When 48° North asked new Southern Straits Regatta Chair, Peter Salusbury, if he could think of an interesting story to share about the classic event, he said, “Hmm, hard to say… I’ve done 48 of them.” That’ll do, Peter, that’ll do!

In 1970 at the age of 15, I was invited to race in my first Southern Straits Race on a newly launched Newport 27 with some neighborhood friends. The classic distance race had been started by West Vancouver Yacht Club only one year earlier. Little did I know that experience would forever change my Easter weekends. With 53 years and 48 completed “Straits Races” in my wake as either skipper or crew, it’s impossible not to reflect and ask the proverbial question, “What makes this race so special?” Here are my personal reflections on over five decades of Straits Races.

1970 to 1979: The Early Epic Years

The 1970s era of Straits Races frequently featured epic adventures, and this seemed to be especially true for the 27-30 foot boats I was racing on as foredeck crew. Easter weekend was typically blustery, cold, and rough. At this time, the only course offered was a long course averaging about 125 nautical miles. Because of the distance and the speed of boats in that era, it was common to have the time limit set at 50 hours and, in 1974 sailing on the C&C 27 Vatican, we needed every bit of that time, finishing in the afternoon on Easter Sunday after starting on Friday morning. Food rationing was in full effect as our race extended past two days in duration. It’s funny to think that today we complain the race is too slow if we finish after midday on Saturday.

It was also an era in which “old school” coastal navigation skills were required (it was long before Loran C or GPS) using hand bearing compasses, radio direction finders, and keeping running plots. In 1976, I had the chance to do navigation and foredeck on a new Peterson 35 Pearce Arrow. I remember using the Radio Direction Finder (RDF) most of the night to calculate our position and keep a running plot as we sailed from Sisters down to Entrance Island in reduced visibility and a stiff southeasterly breeze. It’s interesting to reflect on how much tougher navigation was back then compared to today’s GPS plotters and smartphone apps. We had a crack crew of Olympic sailors aboard and Pearce Arrow got the overall win that year.

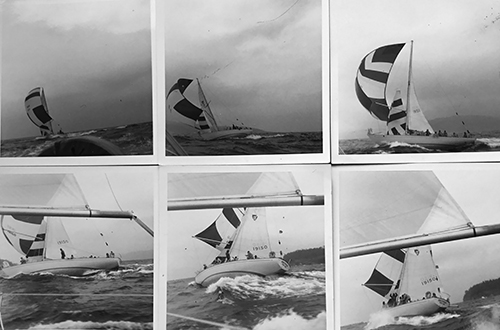

The other characteristic of the 1970s was all the IOR-optimized boats with tall, skinny aluminum masts and stainless steel wire standing rigging. Because of this, dismastings were not unusual in Straits Races. In 1977, we were beating back from Ballenas Island on the last leg aboard Pearce Arrow when the cap shroud broke just as we were about to tack off the Worlecombe Island shore and suddenly the mast and sails were in the water. After calling “Mayday” we tried starting the engine, but the start button had been pushed into the lazarette, which was inaccessible — so no engine. By the time our competitors recognized we needed assistance, we were too close to the surf line and eventually we pounded up against a rocky ledge of the island. One by one, we took turns timing the violent pounding on the rocks and leapt off on to the rocky ledge. Eventually we all got off safely and then the rising tide picked up the boat on a wave and smashed it up on the ledge where we all had just been standing. As the tide came up during the day, the boat continued to wash farther up onto what was now a rocky beach. I still remember starting a campfire and cooking oysters as we stripped the boat of anything valuable. Fortunately, that night on a high tide, we were able to salvage the boat by pulling it off the beach, placing high volume bilge pumps inside and towing it to Fisherman’s Cove.

And because lightning sometimes strikes twice, I enjoyed another dismasting the following year aboard the 41-foot Kanata, this time running downwind in a big breeze off Lasqueti Island. The hydraulic backstay adjuster broke, dumping the rig, full main, spinnaker, and jib over the side. Luckily, we were able to get the rig back up on deck, no one was hurt and we limped into False Bay for the night. Even after back-to-back dismastings, I kept coming back for more!

1980 to 1989: Short Course, Sail Changes & Technological Advances

During the ‘80s, a short course was added to Southern Straits Race to reduce the suffering of smaller, slower boats. The short course became a big success, allowing smaller boats to complete the roughly 50 mile course in a manageable time.

