the pandemic, as it was repeatedly shared, remixed, and embellished. Mariners baseball fans now sing “Soon may the Wellerman come / To bring us sugar and tea and rum,” dancing to its catchy beat at games in Seattle.

For all their jaunty, festive vibe, sea shanties have a dark side, often describing the miserable conditions on board, the dangers at sea, and a longing for home or port. Some lyrics are racist. Yet, a few short years ago some of these old songs spoke to a new generation, who, when faced with the despair of a Covid-19 lockdown, bonded over shared hardships, celebrating camaraderie and resilience.

Sing Me a Song

Every cruise presents an opportunity to continue maritime musical traditions. Frank and I have friends that carry a karaoke machine on board and we know people that have hosted a brass band on their ample-sized bow. For years, we heard about a legendary “dinghy concert” at Prideaux Haven in Desolation Sound, where entire bands played from the stern of a host boat. Our friend Todd, who attended this event one summer, was most impressed by the large audience of small boats packed into the inlet. “If you saw someone you knew 10 dinghies down,” he recalled, “you’d just swim to them. It was the easiest way to get there.”

Some boaters, particularly those just starting out, may prefer smaller, simpler gatherings with compact instruments and music that can be easily shared with all participants. And we have found that nothing works better than songs about boats and cruising. It’s what we all have in common, after all.

Our repertoire includes music that people are likely to recall fondly — popular tunes that go beyond sea shanties and “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” Beloved ballads such as “Sloop John B” by the Beach Boys and Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” with its haunting riff, are crowd pleasers. While the music is about boats, mostly focusing on recreational cruising, it addresses universal themes and stories that resonate widely.

Songs about the joys of travel and voyaging are always appealing. Consider, for instance, the lyrics to Enya’s “Orinoco Flow”: “Carry me on the waves to the lands I’ve never been … Sail away, sail away, sail away…” Or Jimmy Buffet’s “Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes,” which includes a line many of us can relate to: “So many nights I just dream of the ocean, god I wish I was sailing again.” Boats, according to country singer Kenny Chesney, are “vessels of freedom” — and who can argue with that?

Boating songs can promote family and a sense of continuity. Buffet forges a charming connection with his daughter in “Delaney Talks to Statues,” for instance, assuring her that “Shells sink, dreams float / Life’s good on our boat.” In “Son of Son of a Sailor” he explains that his love of the ocean is inherited, singing “the sea’s in my veins, my tradition remains.”

Some boating songs are bittersweet, and lost youth is a common theme. Buffet’s well-known “A Pirate Looks at Forty” evokes nostalgia for his personal past as well as for bygone eras, characterized by the “switch from sails to steam.” One of my favorites, “The Skye Boat Song,” was recently given new life by the series “Outlander.” This dreamy tune is not the original song about Bonnie Prince Charlie, but a musical rendition of a poem by Robert Louis Stevenson, which begins “Sing me a song of a lad (lass) that is gone…” It is as much a longing for a place as it is about childhood, and though it recounts a journey through the waters of Scotland, the lines “Billow and breeze, islands and seas / Mountains of rain and sun…” could easily have been written about the Salish Sea.

While many boating songs are fun, some descend into melancholy. Sting’s “Valparaiso,” for instance, offers a poetic account of his heavy burdens: “And every road I walked would take me down to the sea / With every broken promise in my sack…” If you haven’t heard this mournful, lovely song, which has the feel of a historic tune, I recommend checking it out. One of the best-known songs in this category is Otis Redding’s classic “Dock of the Bay,” which describes how his self-reflection slides into inertia as he watches “the ships roll in” and then watches them “roll away again.” Unable to do “what ten people tell me to do,” Redding concludes that “nothing’s going to come my way,” so he sits on the dock “wastin’ time.” So evocative are his lyrics that you can almost smell the salt air as you feel your energy draining.

In a different way, Buffet’s “Margaritaville” also explores the theme of “wasting away.” Although its lively melody gives the song a light feeling, it is self-reflective, and, at its heart, regretful. While there may be “a woman to blame,” the singer comes to realize that it’s his “own damn fault.”

Hard partying is another recurring theme. “Margaritaville” celebrates “that frozen concoction that helps me hang on,” as the singer examines his choices, as well as his new tattoo, through a boozy haze. “Get yourself a coozie,” advises Little Big Town in the song “Pontoon,” and “reach your hand down into the cooler.” Meanwhile the “president” of the Redneck Yacht Club pops “his first top at 10 a.m.,” and members make “waves in a no-wake zone.” Such descriptions of the sailing lifestyle go way back. What do you do with a drunken sailor? Boaters have been pondering that question for centuries.

Several boating songs explore loftier themes of perseverance and healing. One Beach Boys song, for instance, presents a litany of nautical complaints, each ending with the refrain “Sail On, Sail On, Sailor.” Styx’s “Come Sail Away” — revealed in an informal poll at my yacht club to be a favorite boating song — is about endurance and persistence (“But we’ll try best that we can / To carry on…Come sail away with me, lads”).

The idea that sailing can mend the soul is widespread. “The canvas can do miracles,” promises Christopher Cross in “Sailing.” Crosby, Stills & Nash’s “Southern Cross” fits this category. I have always loved this tune for its references to a “noisy bar in Avalon,” sailing into Papeete, and seeing the Southern Cross for the first time – all of which I have experienced and can relive through the song. Yet “Southern Cross” is about much more than travel and adventure — it tells a story of how the sea can restore us, in this case helping a sailor recover from a breakup.

Across this extraordinary range of perspectives and themes, these maritime songs help connect boaters, who recognize their own lives and experiences on the water.

for small boats.

Musical Instruments on Board

Frank and I use several paper song books and paper sheets that can be distributed, but they take up space on our small boat. Mostly we consult a tablet, accessing apps such as SongbookPro and OnSong. And the internet is a rich source for learning basic chords.

Which instruments are best on board? Some musicians find that smaller instruments, which are easier to store and carry, work best. Many of our friends prefer ukuleles and small traveling guitars, which are portable and relatively inexpensive, as well as easy to learn for those just starting out. Frank and I bring a guitar and a mandolin on our longer trips, which increases the versatility and appeal of our repertoire, though they can be a hassle to transport. Our brother-in-law, Steve, a professional trumpet player, brings a pocket version of his instrument on his boat. Water and condensation can damage musical instruments. For this reason, our friend Cheryl uses a carbon fiber guitar, which is relatively “immune to the wet environment” on board.

When Steve plays a tune on his pocket trumpet, surrounding boaters typically clap and request an encore. But he’s an excellent musician who knows how to please a crowd. It is important to consider neighbors when playing loud instruments; we find that the sound of trumpets, banjos, and mandolins can carry far, potentially disturbing others. Cheryl is especially conscious of noise. One evening, she closed all the hatches and quietly strummed her guitar in the cabin. Soon came a knock on her hull. “Oh, no…” she worried, assuming that another boater had come to ask her to keep it down. Instead, she emerged to find a man with a guitar, asking if he could join in. There really is nothing like music to bring boaters together.

Lisa Mighetto is a sailor and historian living in Seattle. For information on music and boating, she is grateful to Matt Herinckx, Olympia Yacht Club; Steve Stanley, Oakland Yacht Club; and Todd and Cheryl McChesney, Seattle Yacht Club.

For more information on Annual Canoe Journey: preservewa.org/carrying-traditions-by-canoe-the-tribal-journeys-movement-in-washington/ and muckleshootcanoejourney.com/ Maritime music events, including sea shanties: maritimefolknet.org/