For more than 10 years, our 40-foot pilothouse trawler Mischief has been both our comfortable home-away-from-home and our magic carpet to new places. My wife Karen and I especially love beautiful scenery and opportunities to anchor all alone. Being beyond signs of civilization is always a plus. This year, we decided on a late summer cruise to the waters beyond Nakwakto Rapids in British Columbia.

We left Seattle on August 10 and traveled at a leisurely pace through the San Juans, Gulf Islands, Desolation Sound, Discovery Islands, and the Broughton Archipelago to arrive at the starting point of our Nakwakto adventure — Allison Harbour — on Sunday, August 28. It proceeded to rain all afternoon, evening, and night. We never left the boat. It was an unceremonious start to what would be a stunning cruising experience in a little-known corner of the Inside Passage. In the morning, the rain had morphed to low clouds, so we were off to go the 5 miles or so to Nakwakto Rapids.

Nakwakto Rapids is one of the strongest tidal currents in the world, and is the intimidating gateway to beautiful Seymour and Belize inlets. Access to Nakwakto — which is located just northwest of the Broughtons, only about 15 miles from Cape Caution — and the waters beyond requires attentive navigation through a sea of rocks and islands, whether you approach from the east (Schooner Channel) or west side (Slingsby Channel) of Brahman Island. Getting there is only the first step, however. Ebb currents can reach 16 knots, and the morning’s prediction had it pegged at over 11 knots for our transit — nothing to trifle with. We wanted to reach the rapids exactly at slack, 12:01 p.m., and left Allison Harbour with plenty of time to adjust our speed to get the timing exactly right. On the approach to the rapids, we sighted a lone sea otter — the first we had seen on this part of the coast. As it turned out, we were 4 minutes early; but it didn’t matter, it was perfectly calm with only a half knot of current left in the ebb.

One feature that makes Nakwakto so dangerous is the turbulence caused by a small island called Turret Rock right in the middle of the narrowest spot. It is said that on large tides the rock actually trembles at full flow. Over the years, boaters have taken their small, high powered dinghies to the rock at slack and posted a sign with their boat names on a tree. Since our dinghy is human powered, we took a pass.

After transiting Nakwakto, we entered Seymour and Belize inlets — 220 miles of fjords reaching into the Coast range of British Columbia. This is one of the most remote and least visited areas along this stretch of coast; the first nautical chart of the inlets wasn’t issued until 1987. Even now, it is not often traveled by cruisers and we didn’t expect to see another pleasure boat.

We anchored our first night in a corner of Westerman Bay, a deep cove stretching north as you head up Belize Inlet. Except for the usual evening breeze, it was almost totally calm. It’s about 20 feet deep and the bottom is covered with eel grass, which is good crab habitat. We put out a pot first thing. Then we rowed around looking for feathers floating on the surface of the water for Karen to add to her collection. We also identified six different small streams entering this part of the bay, no doubt the result of the previous day’s rain.

On the first morning we awoke in Belize Inlet, the weather improved, as mostly cloudy skies gave way to occasional sun spots and finally to bright sun and blue sky with occasional puffy white clouds. It was a perfect day for our trip to Alison Sound. We pulled in our crab trap and examined our finds: two starfish and one moon jelly — not the fruitful catch we had hoped for.

It’s about 25 miles from Westerman to the head of Alison Sound, mostly traveling eastward towards the mountains, first up Belize Inlet before turning north into Alison Sound at about the halfway point. Along the way there were a number of waterfalls, including a spectacular one from Trevor Lake that dropped right into the Inlet. You can practically drive the boat right up to it; the water is so deep.