The 1980s were also characterized by the emergence of more available and affordable electronic navigation, in the form of Loran C. It was a steep learning curve for us all and not without some memorable experiences. Racing on the Peterson 35 Arluk in the 1983 race, the owner I was sailing with — who was a technology guru from Alberta — proudly came on deck to inform us that his prized Loran C had given us a confirmed position in the middle of the runway of Vancouver airport! Needless to say, these races required navigators to continue practicing the art the old-fashioned way using hand bearing compasses and radio direction finders.

During the races in the ‘80s, we had to carry an almost absurd number of jibs, spinnakers, and bloopers to be competitive in IOR. It wasn’t unusual for competitive one-tonners and two-tonners to carry 15 or more sails, which kept the foredeck crew hopping as it seemed that for every 5-knot change in wind speed, we had to peel a jib or spinnaker. On Arluk, we did our best to reduce the number of spinnaker peels by blowing out two spinnakers in a strengthening southeasterly right after the start and before we had left English Bay, and then badly burning a third spinnaker the following morning while making breakfast. That was one way to keep the foredeck workload down, but the owner was not impressed.

1990 to 1999: Inshore Course, Emergence of Light-Displacement Flyers

In the 1990s, a one-day inshore course was also added to long and short course options, allowing smaller boats who didn’t want to race overnight participate in the event. This inshore course has since become a staple for the Straits Race and has been a big draw in recent years for the smaller sport boats like the Melges 24s and Vipers.

Though almost all of my Straits Races have been on the long course, in 1993 and 1994 I had the chance to sail the short course with Doug Race on his meticulously prepared Hotfoot 30 Ballenas, where we proudly took Line Honors in 1993 and divisional wins both years.

The 1990s also saw the emergence of the light displacement flyers, most notably Jonathan McKee’s Riptide 35 Ripple, the Santa Cruz 50 Delicate Balance, the Nelson Marek 36 Surface Tension, the SR33 Ballenas, Sandy Huntingford’s General Hospital, and the NM 40 Occam’s Razor.

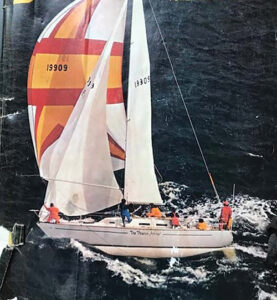

For me, the 1996 race was most memorable, as we started in a light-but-building southeasterly breeze. I was sailing with Doug Race on his new SR33 Ballenas, which was a relatively light displacement downwind flyer, and we enjoyed a very fast downwind leg to Sisters hitting boat speeds in the high teens for the first time in our lives. But the star of that race was McKee’s Ripple, which was much faster downwind and was the second boat in the fleet around Sisters behind the maxi Cassiopeia. I’ll never forget watching them rocketing upwind with the water ballast in play on the way back. Many years later, that performance by Ripple inspired me to work with Paul Bieker and Jim Betts to create my own version of the Riptide 35 concept, which became Longboard.

My other lasting memory of that 1996 race was the long beat back from Sisters in southeasterly that had by then risen above 25 knots on our way to the T10 mark off the Vancouver airport. There was a brief jib reach from Halibut Bank to White Islets where we had planned to put a kettle on to get some warm drinks in the crew, but the SR33 was so fast on the reach that the leg was finished before we knew it. By the time we got to T10, two-time Olympian Penny Stamper and I were the only two people left on deck, trading off helming and playing the main. Penny was the sweetest, nicest person in the world who never lost her cool, but just as we were about to round T10, she turned to me and yelled, “Upwind sucks!” In the end, it was all worth it as Ballenas took the division win.

2000 to 2009: Medium Course, Technology Advancements

The aughts decade saw an ever-higher proportion of lightweight boats and, with improvements in rigging and more carbon masts, dismastings became thankfully rare. Navigation got much easier with the ubiquity of GPS, but was still not without some technical glitches.

My GPS ‘glitch’ memory from that decade was in the 2009 race aboard Peter McCarthy’s 1D35 The Shadow. We rounded Sisters Islets in a fresh southeasterly and decided to short tack up the Vancouver Island shore to get out of the larger waves and look for the southerly shift in wind direction which sometimes occurs. We had a fancy new race tablet in the cockpit connected wirelessly to the onboard GPS receiver, so we were confident we could navigate our way through the Winchelsea Islands safely — what could go wrong? Wouldn’t you know it, as we started to thread our way through the islands, the tablet died along with the GPS signal. It was getting dark and we were somewhat committed to carry on, so out came the paper charts and hand bearing compass.

