My first boat was a wherry — a sturdy, open-hulled vessel that could be rowed or paddled. My husband Frank and I took that boat everywhere around the Salish Sea, often to places I wouldn’t dream of venturing in an 18-foot craft today. We chose Nisqually Reach in the South Sound for our maiden voyage. It was a sunny April day with smooth seas and stunning views of Anderson Island and Mt. Rainier. We poked around the salt marshes of the Nisqually Delta, eventually heading toward open water, where we bobbed up and down with the pigeon guillemots, rhinoceros auklets, and western grebes — birds not easily visible from shore.

For me, this was an introduction to a new world, one that I could experience right at water level, from a perspective not allowed by larger sail and power boats. Yet for all the natural beauty of Nisqually, what I remember most was encountering the rusted and barnacled railing of an old tugboat that likely sank many years earlier. Frank and I repeatedly circled the partially submerged boat, peering down into the broken hull.

“Standing over the remains of the shipwreck is like looking at a skeleton in an opened tomb,” wrote Jennifer Kozik in the introduction to her book Shipwrecks of the Pacific Northwest (2020), “The bones of the ship are saying they have more [stories] left to tell.”

We were floating, not standing, but the encounter with the wreck awakened our curiosity. What happened to this boat? Who was at the helm? Was anyone injured, or worse? After our Nisqually trip, we learned that several vessels had wrecked near the shore in this area. The decaying remnants in fact have attracted many visitors who are as interested in the human drama as they are in the natural environment.

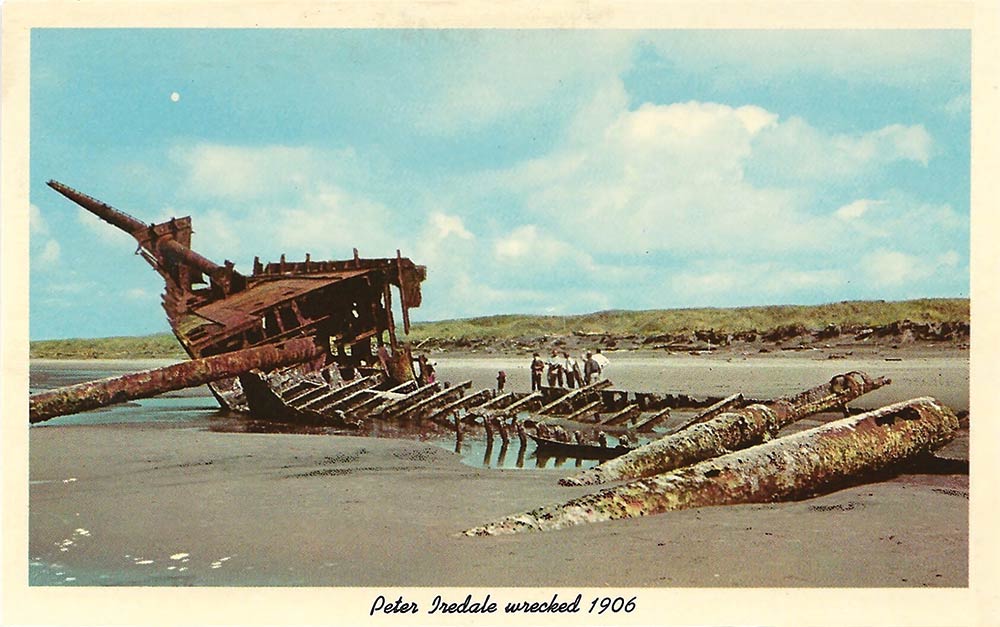

Intrigued, I began to seek out shipwrecks. One of the most accessible was the Peter Iredale, a four-masted barque that ran ashore on the Oregon coast in 1906. Still visible today at Fort Stevens State Park, the rusted bow and broken mast of the beached vessel rise out of the sand, reminding tourists of the perils of the Graveyard of the Pacific. Throughout the centuries, thousands of ships have wrecked on this stretch of coastline, which extends from Tillamook Bay in Oregon northward to Cape Scott on the tip of Vancouver Island.

One of the worst disasters in terms of casualties was the SS Pacific, which went down southwest of Cape Flattery in 1875, killing more than 275 people. The recent discovery of the wreck at the bottom of the ocean has sparked international interest. While much of the attention so far has focused on the salvage operation, it is clear that the Pacific has many stories to tell about the Civil War, gold rush fever, maritime transportation, and social hierarchies. And that’s just scratching the surface.

Setting the Scene

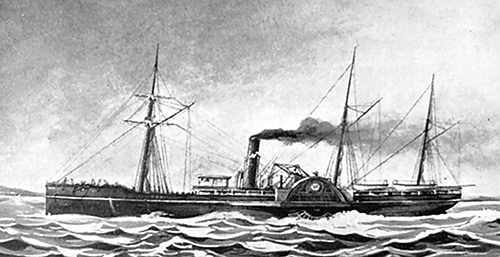

In November of 1875, the SS Pacific was well past its prime. Built in 1850 in New York, this 225-foot sidewheel steamship saw decades of hard service, first running between the Isthmus of Panama and San Francisco during the California Gold Rush. During the late 1850s, the wooden ship began carrying passengers from San Francisco to the Columbia River. The Pacific was heading downriver from Portland in 1861 when it struck Coffin Rock in the fog, sinking immediately. This was not the end of the story, as the ship was raised, pumped out, repaired, and returned to service, which included voyages to Southern California. A decade later, the Pacific was retired and left on the mudflats of San Francisco Bay.

