When three crew members from the same boat went overboard during the Blakely Rock Benefit Race, the J/105 Avalanche responded. Here is their story and takeaways from the incident.

On the return leg of the Sloop Tavern Yacht Club’s Blakely Rock Benefit Race under spinnaker on the J/105 Avalanche on April 1, 2023, we heard a “Mayday” call on VHF channel 16. We decided to fold our sails and respond to the call. We backtracked towards an area where we had seen several boats broaching and quickly found three boats milling around a crew overboard (COB).

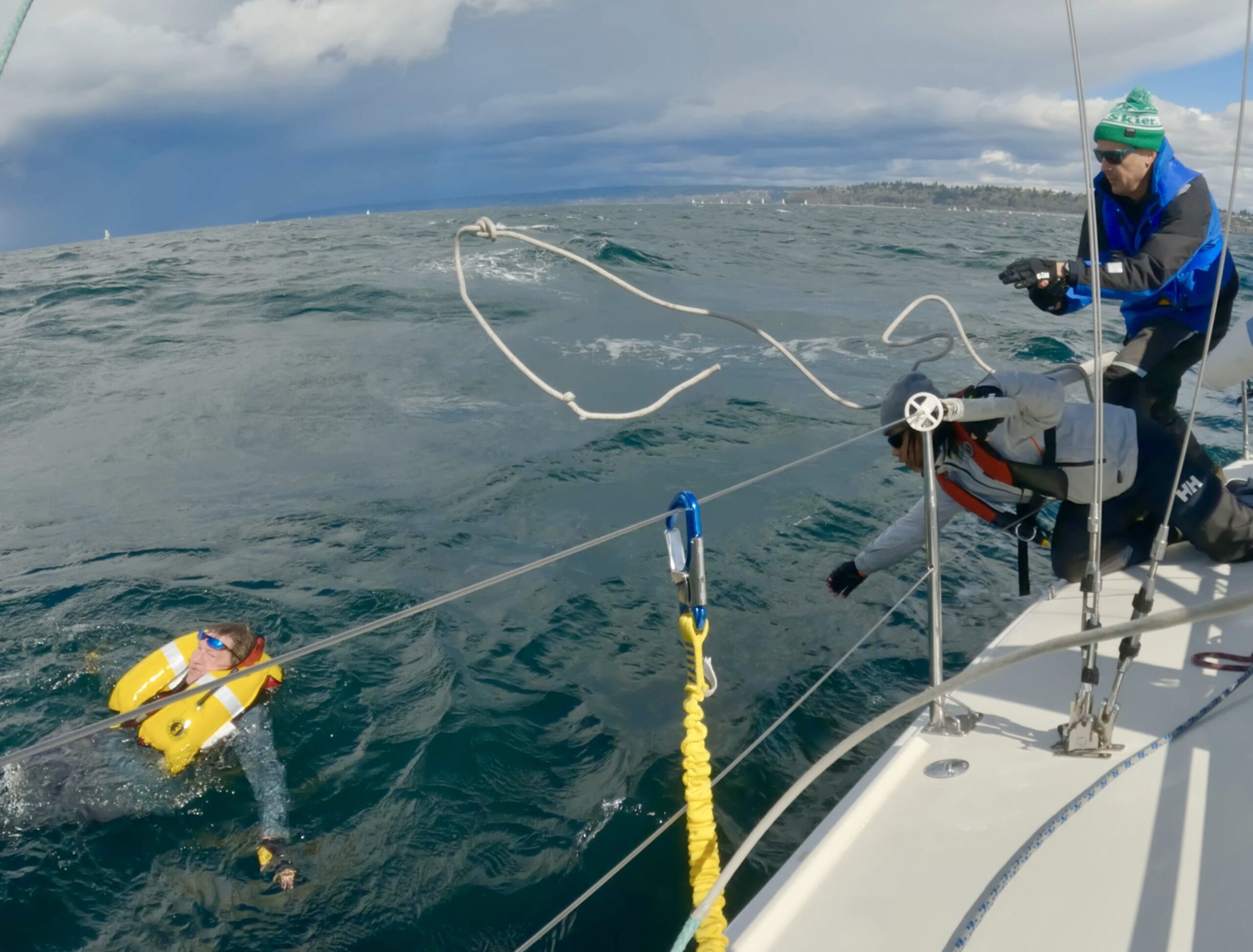

After making sure that our arrival was not interfering with another pickup attempt, we quickly reached the first COB from an upwind position, threw a line, and pulled him over the rail. He was strong and we had one strong crew to help. This would have failed with a weaker person, and we do not recommend this method as both our crew and the COB were super exhausted after this effort.

We then saw another COB in the water that we approached similarly, threw a line and then dragged him carefully to the transom where he was able to get up by himself on the ladder. This was the better way.

The two sailors brought on board mentioned that there was a third person in the water. We did a quick sweep and spotted her. As she looked unresponsive, we decided to use a different approach. We went upwind of her, then let the boat drift down until she was against the hull. Leaning under the lifeline, we grabbed her hard and looped a line under the suspender of her life jacket. Another crew walked the spinnaker halyard to her level and the crew already leaning down snapped the shackle to the rings on her life jacket. It was time to winch hard on the halyard to hoist her over the lifeline, swing her above to the companionway and lower her straight into the cabin. There, one of our crew and the previously rescued crew members attended to her by removing wet clothes and layering everything on hand from spare sweaters and flannel shirts to sail covers to keep her warm.

We radioed on channel 16 that we had all three COBs on board, two in seemingly good shape and a third one hypothermic with totally limp muscles and no speech. The Seattle Fire Department, who heeded the original Mayday call, already had a boat on the way, which rafted to us halfway to Shilshole Bay Marina. Three firefighters came on board and brought blankets, and were ready to bring resuscitation equipment if necessary. We proceeded quickly to the marina where three ambulances were on standby. The rescue was over for us with questions remaining. How did the three sailors fall overboard? Would they recover?

