Part One, told by Chris

When we started the Red Ruby project 18 months ago with Jonathan McKee and Alyosha Strum-Palerm, the Fastnet Race was the top bucket-list race on our radar. Fastnet is well known as the largest offshore race in the world, and this year’s entries topped 460 boats. The doublehanded fleet alone had 106 entries, which was one of the big draws for us. We knew it would be epic, but until the days leading up to the race, we really couldn’t have predicted what that would really mean.

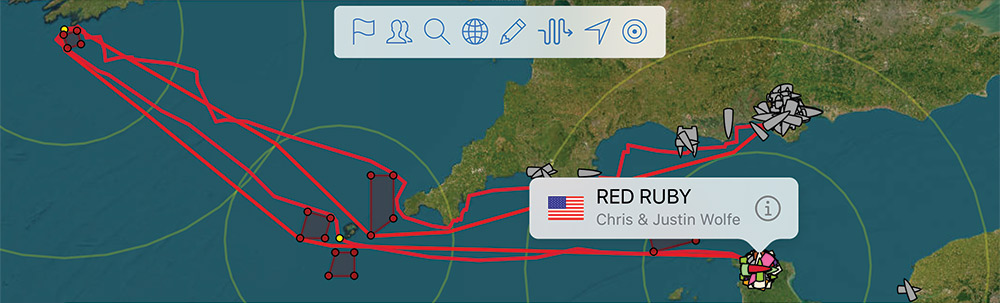

The 690-mile race brings sailors from Cowes, England, on the Solent, west into the Irish Sea, around the notorious lighthouse at Fastnet Rock, then returning east on a similar course, but finishing across the English Channel in Cherbourg, France. The race would be defined by three frontal systems and a relatively short period of light air.

Justin and I have raced on our Jeanneau Sunfast 3300 Red Ruby five times before, mostly in light and moderate conditions. Honestly, we were lacking boat-specific heavy air experience; so, as it became apparent that the start would be in potentially boat-breaking and people-bruising conditions, we refined our race strategy to keep things in one piece and then thought of the “race” as beginning after the first frontal system moved through.

Before the race, we made sure to check all the main reefing systems and get the J4 set up because we have a reefable J3/J4. This meant getting the sail zipped up and jib car positions set. We also chatted with our boat partners about rig settings and strategy for those conditions, and thought hard about other things we might do, like adding some nonskid to deck areas and packing our foulies with easy foods to eat.

We had been thinking a lot about the start and, two days prior, we spent a good amount of time trying to get our timing right and ensuring that we had good pings for the start line. This turned out to be very good preparation, but we were not the only ones with this idea, as we were running the line with the likes of Caro, a Botin 52 that won IRC overall, and Pac 52 Warrior Won, who also ended up on the overall podium.

On race day, getting to the start in 18-25 knots and an increasingly nasty seastate, with an ebb against the prevailing westerly, was a challenge in and of itself. We were constantly avoiding boats and communicating over the sound of wind, waves, and VHF communications from the race committee. They were imploring smaller boats to stay out of the starting area because there was a real chance you would be run over by one of the 100-foot Ultime trimarans that were literally going over 30 knots!

Our start sequence came quickly, and we fell into the pattern that we had practiced over and over again several days prior. I was surprised to feel that we were out in front more than other boats and I thought we might need to be a bit more conservative — had we missed the pings somehow? Justin was not at all worried, though, and he nailed an excellent start, basically on the front row, feet from the line, with no one else ahead of us.

Getting through the Solent was quite difficult. It was all about being very careful to avoid close calls with other boats, ensuring that we made no mistakes with our running backstays that could cause rig issues, and to simply make good, safe decisions. All was going well until I misstepped coming across the cockpit and slammed into one of our seats. The sensation was one I’ve had before when I fell through a hatch and broke two ribs. I was pretty sure I managed to crack a rib on my side, which is better than on my back or front. Adrenaline is a very good thing, though, and it got me through for several hours as we fought the breeze and very short, steep waves.