But the discovery of gold on the Stikine River in the Cassiar District of Northern B.C. pressed a number of old vessels back into service to transport miners and speculators to and from Canada. The Pacific was again resurrected and purchased by the Goodall, Nelson and Perkins Steamship Company. The US Steamboat Inspection Service pronounced the ship seaworthy, though the latest round of repairs was cosmetic. So rotten was the timber under the new coat of paint that the men working on the refit claimed that the “waterlogged wood could be scooped out with a shovel” (Gare Maritime, June 28, 2007).

More than 275 passengers had boarded this deteriorating ship when it left Victoria bound for San Francisco on November 4,1875. Some got on at ports in Puget Sound, and many were last-minute additions who remained anonymous. The ship’s manifest listed “41 Chinese” who were unnamed. The cargo included 280 tons of coal, 2,000 sacks of oats, 11 casks of furs, 31 barrels of cranberries, two cases of opium, six horses, and two buggies. Also on board was an estimated 4,000 ounces of gold. Observers at Port Townsend claimed that “the vessel leaked so badly that there [was a large quantity] of water in her lower hold, and the grain was not put down there for fear of damaging it” (New York Times, Nov. 25, 1875). As the Pacific departed, several reported that a great crowd of people completely covered the deck, and the vessel was listing as it headed out to sea. The five lifeboats were not adequate for all the souls on board.

Captain J. D. Howell was in command. A seaman educated at Annapolis before the Civil War, Howell was the young brother-in-law of Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy. Before landing in the Pacific Northwest, Howell had been arrested, imprisoned, and released several times for his association with Jefferson Davis and for his service on a rebel gunboat in the Confederate States Navy. Just 34 years old in 1875, Howell made several fateful decisions on the SS Pacific. First, he reportedly delayed the ship’s departure while he nursed a headache, fueling later speculation that he was suffering from a hangover. Timing was everything. Had the Pacific left sooner, events might have unfolded differently. Second, Howell ordered his crew to fill at least some of the lifeboats with water to counterbalance the listing of the ship — a seemingly practical measure that would have dire consequences.

Disaster at Sea

The night of November 4 was cold and dark, and the Pacific made slow progress steaming into the wind on its journey down the coast of Washington. At 10:00 p.m., many of the Pacific’s passengers had retired to bed when a sudden jolt shook the ship. They had collided with the Orpheus, a 200-foot full-rigged sailing vessel moving northward, bound for Nanaimo, B.C. The crew of the Orpheus assumed that the Pacific was not badly damaged and continued on, focusing on their own repairs, which they attempted while underway. The sailing ship eventually veered off course and wrecked on the rocks of Cape Beale on the west side of Vancouver Island, with all those on board escaping to the shore. The passengers aboard the Pacific were not so lucky.

Soon after the Orpheus continued on its way, the Pacific began to break apart. Within minutes, the wooden hull was breached and water rushed in, sending the people on board into a panic. Henry F. Jelley, a 22-year-old passenger, and Neil O. Henly (or Henley), the ship’s 21-year-old quartermaster, were the only two survivors. Both provided accounts of the horrific scene on deck, which included a small boy being crushed to death in the chaos and lifeboats (already filled with water) swamping “amid the shrieks of women and the despairing cries of the men” (New York Times, Nov. 25, 1875).

The ship sank quickly, leaving pieces of debris, and according to Henly, a “mass of human beings” screaming and struggling to stay afloat. “In a little while it was all over,” he recalled. “The cries had ceased” (quoted in James A. Gibbs, Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast, 1957). Jelley was able to climb onto the wreckage of the pilothouse and was rescued a few days later by a ship that delivered him to Port Townsend, where the world learned of the disaster for the first time. The revenue cutter Oliver Wolcott was dispatched to search for survivors. Meanwhile, Quartermaster Henly had clung to a piece of the hurricane deck along with seven or eight fellow castaways, including the captain, second mate, and a woman passenger. A few hours later heavy seas washed over the makeshift raft, sweeping away the captain and several others. The remaining passengers died of exposure and slid into the water, leaving only Henly, who was rescued by the Oliver Wolcott. He had spent nearly 80 hours adrift at sea.

An important figure in the Pacific story, Henly seemed to land on his feet despite the ordeal he endured. “Quit the sea?” he later asked. “No, I kept right on.” Described as a man of “bright blue eyes” and rosy cheeks, Henly continued to work as a seaman, eventually becoming superintendent of boats at the McNeil Island Penitentiary (quote from 1942 in Seattle Daily Times, Jan. 8, 1953).

