One Change, So Many Options

From the March issue or 48° North, photos courtesy of Drew Malcolm

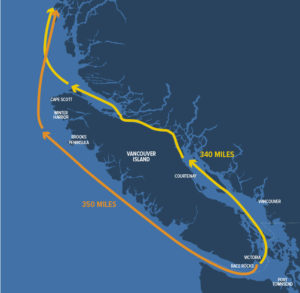

When Race to Alaska (R2AK) teams hoist their sails outside of Victoria Harbour on June 11, 2020, some of them will be faced with a supremely difficult decision: Go east up the inside of Vancouver Island towards winding channels and gnarly currents. Or, go west out of the unpredictable Strait of Juan de Fuca into the mighty Pacific Ocean and hope for the best enroute to Bella Bella.

The removal of Seymour Narrows as a mark on the race course is a significant change for the next iteration of the Race to Alaska, one that casual fans and bonafide tracker junkies alike will be following with excitement. I know I will. R2AK 2020 is going to be like nothing we’ve ever seen.

Full of twists and turns, the previous five versions of the race captivated fans and had them holding their collective breath while racers endured unruly currents, fluky to heavy winds, driving rains, gear failures, incredible human efforts, and a large dose of the unknown on their way to Ketchikan. To be sure, on a race course that spans 750 miles through the Inside Passage, questions abound. How will teams handle all the variables of the watery wilderness? Will they be forced to stop? Will their boats and gear hold up? What routes will they take? Now, with one less rule, the questions are broader than ever before.

THE BIG CHANGE

The removal of Seymour Narrows as a mandatory race waypoint was met with a chorus of “Ooo” and “ahh” during the Blazer Party announcement at the 2019 Wooden Boat Festival in Port Townsend. And, at first glance, fans and racers alike wondered, “Why the change?”

For the R2AK braintrust, the removal of the waypoint was a two pronged decision: First, “In a race with few rules, we simply wanted to see if we could eliminate one more of them,” quipped Race Boss Daniel Evans. And, second: “After five years of running the race, we felt like the puzzle of going through Seymour Narrows had largely been solved. We wanted to give racers more options, more puzzles to play with.”

If racers wanted more puzzles to solve, they’ll certainly get it with this rule change. And when the news broke, most would-be or armchair R2AK racers shifted their focus to the outside of Vancouver Island. Rightly so. But eliminating the checkpoint at Seymour doesn’t just make the outside possible, it also opens up several puzzling routes around the Narrows that will likely intrigue navigators on every team.

Having raced in the 2018 R2AK aboard Team Wild Card, sailed in the 2015 Van Isle 360, and cruised my own boat up and down the Inside Passage and north and south on the outside of Vancouver Island, here’s my breakdown on going outside versus staying inside.

THE OUTSIDE PUZZLE

Before racers begin their journey out into the Pacific Ocean, they must get approval from the Race Boss. Preparation and experience are paramount. Teams have to declare on their application if they are thinking about going outside and then their experience and choice of vessel is vetted by race officials. If approved, they’ll then have to pass a rigorous safety inspection that is based on a combination of US Sailing’s Safety Equipment Requirements (SER) for coastal and ocean races, the Swiftsure Race SER, and input from the Canadian Coast Guard.

Assuming they’ve completed all that, here’s what racers will face when they make the decision to turn west and piece together the outside puzzle. From Victoria Harbour, it’s roughly 350 miles to the only checkpoint at Bella Bella. Over that stretch of water, there are numerous obstacles to contend with, the first of which is Race Rocks. A collection of rocks, reefs and small islands, Race Rocks is 8 miles from Victoria Harbour and, for a motorless vessel traveling westward, it is best left to starboard or transited in prime current conditions at slack water or during an ebb. Unfortunately for racers, the current through Race Rocks on June 11 is going to be a major obstacle to heading outside: the flood starts at roughly 2pm (the race starts at noon). They’ll have just two hours to get through on the last of the ebb; and for almost all R2AK boats, they’ll spend at least half of that working their way out of the harbor under human power.

From Race Rocks the full brunt of the Pacific is ahead, but teams will have to tackle 50 miles of Juan de Fuca madness that will likely be light wind or a building afternoon westerly. Tacking back and forth along the Vancouver Island coast against the building flood, if the wind does kick up, it’s going to be a tough first six hours. Then, towards the end of that 50-mile stretch, the tide is going to turn from a flood to an ebb and progress might get a bit easier as nighttime descends.

Realistically, the first portion of the outside route might feel a bit like a Switftsure started four hours later. Even the fastest boats need six hours or more to make the westward transit to the mouth of the Pacific, meaning the R2AK transition from Strait to ocean will likely happen around or after nightfall. Anyone who has slatted around all night with the knotmeter reading 0.0 near Swiftsure Bank knows that the patch of water just west of the funnel of Juan de Fuca is seldom where overnight heroes are made. Yet, you never know…

What’s next is 200 miles of rugged, unforgiving coastline to notorious Cape Scott at the northwest corner of the island. That 200 miles is going to be a potential slog, especially if the typical northwesterly breezes of June come up in the afternoon. At this point, root for southerlies and westerlies if your favorite team goes outside.

Though rugged, there are places for racers to stop on the outside of Vancouver Island if needed. From south to north, Barkley Sound, Clayoquot Sound, Nootka Sound, Kyuquot Sound, and Quatsino Sound all offer protection, but it can be a long way in and out to the ocean, costing teams precious time and miles. Another possible stop can come in the Bunsby Islands before rounding the Brooks Peninsula, which has to be taken with care.

