Fortunately, it didn’t move outside the main channel.

We felt the first bump just north of the train bridge on the Swinomish Channel.

“What the hell?” I thought. “We are definitely right in the middle of the channel. We shouldn’t be touching bottom here!”

We were through the obstruction so quickly, I barely had time to react and throw the engine into idle. It was a very soft impact, likely just the normal soft mud and sand that covers this well-worn route to and from the San Juan Islands. The depth gauge quickly returned to the 12 to 14 feet that it had been reading prior to that.

I figured it had to be some sort of anomaly. I have transited this well marked, approximately 10-mile channel on the east side of Fidalgo Island maybe a dozen times before in sailboats of various sizes, and I had never once touched bottom or even gotten close.

Was it time for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to dredge the channel again? Clearly, it must be their fault for letting the bottom creep up in places.

We kept motoring south toward La Conner, on our way back down to Puget Sound after completing a few weeks of projects on the boat in Anacortes. It was some welcome downtime to play in the San Juan Islands for a few days before the summer cruising season really kicks into high gear.

Although we typically cross the Strait of Juan de Fuca on our travels to and from the north, I have always found the Swinomish Channel to be an interesting and fairly picturesque passage when we have used it. Navigating it is a fun challenge for a number of reasons, including using the ranging marks in the south entrance to keep mid-channel and also trying to figure out the mysterious current that has bedeviled mariners probably since the channel was created.

I was actually feeling pretty smug just before we bumped. I wanted to make sure the current was flowing in the right direction for us, and I had successfully used the rough rules of thumb for the Swinomish Channel currents to plan our passage on this late spring morning.

The current in the channel can run several knots, so it is something that we full-displacement boat owners need to take into account. In general, the current flows north between 2.5 to 4 hours before and after high tide, plus 30 minutes, as measured at the Seattle tide stations. It generally flows south about 2.5 to 4 hours before and after low in Seattle, plus 30 minutes.

On we went toward La Conner. I kept a very close eye on the depth sounder and our position in the channel. I definitely didn’t want to drift out of the deepest part of the ditch.

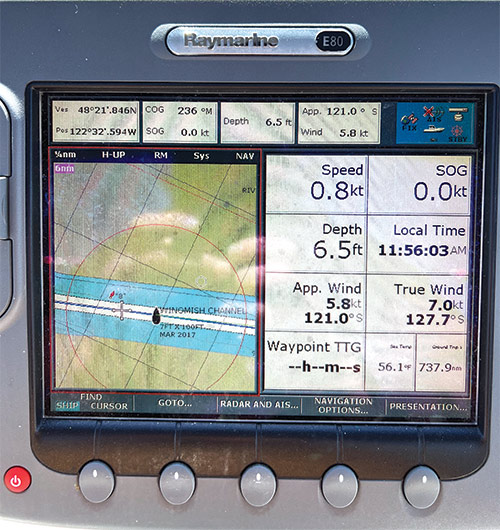

Once again, I saw depths ranging from 12 to 17 feet, and all was well. Then suddenly, the sounder dropped to 10 feet. Then 8. The shallow depth alarm rang from the multifunction display just before we again bumped the bottom, with downtown La Conner only a few hundred yards ahead of us. Crap!

Yet again, it was a very soft impact and we were quickly through it. But I was flummoxed. What was going on? Yes, we were getting close to low tide, but this seemed ridiculous. They were definitely overdue to dredge the channel, clearly.

The Swinomish is dredged to a width of 100 feet and a minimum depth of 7 feet, at least according to the chart I was reading. And our Passport 40, Rounder, draws just shy of 6 feet.

The tide was still falling as we continued on our way south. I knew that it was supposed to be at its lowest at 11:47 a.m. and we still had about 30 minutes to go. I thought about stopping at La Conner, grabbing a bite for lunch and waiting a few hours for the tide to start rising again. But the thought of losing this positive current and a desire to make it to our planned stop that afternoon in Langley convinced me that we should continue on.

Somewhat dismayed by the two groundings, the plan was to take it slow, be careful, and assume that the south entrance to the channel would be dredged to the charted depths.

For the next 30 minutes or so, I was pleased with how things were working out. While the depth meter hit an uncomfortable 9.5 feet as we made the 90-degree turn at Hole in the Wall, it mostly stayed in the 11 to 12-foot range.

As we traversed the straightaway on the south end of the channel, I kept to dead center, using those ranging marks to confirm the GPS position I was seeing on the multifunction display.

I was close to breathing a sigh of relief as the last of the red buoys marking the shallow water of the channel hove into view and then crept closer. Just a few hundred yards to go.

Then, for the third time that day, the shallow water alarm went off as the depth sounder quickly plunged from 12 feet down to 6 and then 5. We were already going slow, and the boat came to a gentle stop as we stuck fast in the middle of the channel. There was no bumping through this time.

The current was still moving south at about 1 knot. Rounder slowly turned perpendicular to the channel and heeled over about 5 degrees to starboard as the current pushed against our beam.

After checking the bilge and confirming that we were not moving toward either side of the channel, we settled in to wait. The crew was okay. The boat was okay. But my ego was in tatters.

I knew that we just had to wait for the tide to rise. We didn’t feel the need to call for help or to panic. We made a second pot of coffee and kept a close watch to make sure nothing in our situation changed for the worse.

Of the dozens of boats that passed us, only three slowed to check on us or offer help. Luckily, one of them was willing to use his depth sounder to let me know how shallow it was ahead of us. He checked, came back and told me that I was looking at about 5 feet for the rest of the channel.

As I sat there pondering what went wrong, I soon discovered my error. It turned out that it was a minus 2.5 foot tide that morning. In all my efforts to figure out the time and direction of the current in the channel, the one thing I failed to take note of was just how big that low tide would be. I pounded my forehead on the wheel of my stuck boat for making such a stupid error.

The 7-foot depth the Corps dredges to is for a zero tide. When you subtract 2.5 more feet from that, you end up aground in a sailboat.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had done their job. It was a skipper in a hurry who didn’t do his.

About an hour later, as the water crept higher, the wake from a passing boat jostled us just enough to break us free from the bottom’s grip. We turned the boat back toward La Conner, knowing that at least there was enough water for us if we took the same route again.

A few hours — and a few more feet of water — later, we made it through that last stretch of the channel.

The crew was fine. The boat was fine. And the skipper had once again learned not to get complacent when tackling a tricky bit of navigation.

Marty McOmber is a Pacific Northwest sailor, writer, and strategic communications professional. He is currently working on refitting and improving his 1984 Passport 40, Rounder, for continued cruising adventures near and far.