We managed to safely work our way down that shore, picking up the southerly shift, and went on for the overall win on the 100-mile medium course (which had been added to the race offerings in 2007 to accommodate faster 30-35 foot boats). It may have been almost a decade into the new millennium, but here was one more example of never relying on any one piece of navigation equipment, and those traditional navigation skills really came in handy.

2010 to 2023: Safety Focus, Best Straits Race Ever

The famous 2010 Straits Race became a defining moment in the Pacific Northwest, with all overnight races placing a significant new focus on safety at sea. 2010 was the year that storm force conditions hit the race course forcing the race to be abandoned in the interests of participant safety. Two boats were dismasted, and the custom Clint Currie designed 30-foot Incisor was swamped with all six crew rescued, but suffering from hypothermia. Following the race, debrief sessions were held and lessons learned were developed. These takeaways have improved the safety culture of distance racing throughout the region, the Straits Race very much included. Most notably, the Safety at Sea program was developed in British Columbia and the two-day Offshore Personal Survival Course (OPSC) has been delivered multiple times per year in British Columbia since 2011. The demand from the racing community for the OPSC and the one-day Coastal Personal Survival Course (CPSC) sessions is high, with all sessions selling out quickly.

From my perspective, most of the Straits Races since 2011 have had generally pleasant conditions, with the 2015 race being a noteworthy standout. We always dreamed of a Straits Race where we would start in a medium-to-strong southeasterly breeze to carry us to Sisters Islets, and then the wind would miraculously switch around to a nice steady northwesterly. Well, in 2015 that happened for the long course! The northwesterly came in just before Sisters, but we only had a light one-mile beat before rounding Sisters and relaunching the kite for a beautiful afternoon and evening downwind sail. It was a magical night with a lunar eclipse, shooting stars, and a rare “moonbow” from one of the brightest moons I’d ever experienced in Straits Race history. The predominately downwind and reaching conditions really favored us on Longboard and we proudly earned the overall win on the long course. It was definitely one of my favorite Straits Race memories.

What Makes Southern Straits So Special

While these are my memories of how the race has changed over the decades since its inception in 1969, there are so many attributes of the Southern Straits Race that have truly stood the test of time. Which brings me back to the question, “What makes this race so special?”

One of the special aspects of the race is that it’s the first overnight race of the season, so it’s great to get the crew together after the winter break to work through the job jar on the boat, get out practicing, and set the boat up for the race. There’s that start of the season excitement as we plan for the race and look forward to what is always a new adventure to enjoy together.

The other part of it being the first overnight race of the season is reconnecting with old friends from around the region, most of whom we haven’t seen since the previous race season. The pre-race dinner and skipper’s meeting at the clubhouse on the night before the race is always a reunion of sorts, filled with laughter and friendly banter — exchanging hopes and expectations for the coming days, as well as recounting Straits Race adventures of the past.

And then start day arrives and we hope for one of those magical races with either a fast downwind slide on a southeaster to Sisters Island, a warm Qualicum outflow wind during the night off the Winchelsea Islands, or a moonlit downwind sail home on a northwesterly… or all of the above like in 2015! On those special weekends when the sky is clear and cool, the scenery of the Strait of Georgia is unmatched, with snow capped mountains and potential encounters with the local whale pods. Experiencing the incredible beauty of the British Columbia coast has always been a major draw of the Southern Straits Race.

Lastly, one of the reasons that makes me come back each year is simply taking on the challenges of an Easter weekend race, whatever weather conditions it throws at us, adapting to those challenges as a crew, and doing the best you can under the circumstances. Winning the race may be the primary objective, but I can recall many years when simply finishing the race and having fun with a great bunch of people was the lasting reward, no matter what the result. Whether it’s remembering a funny onboard story or overcoming the challenges of a wet and windy night, the Southern Straits Race has always been a personally rewarding event producing friendships that last a lifetime and memories that will never be forgotten.

I’d like to thank the literally thousands of volunteers at my home club (and host of the Southern Straits Race), West Vancouver Yacht Club, who have contributed to the success and legacy of this important and remarkable event. The sense of community and commitment the club brings to this race is a hallmark of the culture at West Vancouver Yacht Club, something which all Straits Race participants benefit from.

Peter Salusbury is the owner of the Riptide 35, Longboard, and is the regatta chair for WVYC’s Southern Strait Race.

Feature photo by Lin Parks.