My “gateway boat” was a rowing scull with double oars and a sliding seat. I nearly fell in the water at Green Lake the first time I attempted to board this 18-foot wherry from the dock, and once I managed to climb in, I became lost in a tangle of limbs and oars, all of which seemed too long and unwieldy to propel the boat forward. I had little experience with boats, so this served as an introduction to the skills that would serve me well in larger boats over the decades: balance, strength, grip, and rhythm with crew and the natural environment around me. Rowers face backward, which heightens awareness of what lies ahead, requiring coordination with others or reliance on navigational senses other than sight. Eventually, I found myself gliding across the water with remarkable speed, if not grace. This experience opened a new world for me, one that included the thrill of exploring the lakes, channels, and inlets of the Salish Sea under my own power, in sync with my boat. Competitive rowing further connected me with local traditions, based on affinity for water, boats, and camaraderie with crew.

As a sport, rowing has long been important to the Pacific Northwest’s regional identity. The spectacle of shells skimming across Lake Union is as familiar to morning commuters along I-5 as the iconic sights of Mt. Rainier and the Space Needle. And the recent release of the film version of The Boys in the Boat, directed by George Clooney, and the exhibit Pulling Together, currently at the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI), indicate that rowing stories from the past continue to resonate.

REGATTAS PAST AND PRESENT

Competitive rowing was once the most popular collegiate sport in the United States. Former oarsmen from Cornell, Harvard, Yale, and other Ivy League schools brought it to the Pacific Northwest as they settled here during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At that time rowing clubs began to emerge in cities along the shores of the Salish Sea. These were elite clubs with a strong social component. In addition to races, the Vancouver Rowing Club, for instance, held “jolly dances” and “delightful hops” as well as sumptuous dinners for its “aristocratic” membership [Seattle Daily Times, March 10 and July 2, 1902].

The appearance of rowing clubs in our region coincided with the establishment of yacht clubs, revealing a connection between rowing and yachting. “Great attention is being laid to all health-giving sports,” noted an 1892 article in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “two of the foremost being yachting and rowing. With the advantages we have in beautiful and convenient waters, we should have a yachting and rowing club here very soon… “ [July 11, 1892]. The Seattle Yacht Club was formed that year. The Olympia Yacht Club, too, can trace its roots to a rowing club in south Puget Sound. Emerging at the same time, both yachting and rowing were leisure pursuits that employed techniques and skills once associated with the maritime industries essential to the growth of this region.

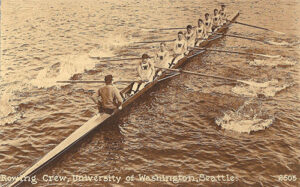

Seattle and the Salish Sea offer a network of waterways with a mostly temperate climate — conditions that allowed competitive rowing to flourish year-round. Accordingly, the University of Washington’s move from downtown Seattle in 1895 to its current location on Lake Washington sparked interest in establishing a rowing program. In 1903, with support from the local business community, the UW men’s crew rowed in its first intercollegiate race, defeating the University of California and launching a decades-long rivalry with the Cal Bears. Four years later, the Husky rowing program purchased its first eight-oared shell from Cornell University, soon becoming the dominant rowing team on the Pacific Coast.

In 1936 the UW crew was named best in the world after winning the Gold Medal in the Berlin Olympic games, foiling Hitler’s plan to showcase the Third Reich. Daniel James Brown’s best-selling book, The Boys in the Boat, tells the story of how these oarsmen with humble backgrounds broke through the classist barriers that characterized the sport to emerge victorious against all odds. The international attention focused on this crew, who rowed “like demons,” helped put Seattle on the map, galvanizing the city during the height of the Great Depression [Seattle Daily Times, July 15, 1936]. By the early 1940s, intercollegiate crew races on Lake Washington were drawing more than 200,000 spectators.

The “Great Race” captured additional public interest in 1941. That year UW crew brought two of their eight-oared shells to the Swinomish Slough to face Indigenous canoers. Native paddlers had traveled the Salish Sea in cedar canoes for many centuries, and they often participated in rowing regattas [see Seattle Daily Times, June 21, 1907, for instance]. The Great Race pitted two, 11-man racing canoes – Lone Eagle and Susie Q – against the Husky shells in a paddlers versus rowers competition. It is unclear who won, as publicity and kinship — not victory — was the point of this regatta. According to historian Bruce Miller, Native cedar canoes “represented a connection to the land, to the water, and more generally, to an aboriginal world view,” while the Husky rowers “represented the vigor of a community” then based on fishing and logging, activities “intimately connected with the sea” [”The Great Race of 1941: A Coast Salish Public Relations Coup,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Summer 1998].