We opted to stay north exiting the Solent, going through the Hurst Castle route instead of out past the Needles, and were so glad we did. Later, we heard about a SunFast 3600 that sank in the Needles Channel, as well as four dismastings, and saw videos confirming worse conditions on that route than the one we took. We also were in excellent company of other shorthanded sailors we admire and respect — Mzungu!, Bellino, Chilli Pepper, and Tigris — all taking the same route as us.

In our pre-race planning, several major headlands and areas warranted specific attention because of wind and tidal features — Saint Alban’s Ledge, Portland Bill, and then getting through the areas around Land’s End before finally making the launch across the Irish Sea to round Fastnet Rock. We got through Saint Alban’s Ledge reasonably well but it was very bumpy and we saw the biggest breeze of the day there — 38 knots! Thankfully, we managed to round Portland Bill just before the flood tide really started going. The breeze finally started easing slightly after getting by Portland Bill and we opted to go farther north into Lyme Bay hoping for even more tidal relief and calmer seas.

At this point, neither of us was feeling super great. I was in real pain with my rib, and Justin’s normal stomach of steel was failing him. We needed a bit of a reprieve to just take a breather, find ibuprofen, eat and drink, and hit reset. We got across Lyme Bay and then resumed our westerly trek — our northward foray for tidal relief probably didn’t pay as well, but we were feeling marginally better, at least. Our J4 finally came down, and we shook out the reefs in the main, as we transitioned to a much more powered-up mode for the boat.

We got through Land’s End with lots of short tacking along the shoreline and dodging fishing pots — finally some things we were much more used to from the Pacific Northwest! Then, we launched across the Irish Sea and saw the breeze quickly build to 20-25 knots from the second frontal system, which had us close reaching and nearly fetching Fastnet Rock. We had been expecting the breeze to go right, so the correct call was to sail low and fast toward the header.

This part of the race was very long, and very wet, given everything had already been pre-soaked in the Solent. The sailing was relatively easy, though, so it was a great leg to rest and eat, which we did on repeat. We had some issues with our chartplotter, though, as it began malfunctioning from water incursion. It took on a life of its own and was creating thousands of crew overboard waypoints. We left those poor imaginary COBs in our wake. On top of it all, the chartplotter language turned to Polish (we think?) and we subsequently had lots of grimacing fun trying to silence the alarms. Finally, the sunrise came and it was really, really beautiful, the seas flattened out, and we could see the Irish coastline and Fastnet Rock!

Part Two, told by Justin

After a very pleasant close up sail past Fastnet Rock, we were back to sailing upwind in light air past the Fastnet TSS (Traffic Separation Scheme, a no-go box that we couldn’t enter). We’d had a very successful rounding, getting past two doublehanded boats and were now the fourth doublehanded boat on the water. It turns out we are much better upwind in flat water, so it was all good and pleasant.

With the TSS behind us, we pointed Red Ruby across the Irish Sea to the Isles of Scillies. That quickly turned into a very tight reach with our Code Zero. It was interesting to watch how different boats performed on this point of sail. We were holding our position fine for this long, 200 mile reach, but boats were starting to spread out north to south. We kept sailing as close as we could with the Code Zero, not quite making the southern edge of the next TSS near the Scillies. We were expecting a wind shift to make it, but no shift had arrived. We took a quick look at the front of the fleet and realized all of the boats in front of us had already given up trying to get south of the TSS and changed to passing north of the TSS. Keep in mind how amazing it was that after over 400 miles of racing in some extreme conditions, we could still see at least 10 of our doublehanded competitors visually, and twice that on AIS. The racing was so close.

We then had to make a call. Bail and head north, keeping the Code Zero up and praying the shift finally arrived before we had to beat south to get around the Scillies. Or take down the Code Zero and start beating south of the TSS. What tipped the scales for us was that all of our fleet in front of us were headed north. So, north we went, departing from several of our competitors just behind. This was pretty pleasant sailing. Dry, relatively flat seas, and the autopilot had an easy time steering, so we got plenty of rest. We were all topped-up for the final push down the English Channel to the finish in Cherbourg.

As we approached the east side of the TSS and prepared to douse our Code Zero for the beat south and around the Scillies, we had a neat crossing with a French SunFast 3300, like Red Ruby, named Festa 2. We hadn’t been close to them at all during the race. Mostly, they’d been well in front of us, but everyone gave a pleasant wave, acknowledging our sisterships, so close and so late in the game.

