A family cruising a classic wooden tug tries to transit a storied Pacific Northwest passage. The author’s childhood remembrance provides a valuable lesson for us all.

My father, Captain Don Leonard, climbed out of the noisy engine room of our 1949 wooden tugboat, Teal, and onto the back deck. He removed his earmuffs, but the engine’s idle was all he could hear. As always on the boat, though, his other senses were attuned to the world around him. He felt the morning sun warming his arms and face as he gazed around the pristine wilderness of Orcas Island’s West Sound. He took a deep fir-and-salt-scented breath while scanning the calm bay’s mirrored image shoreline. Our family was wrapping up a weeklong International Retired Tugboat Association vacation at Pete Whittier’s mansion.

Dad watched the other tug owners bustling around their vessels stowing gear and preparing to depart. His engine sang along with other warming tug engines. They’d all made plans to leave and cruise in and around the San Juan Islands in small groups of two or three while working their way home to various ports around Puget Sound.

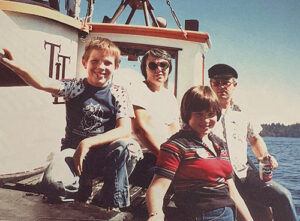

Dad smiled to himself as he reflected on the past week. He and my mother, Linda, and my adolescent brother Charlie and I had gotten to tour Pete’s sprawling home and seven guest houses, swim in the heated swimming pool, admire his personal herd of buffalo, walk on countless old growth forest trails, and catch up late into the night with our favorite tug boating friends. It had been a wonderful week, but it was time to leave.

Mom walked down the side deck to Teal’s stern where Dad stood. She lightly touched his shoulder. He shook his head ever so slightly, bringing himself back to the present. He smiled and turned to her. “The kids are stowing gear on their bunks. The galley is all clean and prepped for travel,” Mom announced over the rumble of the tug’s massive engine.

“Clancy’s warmed up and ready to go,” he declared. Clancy, the endearing name Dad had given the D-343 Caterpillar engine that was Teal’s rumbling beating heart.

“Have you plotted the course you and Paterson will be taking to Deer Harbor?” Mom inquired.

“Yep, it’s definitely a short cut, like Paterson said. We’ll have to really watch our depth and the current. With this outgoing tide, the current will be strong and against us, and Pole Pass is the narrowest pass we’ve ever navigated through,” Dad answered knowingly, feeling a tinge of worry squeeze the oatmeal breakfast in his stomach. Dad was a licensed captain, and his preparations had been rigorous, plotting a course with compass headings on the chart he kept laid out on the pilothouse bench for handy reference. Still, there are unknowns in any new passage and this was in the days before electronic navigation.

Robin Paterson and his wife, Kae, owned the 50-foot wooden British Columbia tug, Winamac, built in 1912. Although Paterson was a seasoned skipper, he did not have his commercial captain’s license. Even so, Dad trusted Paterson because of his years of salty experience in and around Puget Sound. The two families were longtime tug friends and often cruised together.

Charlie and I popped out of the pilothouse. “We’re done,” I informed my parents, all our gear was cleaned up and stowed on their bunks.

“Ok, we’re all set then,” Dad stated. “Charlie, hop over to the Winamac and tell Mr. Paterson we’re ready to go.”

“Okie-dokie!” Happy to help, young Charlie was over Teal’s varnished ironwood caprails and onto the Winamac’s deck before he finished his answer. He bounded back aboard our boat seconds later.

Paterson stuck his head out of his wheelhouse and called out over the roar of the engines, “We’re all set. Let’s cast off our lines. I’ll set Winamac at her usual 6-knot cruising speed and you guys follow us.”

“All righty, we’ll follow you,” Dad answered as courageously as he could, knowing the transit would bring them through unfamiliar waters. Our family had previously visited Deer Harbor in our smaller pleasure boat. Even with past experience of the pleasant Orcas Island port, this would be our first-time arriving by way of Pole Pass.

Full of submerged boulders of all shapes and sizes, Pole Pass was the fastest and shortest route from West Sound to Deer Harbor. The narrow width of Pole Pass (approximately 150 feet wide from shoreline to shoreline, depending on the tide) sat sandwiched between a southwest peninsula of Orcas Island and the largest of the Wasp Islands — Crane Island. Captains shared tales of Pole Pass’s mutinous currents. With an outgoing tide, the saltwater current rushed through the Pole Pass pipeline out of Deer Harbor, as well as Spring Passage and President Channel farther west, forming strong eddies and dangerous whirlpools. Coupled with the current, hidden boulders on both sides made a troublesome opponent even to the most seasoned skipper. Dad knew of a sea shanty about how these savage currents could easily throw a large vessel around, causing difficulties for a captain to maintain control. Even after a successful northbound transit of Pole Pass, there were many small islands and treacherous rocks outside Deer Harbor to maneuver around before getting into safe haven.

Several ways existed to gain access into Deer Harbor, all requiring careful navigation. Some routes were considered safer than others, namely Wasp Passage to the south of Crane Island, especially for larger boats.