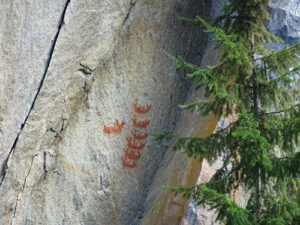

While the name “Sound” might suggest a large body of water, in these parts it is often used for a narrow, steep-sided inlet that flows into a larger inlet. Alison Sound certainly qualifies. It averages a third of a mile wide through its 11 mile length with mountains on both sides rising three to four thousand feet right out of the water — in many cases as spectacular rock walls. It is also deep — too deep for anchoring except in a few isolated places and even then it’s deep. We traveled slowly up the Sound, checking out the anchorage possibilities and the cliff faces for pictographs left by First Nations peoples from 150 or 200 years ago. We found one depicting a long boat with a number of oars and six native canoes, probably from the mid 19th century.

When we got to the head of the Sound the water was dead calm, the sun was shining and there was a welcoming committee in the form of a small black bear on the beach.

The heads of most of the inlets on this coast are marked by a river delta that drops off into deep water very quickly. One minute it’s 200 feet deep then, before you know it, you’ve run aground. But in some of these deltas there is a narrow band where you can drop an anchor and still have room to swing before hitting shallow water. We dropped our anchor in 90 feet, let out 240 feet of chain, and backed up to stretch out the rode. The depth was 15 feet when the anchor was set and we were still a couple of hundred yards from the beach. But it was glassy calm and we felt perfectly safe. It was a spectacular place to spend the night, surrounded by pristine wilderness with the closest humans being a long way away.

The stars were brilliant in the middle of the night. By morning, fog had rolled into the Sound and only our boat and the edge of the shore around us had escaped the cloak of zero visibility. The rising sun slowly lit up the scene, first on the tops of the snowy peaks, then the hillsides, and finally our little bay, gradually driving the fog away. We watched this process for several hours while rousing ourselves from slumber, eating breakfast and getting the boat ready to go. By this time, the fog had lifted to form a layer higher than the water and lower than the mountain tops, so we got underway. The water was still as calm as it had been the day before and during the night.

At the northwest corner of Alison Sound and Belize Inlet we found another pictograph and, after getting a close-up look, we entered Belize Inlet for the journey back the way we came. The winds tend to follow these long inlets and we faced a 10 knot breeze that raised a substantial chop all the way to the junction with Seymour Inlet. When we turned the corner into Seymour, it became calm.

We continued up Seymour for a few miles to Charlotte Bay, which is a nice anchorage, open to the northwest with the potential of a good sunset view because the land around it is quite low, much different from the mountains of Belize Inlet. And the temperature was decidedly cool — 65 degrees after the previous day’s 81. Conditions certainly change quickly at this time of year.

On this first day in Seymour Inlet, we actually saw other vessels — all work boats in one form or another. A small tug was towing a log boom, a high speed aluminum crew boat buzzed around between various logging camps, a landing craft was traveling somewhere, but there were no other pleasure boats. We weren’t alone anymore, but it certainly wasn’t crowded.

Shortly before sunset that evening, the fog rolled in once again; and was still lingering in the morning. Fortunately, it wasn’t all that dense, visibility was a quarter mile at least, so we decided to continue our journey towards the head of Seymour Inlet. Other than one narrow spot filled with islands where the inlet makes a slight jog, Seymour is wide and deep with no hazards. We navigated with chartplotter and radar and, after about an hour of travel, the fog had lifted to about 200 feet above the water. Visibility was fine at water level, we just had no view of the mountains. The water was smooth as glass. As we motored the inlet kept getting deeper until our depth sounder stopped reading at 1,966 feet.

The farther you travel up the inlet, the higher the surrounding mountains become and we wanted to see them. Since it was lunchtime, we decided to stop and wait for the fog to lift. We could have just stopped in the middle of the inlet and drifted, but just at that moment we happened to be passing the only anchorage for miles around. It was a little one-boat nook called Jesus Pocket, so we pulled in and dropped anchor. The sun came out and there was even a small stream to listen to as we ate cucumber sandwiches in the cockpit. Sweet.