During the second half of the twentieth century, focus on rowing shifted to other sports. Even so, the UW crew program continued to thrive, encouraging the development of non-collegiate clubs on Lake Union, Green Lake, Gig Harbor, Port Townsend, and other locations. The passage of Title IX in 1972, which prohibited sex-based discrimination in schools, ensured female access to the sport, boosting the UW’s women’s program that had started earlier in the century. In 1987 the annual Windermere Cup began pairing the UW crew with international competitors, starting with rowers from the Soviet Union. This regatta takes place the first Saturday in May, coinciding with the Seattle Yacht Club’s Opening Day festivities. Thousands of spectators typically line the Montlake Cut for the event, which marks the official “start” of boating season.

My sister-in-law Dianne rowed for Cal in this regatta in the 1980s. “We knew from the start that the Huskies were our arch rivals,” she recalled recently. Accustomed to rowing on lakes and estuaries in the San Francisco Bay area, she marveled at the size of the crowds watching her race in Seattle. “It was wall-to-wall people,” she remembered. “Everyone was yelling so loud you couldn’t even hear the coxswain. We weren’t used to the noise.” The Huskies won that race.

LEGACY

Cruise your boat along the Montlake Cut and you’ll see the old Associated Students of University of Washington (ASUW) Shell House still sitting on the north bank. Now shrouded in trees and bushes, it remains visible from the water and represents an intersection of stories in our region. The Duwamish and other Native peoples paddled their cedar canoes past this point long before the Ship Canal was completed in 1917. During World War I

the US Navy constructed a seaplane hangar in this location, and the vacated building later housed the UW crew and George Pocock’s workshop. It was here that master craftsman Pocock, inspired by Native canoes, designed and built shells from the red cedar found in Washington and British Columbia. After exiting the Ship Canal, turn northward into Lake Washington and you can see the Conibear Shellhouse sitting in the shadow of Husky Stadium. Named for Hiram Conibear, who coached the UW men’s and women’s crew from 1907 to 1917, this structure has served as the center for UW rowing since its construction in 1949. Countless shells have rowed past these sites, continuing a legacy that goes back more than a century.

Today, boaters can be drawn into the crew experience by viewing the slogans that rowers have painted along the walls of the cut over the years. Painting these pithy phrases has become a ritual for the classes of the UW rowing team. Some are inspirational “Speed Ain’t Free 23”; some promote political and social causes, “Believe Women”; some display a competitive spirit, “Let Them Eat Wake”; and some are whimsical, “Full Tilt Boogie.” Many are clever and thought-provoking. They speak to the exuberance, camaraderie, and teamwork that crews have contributed to our region. Rowing past these slogans in my wherry, I feel continuity with the past and our region’s deep connection to water.

SPIRITUAL PURSUIT

Perhaps all sports have a spiritual component, but in rowing it seems especially strong. “What is the spiritual value of rowing?” asked George Pocock, the legendary shell builder who arrived at the UW in 1912. “The losing of self entirely to the cooperative effort of the crew as a whole.” Many descriptions of rowing include the importance of “swing,” the Zen-like feeling that the crew achieves when perfectly synchronized and pulling in unison. “You can have… really strong athletes,” Tom Kellert, a crew coach for Seattle Prep recently commented, “but if they’re not connecting on a deeper level, the boat is not really going to go anywhere” [Chris Egan, “Prep Zone: Seattle Prep Rowers Make History at 2022 Nationals,” Sept. 28, 2022].

Perhaps all sports have a spiritual component, but in rowing it seems especially strong. “What is the spiritual value of rowing?” asked George Pocock, the legendary shell builder who arrived at the UW in 1912. “The losing of self entirely to the cooperative effort of the crew as a whole.” Many descriptions of rowing include the importance of “swing,” the Zen-like feeling that the crew achieves when perfectly synchronized and pulling in unison. “You can have… really strong athletes,” Tom Kellert, a crew coach for Seattle Prep recently commented, “but if they’re not connecting on a deeper level, the boat is not really going to go anywhere” [Chris Egan, “Prep Zone: Seattle Prep Rowers Make History at 2022 Nationals,” Sept. 28, 2022].

My husband Frank, who rowed competitively in the San Francisco Bay area, sees similarities between the rhythms of rowing and sailing with crew. “You have to find a groove,” he explained, “working in sync with each other and with the elements as you move across the water.” The significance of swing, described in the book The Boys in the Boat, also appears in the movie, with the coxswain inspiring the crew to row “as one.” Swing enhances speed and performance while allowing the boat to glide with grace and fluidity.

Lisa Mighetto is a sailor and historian residing in Seattle. She comes from a family of competitive rowers and is grateful to Dianne Willems for sharing her memories of racing in Seattle against the UW crew. For the record, Lisa is a fan of the Husky, not Cal, crew.

For more information, see the Museum of History and Industry’s exhibit “Pulling Together: A Brief History of Rowing in Seattle,” available until June 2, 2024: https://mohai.org/exhibits/pulling-together-a-brief-history-of-rowing-in-seattle/