Sailing a small boat is like moving a paintbrush across the water. It’s slow, thoughtful, and requires a careful, continuous attention to detail. A typical cruising day for me covers just 10 to 15 nautical miles. On a pretty good run I might pass the 20-mile mark, and a 30-mile day is epic.

Sailing a small boat is like moving a paintbrush across the water. It’s slow, thoughtful, and requires a careful, continuous attention to detail. A typical cruising day for me covers just 10 to 15 nautical miles. On a pretty good run I might pass the 20-mile mark, and a 30-mile day is epic.

Despite the slow pace, there’s not much time to do anything but mind the tiller, control the sheets, and feed myself. Even a slight lack of attention will cause my craft to veer off course, round up, or worse. Yet I am able to scan for danger, watch the weather, and steer, while another part of my mind observes things that have nothing to do with survival at all: the fin of a lone harbor porpoise as it comes up for air; tiny bryozoans encrusting a blade of eelgrass; the profound fog rising beyond a headland. Moving slowly, I spot so many stimulating things around me that I want to capture them all.

When I’m able to stop, a camera seems a decent tool for the job, and it certainly has its place in my gear. But too often, fiddling with knobs or reviewing a photo takes me out of the scene. Besides, it’s easy to capture too much with a digital camera. I often rush to get the next shot, without considering how well I’ve framed it, or whether I’d truly wish to revisit the scene later. Heck, beyond the first couple of days after a trip, does anyone ever sit down and pore over their collection of digital photos?

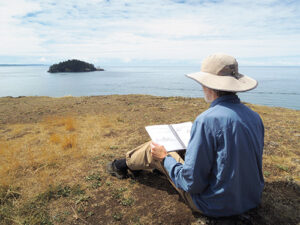

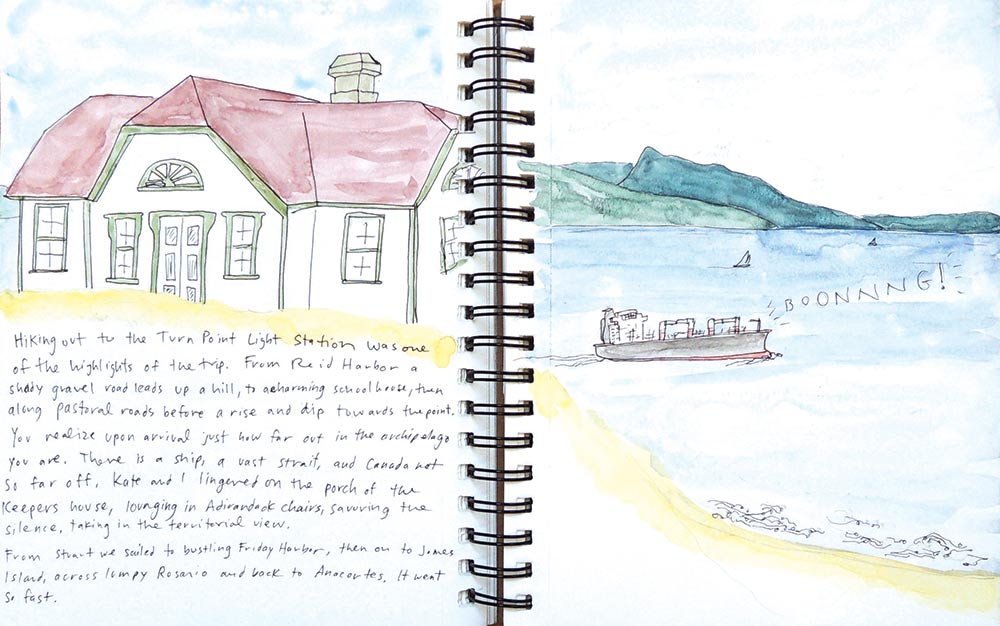

In the last few years, I’ve found something that works better. Drawing satisfies my desire to record both little details and broader landscapes. So on a cruise, in addition to my ship’s log, I always carry a sketchbook, pencils, waterproof pens, and a modest watercolor set. The sketchbook, which is solely for documenting my adventures, helps me recall vivid details about the people, places, and things I encounter — in a more visual, visceral, and emotional way than my straightforward, factual log ever can.

When I open my sketchbook, my mind moves to a new realm of observation. I can focus on just one thing, and I begin to notice details I might have overlooked before. For example, working on a hand-drawn grid, I might spend an entire afternoon creating a penciled, time lapse drawing of my favorite cove near Olympia, each square representing a half-hour interval that captures the water falling with tide. Here comes a rounded boulder as the tide hits the six-foot level. There a channel emerges. Now I can tell you what lurks beneath the surface, should I ever decide to anchor in these shell-covered depths.