Our hopes were dashed a bit when we started heading south, straight at the Scillies. If we had to tack to clear the islands and many, many rocks, we’d get crushed by the boats that went south of the TSS. We could see two of the boats in front of us had already been forced to tack. And then, the shift finally arrived! We were able to ease sheets, reaching with the jib at 7-8 knots straight at Bishop Rock with no need to tack. The gamble had paid! We rounded Bishop Rock, threw up the kite and noted a nice 2-mile gain on the boats that had been hot on our heels, but headed south around the TSS. From here, it was one final 185 mile push downwind to the finish. This was to be our bread and butter.

For us, Fastnet was all about limiting the damage and staying close to the front for the upwind legs, giving us a fighting chance to move up once the spinnakers went up. After an hour or so of rapid gains on the boats in front of us, we realized we had a fighting chance of winning this thing. It was full send on Red Ruby, with incredibly long surfs in the 15 knot range, the miles were clicking by really, really fast. And then the wind shifted and got stronger. Uh oh.

We could no longer hold our spinnaker and make it south of the final TSS on approach to the finish, and it was getting dark and really windy. Despite our competitive spirit, we played it safe and took down the big A2. We took our time getting the A4 spinnaker ready and hoisted. It was a bit humorous at this point — as we were close to shipping traffic heading east in the English Channel as well, we found ourselves catching a tanker that was going 12.5 knots.

The ride with the A4 was right on the edge and we wiped out for the first time ever on Red Ruby. Recovery was straightforward, but with night approaching, we realized our limits and knew we couldn’t fly a spinnaker on a broach reach in this much wind in the dark. So, we put up the J2 jib, took down the spinnaker and started jib reaching the last 85 miles to the finish. We’d passed two boats in our class and we were back to being the fourth doublehanded boat on the water. Two boats in front of us were in sight on AIS, roughly 6-8 miles away. They also appeared to be totally comfortable with the conditions and at least one of the two kept their spinnaker up all the way to the finish.

That last 85 miles was in complete darkness. It was raining and impossible to tell the sea from the sky, nevermind that we passed a 65-foot race boat just to our north but never actually saw any visual evidence they were close by. It was so dark. Lucky for us, our autopilot worked flawlessly for this night-time blast reach. Several others were not so lucky and had to hand steer, essentially blind-folded. The autopilot gave each of us an opportunity to take turns staying down below, resting, and avoiding the not-so-warm fire hose of water on deck. The crazy thing is that our speed didn’t drop when we switched from the kite to the jib. In fact, we recorded our top speed ever on Red Ruby in this configuration — 20 knots! In the blackness, with the autopilot driving and just the main and jib, it was a wild, wild ride. To hammer home the point, we blasted across the finish line in Cherbourg just 3 miles behind the second and third doublehanded boats. Despite them carrying their spinnakers through the night, we gained several miles on them. Wow.

And we’d done it. We’d finished the Fastnet! Perhaps the most famous, definitely the largest, and often one of the most difficult offshore races in the world. From the sailors we’d talked to that had done many Fastnets, this was the toughest one they’d experienced. Three low pressure systems swept across the course during our race, and a highlight for us was that we used every sail on the boat and needed no sail repairs at the end. That had to be a minority outcome after the conditions we saw throughout the race. At the finish, Red Ruby was 100% ready to keep racing. We, on the other hand, were ready for a beer, a shower, and a long nap!

Overall, we sailed a good race, executed our plans, and while we, of course, made mistakes on the course, we don’t think any of them cost us much. We left it all out there and had no regrets.

That effort netted us fourth overall in IRC 2 out of 98 boats, and seventh overall in IRC Two Handed out of 106 boats. Perhaps the best part: Chris won the award for first-place female skipper in the entire Fastnet IRC fleet!

It was an incredibly tough race, but this one is going to give us many lasting and wonderful memories. Maybe that is why we do this? It’s not so much the experience, but the treasured memories we get to keep with us for the rest of our lives.

Thank you, every one of you, for your warm support. We appreciate you all.