The Brooks Peninsula is a mountainous, rectangle shaped monolith that juts nine miles out into the ocean. Wind accelerates around its corners, which means that in a strong northwesterly flow, racers could easily be fighting 30-knots and large seas. Again, hope for a southerly.

When teams have successfully rounded Brooks, Cape Scott looms 50 miles to the north. At the confluence of the Pacfic Ocean and Hecate Strait, the waters around the cape can be a nasty combination of current and wind. And if a strong northerly is funneling down the strait between the cape and nearby Scott Island to the west, they’ll want to be anywhere but there.

Pass Cape Scott, and the stretch to Bella Bella will be in their sights—85 miles to the north. This section of the race course could favor outside versus inside boats if there is a strong northwesterly wind blowing. Those coming from Queen Charlotte Sound will likely be beating, but those coming from Cape Scott may be able to fetch Bella Bella on a long port tack. This is also where it could get fun for tracker junkies, as there is potential to watch competitors race against one another for the first time since Victoria Harbour, some 300-miles distant.

It has to be said here that going outside will be largely dependent on weather. If a good-to-great forecast on the ocean pops up, it’s likely teams will go for it. I would. But if teams go outside and are forced to tack even a portion of the length of the island from Victoria to Cape Scott, that 265-mile stretch could easily turn into 350 or more. And that’s not even accounting for the possibility of going way out. The shortest distance is a track that loosely follows Vancouver Island’s west coast, but the right weather set-up could call for a big dig west as the first move in the ocean. This gamble could remove some of the geographic influences (both positive and negative), reduce maneuvers, and potentially give access to different weather systems and sea states. For any of those outside routes, it’s difficult to say how effective human power systems will be if the breeze goes to nothing and pedalers or rowers are left to contend with residual ocean swell.

On the bright side, they won’t be dealing with the puzzle of fickle winds and strong currents on the inside that could force delays in forward progress.

THE INSIDE PUZZLE

Possibly more intriguing than going outside, the teams that choose to stay inside now have an abundance of possibilities open to them with the removal of Seymour Narrows as a checkpoint. Victoria Harbour to Bella Bella via Seymour Narrows is 340 miles, 10 fewer than going outside. However, the miles between the Gulf Islands and Johnstone Strait are going to present opportunities for navigators that didn’t exist before.

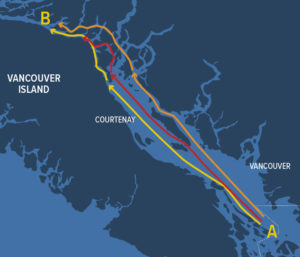

Hypothetically, starting at a waypoint (A) outside of Active Pass in the Strait of Georgia and ending at a waypoint (B) in Johnstone Strait near the west end of Hardwicke Island, there will be several potential routes that might split the fleet, and make exciting new experiences for racers and their followers at home. (Note: All distances are approximate.)

The traditional race route from A to B through Seymour Narrows is 150-miles, and the all-important timing of transiting the narrows is crucial. Take it away, though, and options open up to the east in order to skip it.

The first, most obvious, route change is to hop around Seymour Narrows by going east of Quadra Island past the Octopus Islands. Compared to the traditional route, this will take teams 156-miles from point A to B. It will also introduce the need to transit Surge Narrows and the Upper and Lower rapids at Okisollo Channel, which, if timed right, could provide a significant boost. If timed wrong, there are several good places to stop close to the rapids.

Another, even more easterly option teams have is to leave from point A and sail, row, and pedal towards the east side of the Strait of Georgia. From there, they can leave Texada Island to port and squeeze through Desolation Sound by leaving Cortes Island to port and then head towards Yuculta and Dent rapids. After the rapids, transiting to the north of East Thurlow Island, through Green Point Rapids, and then on to point B will be a total of 157-miles. There is certainly a lot that goes into that route, and I can’t predict every wind and current scenario, but it is a possibility.

Yet another option would be to combine going east towards Texada with the route through Okisollo Channel. It’s a virtually equal distance of 156-miles to leave Texada to either port or starboard and, in my personal experience, there tends to be more wind on this side of the Strait than up against the Vancouver Island side. For instance, in 2018, Team Wild Card went between Texada and Lasqueti islands and shot north into the front of the pack with wind while others languished in adverse current and no wind just miles away to the west. We solved that part of the puzzle, at least for that year.

The route through Seymour still represents the most direct route, but the prospect of six hours at anchor waiting for the gate to open may well incite numerous rolls of the dice on those eastward routes. The addition of the gate possibly opening earlier on the inside route adds to the intrigue.

My personal history and intimate perspective makes me envious and eager for my fellow navigators who are currently pouring over charts and planning their adventure north. As in any race, there’s no perfect plan, because the puzzle pieces won’t take shape until timing, conditions, and competition variables materialize in the moment.

Race to Alaska has been thrown wide open, and literally anything is possible now. I, for one, will be glued to my tracker watching this giant new puzzle being solved before my eyes.

Andy Cross

Andy Cross is the editor of 48° North. After years cruising the Pacific Northwest and Alaska with his family aboard their Grand Soleil 39, Yahtzee, they sailed south and are currently in the Caribbean Sea. You can follow their adventures at SailingYahtzee.com.