A lone heron fishing on a mudflat, ordinarily noted and then passed by, becomes an important element of a sketch at Useless Bay on Whidbey Island. I draw the eroding bluff, observe the angle and texture of a pile of driftwood; even the pattern of the mud becomes interesting. Meanwhile, I wait for a heron to turn and step into the right part of my drawing. I notice its curious legs, how they bend backward, opposite from the way human legs work. Would I have observed that, had I just been floating nearby? I doubt it. Putting pencil to paper makes me a better observer.

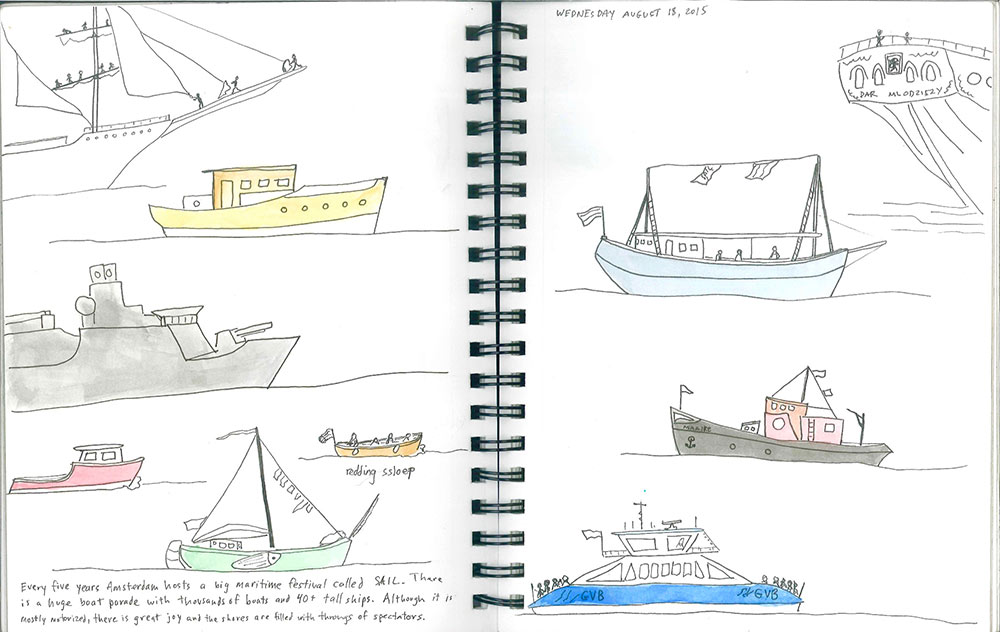

Of course, I draw boats. Sometimes just a silhouette or a simple outline. Other times, I try to include something more complex, like rigging or the fine lines of a wooden boat. I am constantly confounded by the difficulty of correctly capturing the strakes that form a sloop’s elegant curves, getting tighter at the bow. Sometimes I get them right, but often they’re too wavy or imprecise. My sketches aren’t perfect, and sometimes they are incomplete. But that never stops me from trying again. I view each drawing as both a record of where I’ve been, and what I’ve learned about art.

When I share my sketchbook, I sometimes hope to inspire other sailors to start their own. Banish the memory of that mean third grade classmate (or worse, teacher) who said you couldn’t draw. If the same kid had said you couldn’t sail, you’d still be at the dock.

If you want to start drawing, think of your sketchbook as a memory machine. It’s a tool to help you see details, remember stories, maybe even to aid in writing your observations later, about a good anchorage, or a particular hiking trail. A drawing can help you to recall the feeling of a place; it can record the names and portraits of other cruisers you met, or inspire the next color scheme for your craft.

When someone asks where I’ve been on my latest cruise, or what I saw, I’m not shy about pulling out my sketchbook. Maybe they’re not professional caliber, but my drawings reveal a truth about how I see things. I push aside the memory of that mean kid and allow myself to be vulnerable as folks look over my drawings — and interesting conversations always follow.

Unlike my ship’s log, which I feel obligated to write in each day of a cruise, my sketchbook is more personal. If I don’t feel like drawing, I don’t. And if I want to spend an entire afternoon observing a tidepool and drawing an inch-long chiton, I won’t hesitate. If I make a mess of a drawing, unable to accurately capture the contours of a cloud bank, I have no regrets, because I’ve done the best I can. But more often than not, my sketchbook keeps me excited about seeing the world — just the way my boat does.

Bruce Bateau

Bruce Bateau sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Ore. His stories and adventures can be found at www.terrapintales.wordpress.com