The two tug families untied their vessels, waved goodbye to their friends remaining at the dock, and started out on the calm waters of West Sound. Winamac led the way. Paterson never seemed to use charts, a depth sounder, a compass, a tide table, or hardly ever a radio — he just went, sometimes arriving places by the thin, red, bottom paint on his hull. He was known for barreling through anything with endless seafaring good luck. His Winamac was longer and sleeker than Teal, and drew less water, 5 feet to Teal’s 8.5 feet. Paterson could maneuver his old wood vessel into shallower spots, while the shorter, more massive Teal needed more water underneath. In fact, all the living quarters were below the waterline inside Teal.

Soon, Winamac and Teal arrived at the southern entrance to Pole Pass. “With the tide halfway out, only some of the hidden boulders are showing their pretty faces. I can’t see all the ones marked on the chart,” said Dad, pointing out the pilothouse window. He continued, his serious tone filling the wheelhouse. “Linda, I’m going to have to have you follow along in the guide and note the boulders still under water as we enter the pass. The last thing we need is to meet one of them.”

“Will do,” Mom answered, taking the guide in her hands. Rocks concealed underwater are like bombs waiting to shred a passing hull to bits. We all watched from their wheelhouse as Paterson plunged in first. Without slowing down, his boat tilted, rocked, and weaved as he fought the current. Once in, the proud skipper appeared to have bitten off more than he could chew, but he decided to continue, swerving and zigzagging, his tug tilting to port and starboard all the way.

“Paterson will never admit it, but I’ll bet he’s holding onto his wheel with both hands,” Dad said, thinking aloud.

Just then, as if to confirm Dad’s statement, Paterson radioed, “Winamac to Teal. The current’s a wild beast. It’s doable though. Just keep your vessel dead center as best you can.”

Surprised at Paterson’s unusual use of his radio, Dad gulped and answered, “Teal to Winamac. Copy that. Will do.”

Teal was ready to go next, in line behind Winamac. Dad jockeyed his trusty tug into position, already fighting the current to stay in the deepest part of the channel, and headed forward against the swift water.

Suddenly, up ahead, a southbound sailboat entered the narrow pass behind Paterson and began gliding out downstream. Though perfectly situated, Dad had no choice but to wait for the outcoming sailboat and put his vessel in neutral. Another pleasure boat quickly cut in directly behind the sailboat. Dad had to continue to fight the current outside the pass, constantly resituating his stout tug while he waited.

Finally, it was our turn. I stood in the starboard side of the pilothouse, keeping one eye on the depth sounder mounted above me and the other eye on the challenge that lay ahead.

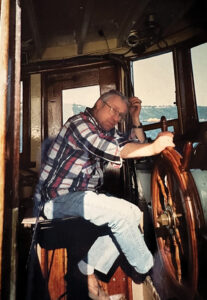

Dad maneuvered back into the center opening of Pole Pass. All was clear. “I’m going downstairs to take a nap,” Charlie announced, too nervous to watch. Dad eased the throttle forward, and Clancy obeyed. A battle ensued. Whirlpools collecting debris swirled on either side of Teal. He leaned in and fought at the helm with all his might, turning the large, wooden steering wheel left and right with his full body. Captain and vessel were joined as one.

“Move to port, the chart shows a boulder off to starboard,” Mom called. Wordlessly, Dad redirected Teal.

Suddenly the readings on the depth sounder started coming up. And up. And up. “We have 20. No… 18. No… now 12 feet under us!” My voice cracked.

“It’s getting too shallow too fast!” Mom tensely announced.

Glancing at the depth sounder while eyeing the snarling water ahead of them, Dad made a split decision. “To heck with this!” Dad bellowed.

It was just too risky. No way was he going to let his family nor his beloved tug become a part of Pole Pass’s lore. He cut the throttle to neutral and spun the substantial steering wheel hard over to port, turning the mammoth rudder beneath the stern as sharply as he could.

The torrent instantly released its grip and blew the vessel straight out of danger. My family breathed relief as we shot out of Pole Pass, motoring south toward Wasp Passage. My parents exchanged a knowing look, and Dad said, “We’re not following in someone else’s wake today.”

Then he turned to me, smiling, “Sometimes, Sis, you gotta make your own path in life. Today we did just that.” I could only give a shaky nod.

We puttered all the way around small, fir-blanketed Crane Island. There were still navigational hazards, but there was deeper water and less current. Teal entered Deer Harbor, safely rejoining Winamac.

The intense events of the day reinforced for my father that a captain must rely on his or her own judgements, calculations, skill, knowledge, know-how, and confidence. The others can keep their opinions and their luck.

Lisa Nickel grew up boating out of Tacoma on the tugboat Teal and believes there was no better way to grow up. Today, she is happiest when spending time with her husband, daughter, and family. She is working on a middle grade novel about a girl on a tugboat, and is co-authoring an Arcadia Publishing “Images of America” book on the historic Olympia tug, Sand Man, with Chuck Fowler.