The news about the Pacific was devastating to the region. “The catastrophe is so far-reaching that scarcely a household in Victoria has not lost one or more of its members,” wrote the Daily Colonist. “In some cases entire families have been swept away” (quoted in Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast). The aftermath of the Pacific disaster seems eerily similar to that of the Titanic, which sank 37 years later. “Wrecks — especially big ones like the Pacific — challenged the optimism of settler society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” explained Coll Thrush, a history professor at the University of British Columbia. At the same time, “they deepened settler claims to the region through the trauma and loss of maritime disaster” (communication with the author).

Today, a weathered monument stands in Seattle’s Lakeview Cemetery commemorating Howell, who “perished at sea” on November 4, 1875. Meanwhile, other drowned passengers, including the anonymous Chinese, remain unnamed and largely forgotten.

Finding the Shipwreck

James A. Gibbs, a noted historian of shipwrecks, predicted in the 1950s that the story of the Pacific would inspire adventurers to “search for her hidden grave.” Yet he doubted such efforts would yield “more than a small pile of teredo-eaten planks” (Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast). Last year’s discovery of the sunken vessel by Jeff Hummel and Matt McCauley of Rockfish, Inc. may well prove this assumption wrong. “The state of preservation of this wreck is on par with any of the greatest shipwreck finds in the world,” Hummel commented recently. The team of excavators, which includes marine archaeologists and the non-profit Northwest Shipwreck Alliance, expects to retrieve “an absolute treasure trove of artifacts” (Daily Mail, Dec. 7, 2022).

Hummel and McCauley achieved notoriety in the 1980s when they raised a World War II plane from the bottom of Lake Washington. The pair searched for the Pacific for years, conducting 12 expeditions between 2017 and 2022. Using underwater equipment, including remotely operating vehicles, their team located the wreck south of Cape Flattery, around 23 miles offshore. Local fishermen provided a clue as to the Pacific’s position on the seafloor, netting pieces of coal later identified as having come from a mine that had supplied the vessel. Sonar images showed circular depressions near the wreck. Believed to be the steamer’s paddle wheels, these objects had separated from the ship and now lay partially buried in the seabed. The recovery of artifacts will take many years, and the descendants of shipwreck victims will have a window of time to lay claim to some of the items.

A lot of media attention has been focused on the gold that might resurface. Yet Hummel cites his interest in history and drive to bring the past “back to life” as the primary motivation of this operation. “The main thing that we want to do,” he explained, “is protect and preserve the site for future generations.” McCauley agreed, noting that while thrilled to have found the wreck, the team’s mood is somber and reflective. “We take this very seriously,” he commented. “This is not [a] woo-hoo party time kind of a thing.” There is much to be learned from the recovered artifacts and the team hopes to open a museum dedicated to the story of the Pacific. In the end, though, the wreck “is the final resting place of a great tragedy,” one that needs to be handled and interpreted accordingly (Courthouse News Service, Dec. 5).

Lore and Legacy

There is a mystique that surrounds most major shipwrecks. Accounts of the sinking of the Pacific — historical and modern — often describe the vessel as “jinxed,” “ill-starred” and “doomed.” James A. Gibbs began his history of the vessel as follows: “Death clad in all its hideousness rode the decks of the steamer Pacific….” (Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast). The story is told as high drama rather than a tale of misplaced faith in technology or inadequate safety standards in early maritime travel. Historian Coll Thrush, author of the forthcoming book Wrecked, has researched our fascination with maritime disasters. “I think it has a lot to do with the ‘romance’ of the ages of sail and steam,” he recently explained, “and of a time when as a society we had a more intimate and immediate relationship to the sea.”

Pieces of wreckage, whether excavated or washed up on shore, are revered and presented like relics. Years ago, when Frank and I chartered a sailboat in the British Virgin Islands, we spotted a marker buoy hanging in a bar on Anegada Island. “That’s from the Andrea Gail,” the bartender announced, proud of this remnant from the real-life fishing vessel featured in the movie “The Perfect Storm.” No matter that the artifact was found before the boat sank and the crew drowned. Its mere association with the 1991 tragedy, however indirect, gave the item status and an eerie power.

Our interest in such objects goes deeper than morbid curiosity. Like horror stories and movies, tales of shipwrecks and their relics allow us to view the formidable, unpredictable force of the ocean from a distance. We experience the fear and unease vicariously, from the safety of armchairs, museum displays, and (hopefully) stable boats floating above the wreck, just as I did years ago at Nisqually Reach.

Shipwreck artifacts offer a tangible connection to the people of the past, increasing our understanding of the history that has been hidden beneath the surface. As mariners, we have much to look forward to in the next few years as the “treasure trove” from the Pacific comes to light.

Additional Information

For more information on the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance and the SS Pacific, see: http://northwestshipwreckalliance.org/

The Vancouver Maritime Museum holds a wooden stanchion or frame that washed up on shore after the Pacific disaster. The words “all lost” are scribbled across, along with the initials S.P. Moody. See: https://vmmcollections.com/Detail/objects/12921

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor living in Seattle. She is grateful to the Coast Guard Museum Northwest for providing images and information for this article.