It is hard to imagine a more scenic location for a lighthouse than Point Wilson. Marking the convergence of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Admiralty Inlet, it offers sweeping views of both waterways — and on a clear day the snowy peak of Mount Baker is visible in the distance.

This beacon, constructed more than a century ago, remains one of the tallest and most architecturally striking in the Salish Sea. Its location on a sandy spit at the entrance of Puget Sound also makes the Point Wilson Lighthouse one of the most strategically significant.

A Strategic Location

Captain Vancouver of the Royal Navy named the point in 1792 to honor his colleague George Wilson. For centuries, Native peoples had navigated their shallow-draft canoes along the low-lying spit, which the Chimacum called Kam-kam-ho and the S’Klallam called Kam-Kum. But the larger, deep-draft vessels of the Europeans proved challenging to sail through these unfamiliar waters, with shoals, riptides, fog, and wind increasing the danger to mariners.

By the late 19th century, hundreds of vessels had been wrecked or forced aground. The church bell that rang during foggy days in nearby Port Townsend was not adequate to guide the steady flow of ship traffic. As Port Townsend grew into a boom town and a bustling center of international maritime commerce, it became clear that improved navigational aids were essential.

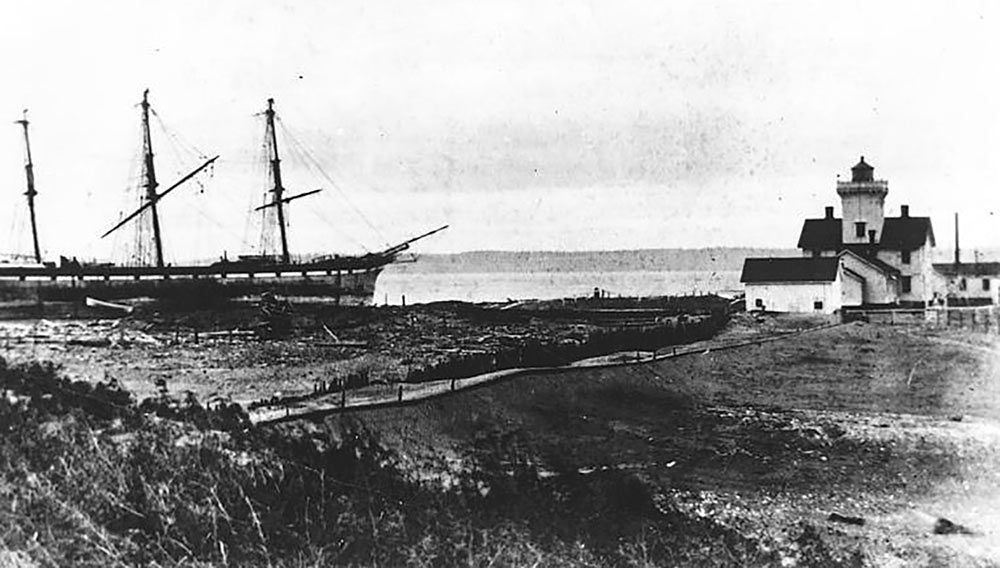

The first light station at Point Wilson became operational in 1879. The complex of buildings, which sat on the far end of the spit, included a wood-framed building that served as a dwelling for the two keepers and a light tower projecting from the roof. A fog signal structure housed a steam whistle that used water stored in a cistern.

An incident one foggy evening in September 1896 demonstrated the need for a more reliable fog signal, which was not functioning at that time due to lack of water. That night, the vessel Umatilla struck rocks west of the lighthouse and began to sink. The captain opted to run the ship aground on the beach near the beacon, where the passengers were safely offloaded. Damage to the vessel and cargo was substantial, however, prompting calls to upgrade the light station.

“The commerce of the Sound is growing,” the Seattle Daily Times explained, “and if there is any appliance known to navigation that can guide vessels in a fog past Point Wilson it should be provided.” (September 30, 1896)

The supply of freshwater at the Point Wilson Lighthouse improved with the construction of Fort Worden adjacent to the beacon. Built at the turn of the 20th century, this military installation was part of a trio that included Fort Casey at Admiralty Head (see 48° North, January 2022) and Fort Flagler south of Port Townsend. Known as the “Triangle of Fire,” the three forts were strategically placed to repel enemy vessels entering Admiralty Inlet — and all were paired with lighthouses.