Our lunch break ended just as the fog finally dissipated completely so we continued our journey to Frederick Sound, the southeast-reaching fork of Seymour. Starting with Eclipse Narrows, it continues straight for a few miles before narrowing and following a set of U-turns amongst steep, 2,000 foot high peaks, ending in a bay with black cliffs above — our home for the night. Anchoring depth was modest at 60 feet with room to swing.

At this point, we were only 3 miles, as the crow flies, to Mackenzie Sound in the Broughtons, an 80 mile journey by boat. It turns out this is the site of a former logging operation that was abandoned not too long ago and, most usefully for us, there was a logging road heading up through the trees toward Mackenzie. A hike at last! We rowed to the dock and hiked up the road about a mile to the first major blow down before turning around. It was a nice hike with gentians flowering in the road. We would have gone farther, but it was late in the day and we had to keep stepping around large piles of bear poop as we walked, some quite recent. Remembering how far we were from help, we decided to play it safe and head back to the boat.

With a little wind and fog, the morning wasn’t as picture perfect as the night before had been. But we were in no hurry and had a delightful breakfast — Karen’s orange cranberry bread — and still managed to get a fairly early start. As soon as we left Frederick Sound and re-entered Seymour Inlet, the wind fell to zero, the water was flat calm, and the fog dissipated.

When we got back out to the jog in Seymour Inlet that we had navigated in the fog the day before, we investigated a couple of potential anchor sites, each useful in different wind conditions. Then we headed south into what one of our cruising guides called Explorer Inlet, but is unnamed on the chart. It eventually leads to Nenahlmai Lagoon but three miles down, it narrows and becomes so shallow that our boat could only go through on a very high tide. Luckily, just before the narrows, the Passage widens into a lovely bay suitable for anchoring, so we did. It was very calm and would have become hot in the boat were it not for the increasing clouds. That, and the falling barometer, showed a change in the weather was in the works. In the meantime, we enjoyed a great sunset with many layers of clouds.

Our penultimate day beyond Nakwakto Rapids started with a clear sky and brilliant view of Orion to the southeast and Jupiter to the southwest. That was at 4 a.m. and, by the time we got out of bed, it was cloudy. Soon, showers began and the rain got heavier around noon. It was not exactly an auspicious start to the day, so we decided to stay where we were for another night. The barometer had been steady and there was no wind so we were hopeful for good weather the following day.

Mischief is both a very seaworthy cruising boat and a comfortable living accommodation, and it was a good day to enjoy the living aboard part of boating to the fullest. That meant a mixture of boat chores, food, music, writing, and art — maybe even a nap. Life is good on a boat, even in the rain; and it’s even better in beautiful and remote locations.

The wind and hard rain continued until 2 or 3 in the morning. Not long after, we woke up thinking the boat had dragged its anchor and was being carried away by the rapids; the sound of rushing water was so loud. But a look around in the intense blackness somehow convinced us we hadn’t moved. In the morning we could see the source of the sound — we had managed to anchor 100 yards from three waterfalls coming down the steep hillside next to us, which hadn’t existed the day before. It’s amazing what one rainstorm can do.

We spent a week exploring beyond Nakwakto Rapids and, true to our expectations, the scenery was spectacular and we never saw another pleasure boat. As we readied ourselves for life back outside Nakwakto, we found the rapids calm at our targeted 11 a.m. slack. We continued back through Schooner Channel the way we had come a week before. Amazingly, we saw the same sea otter in the channel but it was still too shy to pose for a picture. When we re-entered Queen Charlotte Strait the wind was light with a low swell from the ocean and we could finally hear chatter on the VHF again. We continued on towards Vancouver Island, which, at this point, was only 9 miles away. Our exploration beyond Nakwakto Rapids was over for this year.

Michael and Karen have been cruising the Salish Sea and beyond for more than 20 years, the last 10 aboard Mischief, a 40 foot Eagle pilothouse trawler with all the comforts of home. Karen is a former Art Director for 48° North. Photos by Karen Johnson.