All three crew members that went in the water were from the same boat and were in the same family: a father in his early 60s, with a daughter and a son in their 30s. They broached as they were taking their spinnaker down and the daughter, who was working the bow, fell overboard. Her brother lost his footing throwing the LifeSling and went overboard. The dad went over when he managed to grab his daughter’s hand, and then lost his grip and footing as a wave rolled the boat. These facts, not immediately evident the day of the event, came to light in an exchange of emails between rescuers and rescued trisome, in the course of the following week. That communication was soothing for both sides. The woman who was hypothermic was treated at a hospital, but came to the after regatta award party for a brief time. It was good to see her walking and talking. She was very tired but in good spirits. She said her body temperature was at 92° when the hospital admitted her and 99° when released after five hours under electric blankets and an IV. Any body temperature under 95° is considered hypothermic and life threatening.

“I remember being in the water and then waking up in the ambulance. I don’t remember being on your boat,” was her next sentence, which shows how close to the edge she had been.

After significant communication with all three COB we recovered, here are some perspectives and takeaways from those who had gone in the water, as well as from those aboard our vessel enacting the rescue.

Lessons from the victim side:

- Stress can easily make a tricky situation worse. In such instances, think hard, tether yourself, and avoid rush moves.

- If a crew falls in, do not attempt an athletic throw of the LifeSling that can send you overboard. Steadily position yourself and then throw the LifeSling a nominal distance of 15 feet or whatever you can easily control. If you miss, drive in a circular motion to get the end of the LifeSling to come close to the COB or do a new approach depending on what is easiest in the given waves and current.

- If your hand meets the COB, wedge yourself against the stanchions low on the deck so there is less of a possibility to topple over the side. Talk to the person at the helm to get the engine power at the correct level and direction to minimize drag. Have another crew quickly replace your hand with any line on hand. Proceed to hoist with a halyard as described.

- Note that all COBs had adequate life jackets that were deployed properly (editor’s note: the woman COB’s life jacket didn’t have a crotch/leg strap, which made its fit and function less ideal). All on board had been shown how to use the VHF. The situation would have been worse otherwise.

Lessons from the rescue crew:

- With winds gusting at 28 knots, choppy 3-foot waves, and current of 0.7 knots, it was hard to keep contact with the COB for more than a fleeting moment. A good approach slightly upwind with the right speed was key. Keeping the boat parallel to the waves and letting the waves push the boat to the COB worked.

- Lines must be ready to be thrown quickly before the current sweeps the COB away. In waves and wind, the boat and the COB drift at vastly different speeds. Once the line is secured the COB must be carefully dragged to the transom if equipped with a stern ladder. If the waves are too big to use the ladder, which then swings up and down out of control, resort to using a halyard as done in the third COB rescue that day.

- Do not throw the halyard at the COB. It is hard to grab as it swings wide with the possibility of getting stuck high and out of reach. Throw a line of sufficient diameter that can be grabbed easily. Secure that line under the suspender of the COB by pulling them against the hull while you lie flat on deck wedged against the stanchions. Pull the victim to the side of the boat at the level of the companionway. Hook the halyard on their belt and proceed as described in this rescue. Each rescue is different so be prepared to improvise. Stay calm and coordinated listening to one voice.

- Call for ambulances at the marina to get medical attention, even if your COBs appear relatively fine. If the water is cold, as it is in Puget Sound, they are in shock and need attention. Accept help from professional rescuers even if this implies a rafting situation that can cause damage in waves. We had bent stanchions on Avalanche — a small price to pay. Every minute counts in fighting against the cold. The water was 46° that day, and our severely hypothermic COB had been in the water for 25 minutes by the time she was brought aboard. It does not take long to be in trouble, even dressed in three layers.

- If your LifeSling has a block and tackle arrangement do not take time to organize them. On a sailboat, a halyard makes a better hoisting device if of sufficient length. If necessary, extend it with a simple line or a portion of the LifeSling . LifeSlings — while great and indispensable in certain situations, particularly with COBs not wearing a good life jacket with harness — are not the only device for a rescue and may not be the fastest tool. Think LifeSling combined with a halyard at times when you want the benefit of the long line and the padded U piece on the end. Also, have a 20-plus foot dock line ready to throw. This can be your primary device or a good complement, depending on the situation.

- Above 15 knots, tether yourself, particularly under a spinnaker when broaches are possible. Jacklines allowing you to move along the side of the boat with your tether always hooked are a safe addition.

- If you hear a Mayday call, respond. With many boats around in a regatta situation, we almost did not respond because we were not direct witnesses and other boats were closer. We knew the local rescue authority had already dispatched a specialized unit. This unit took another 20 minutes to arrive after our first pick-up and 10 minutes after our last one. This extra time might have had grave consequences for the woman in advanced stages of hypothermia, and a worse outcome for the gentlemen picked up earlier. On the other hand, our worst outcome of exiting the race to respond and arriving “after the battle” is the loss of an entry fee, not loss of life. When a COB occurs, make yourself available, just in case! Forget about being on the podium that day or your post-race appointment(s).

- We had three-foot waves in the relatively protected Puget Sound. In larger waves or winds above 30 knots, use the same principles but expect to work a lot harder to retrieve the COBs. Be methodical and expect multiple passes. Success is not a given, so get as much help as your distance from shore permits.

Written by Jean-Pierre Boespflug, on behalf of the crew of the 34.5-foot J/105 Avalanche on the day of the rescue — Frederic Pergola, Jayson Stemmler, Thomas Han, Kale Buonerba, and Jean-Pierre Boespflug.