The New Light

In 1914, the United States Lighthouse Service replaced the aging wooden tower at Point Wilson with a new beacon constructed of concrete and masonry, also located on the spit. With a height of 46 feet, the new lighthouse was the tallest on Puget Sound. It included the fourth-order Fresnel lens from the old tower, which was illuminated with a new 120-watt electric bulb instead of an oil-burning lamp. A new chime diaphone foghorn activated by compressed air replaced the old steam-powered fog whistle. The tower was octagonal in shape to withstand high winds.

Designed by Carl W. Leick, a German immigrant and prolific lighthouse engineer, the Point Wilson station combined the latest technology and architectural sophistication. Leick worked throughout Washington and Oregon, and his designs included the beacons at Mukilteo (see 48° North, September 2021) and Alki Point (see 48° North, May 2022). The Point Wilson Light was one of Leick’s last designs, and one of his most architecturally refined. According to one source, “Its clean lines, graceful proportions, and steeply pitched roofs all draw the eye upward to the top of the octagonal tower and its elegant Fresnel lens.”

A Noteworthy Keeper

While life at the Point Wilson Light Station was characterized by daily maintenance chores and constant vigilance, the keepers were also affected by major historical forces and significant events. During World War I, for instance, the U.S. secretary of commerce urged lighthouse staff to cultivate gardens in anticipation of food shortages. Head Keeper William Thomas enthusiastically complied, despite the difficulties of growing vegetables in the sandy soil at Point Wilson. Summarizing his efforts to the lighthouse inspector, Thomas explained that after four attempts, he was able to produce some beans, which he salted and canned.

“The yield was good,” he reported, “but of course of small quantity, as space was limited.” His onions and lettuce “were splendid,” and he was able to grow peas, potatoes, carrots, and squash as well.

Thomas, who served at Point Wilson for 12 years, continued to struggle with the “bare sandy spit” there during the 1920s. To combat the erosion caused by fierce winds, he planted Kentucky bluegrass around the beacon. But the seeds did not sprout. Instead, Thomas discovered that they had blown and taken root 10 miles north, on the grounds of the Smith Island Lighthouse, which had turned a radiant, if mysterious, green.

“It’s rather peculiar,” confessed the Smith Island lightkeeper during Thomas’ visit. “We never did plant any seed here.” Thomas quickly concluded that it was his bluegrass. “I planted it this spring over at Point Wilson,” he informed his colleague. “And now you’ve got it.” (Seattle Daily Times, March 14, 1926)

Thomas further distinguished himself when he became part of a rescue effort involving the collision of the passenger liner S.S. Governor and the S.S. West Hartland in 1921. The Governor, which was traveling inbound to Seattle, failed to yield to the West Hartland as that ship departed Port Townsend. Thomas, hearing the crash and ship’s whistles, notified the authorities in Port Townsend, allowing for a quick response.

Within half an hour, the Governor sank off Point Wilson. Although eight people lost their lives, most passengers were saved, and the tragedy could have been worse. Thomas’ long service at Point Wilson may have led the Seattle Daily Times to describe the head keeper “as widely known among mariners as any other man on the Pacific Coast” (March 14, 1926).

The Point Wilson Lighthouse Today

The beacon remains an icon in the Port Townsend area, easily accessed from Point Hudson Marina (watch for tide rips, especially during an ebb). Its fourth-order Fresnel lens continues to shine, flashing alternate red and white every five seconds. To learn about tours and renting the head keeper’s restored house, visit www.pointwilsonlighthouse.org

This Point Wilson website offers enthusiastic encouragement to visitors as well as useful information, claiming that “no other location is as dramatic and beautiful.” For a sense of place, see the 1982 film “An Officer and a Gentleman.” Although it may seem cheesy and dated by today’s standards, the movie captures the power of the natural environment in this spot where the Strait of Juan de Fuca meets Admiralty Inlet, with Fort Worden and the Point Wilson Lighthouse as compelling backdrops.

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor living in Seattle.